Duane Owen execution: Did Karen Slattery's younger sister find a rainbow in killer's death?

RAIFORD — Rain had come again to Raiford.

Thunderstorms swept across this north Central Florida town, which is defined by the sprawling Florida State Prison campus that takes up both sides of State Road 16 as much as by anything else.

Thursday's wind and rain, the deep rumble of thunder, it was all cinematic, clichéd even. For a man was going to be executed on this day, his last minutes on Earth truncated by repeated denials of his frantic legal appeals.

Even as others got up for work, went about their day, 62-year-old Duane Owen was writing out his last words, eating his last meal, waiting for the moment when he would be escorted into a small white room, a room he'd never leave alive.

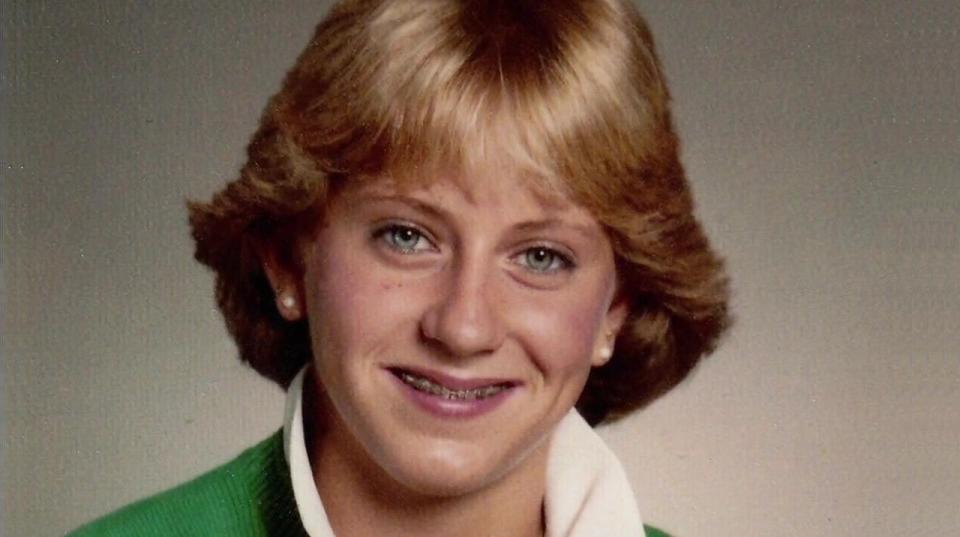

Would big sister Karen Slattery be watching?

"I have transcended space and time," he wrote. "I have seen the visions of the Crow."

Debbi Johnson saw hope in the rain. She wanted a rainbow.

Wouldn't that be fitting — to have some beauty stretched out over this wretched day?

Johnson's mother had told her rainbows were a sign that Johnson's sister was still with them, that 14-year-old Karen Slattery wasn't really gone forever.

Slattery's 1984 murder in Delray Beach and, two months later, the Boca Raton killing of 38-year-old Georgianna Worden, a single mother of two, were so ghastly they'd blanch a horror writer.

It would be too much — a teenage babysitter stabbed 18 times, raped, a 38-year old mother raped and bludgeoned with a hammer five times, somehow surviving 30 minutes to an hour after the first blows. Who could stomach that? Who could process such ghoulish violence?

True Crime: Duane Owen murders babysitter Karen Slattery, 14, and woman, 38, as children slept

From those March and May days in 1984, when Slattery and Worden were killed, until that rainy Thursday, their families were left with just that task. They had to move on, to piece lives together through the terrible wreckage Owen wrought.

Slattery's murder killed something else, too.

"I was no longer a child at that point in time," said Johnson, who was 10 when her sister was killed. "No kid should have to go through that. It's just ... kids are supposed to be young and frolic and make stupid mistakes and learn from them, and I wasn't given that option."

Nearly four decades would pass from the murders to Thursday in Raiford.

"Thirty-nine years is too long, way too long," Johnson said. "We know who did it. We know who committed all of these crimes. There was no reason that it needed to take this long."

Again and again, Owen's attorneys would point to his catastrophic childhood, which saw his mother, an alcoholic, die when he was 11 and his father die two years later by suicide. They'd note his childhood drug and alcohol abuse, his gender dysphoria, a condition where a person's biological sex does not match their gender identity.

Owen's attorneys would write brief after brief, pointing to evaluations showing him to suffer from schizophrenia, psychotic delusions and dementia.

More: Duane Owen executed in killings of babysitter, mom. What Karen Slattery's sister said

Georgianna Worden's parents wouldn't live for 39 years

Courts would take a dim view of those arguments. The years would churn on, and Owen would move closer to that small, white room, the one with the gurney and the IV of poisons.

Worden's parents would grow old and die, wounded in unspeakable ways.

"Georgianna should not be dead," her father had told a court in 1986, pleading for Owen's execution. "Georgianna had her right to live, yet it was taken away by Duane Owen."

Johnson would grow up and turn to the only institution that could grasp what Owen had forced upon her and her family: law enforcement.

She's a deputy sheriff in Monroe County now. Only she wasn't just that on Thursday. She was a little sister, pausing and crying a little as she tried to relay just how much Owen took, how much beauty left the world with her big sister.

"Karen lives on in her community, her friends, her family, and, most importantly, her legacy," Johnson said.

Johnson would be among 34 people who sat on the other side of a glass partition as Owen was brought to that white room at 6 p.m., where his execution was to take place.

In the long minutes before 6, none of the 34 spoke. Instead, they stared straight ahead at the glass partition, waiting for a screen to be lifted. Because of that screen, they'd only see themselves as they stared.

Loud cracks of lightning and bursts of thunder interrupted the silence. Outside, the rain continued.

When the screen lifted, a digital clock on the wall read 6 p.m. Three people stood in the white room as Owen lay strapped to the gurney, a white sheet covering nearly all of his body. All that was visible of him was his head and his left arm, which was pinned down with leather straps. An IV snaked to the crook of his left arm, opposite his elbow.

Johnson dabbed her eye with a tissue.

A large man with a Secret Service build picked up a phone and spoke. His words were not broadcast to those watching.

Then, he turned to Owen, asking if he had any last words. Even before the man finished asking the question, Owen offered a sharp, terse retort: "No."

For subscribers: 3 former South Florida journalists covered executions. What they saw, in their own words.

Duane Owen closed his eyes to the people watching

Owen kept his eyes closed, not looking at those in the room nor at the people on the other side of the glass partition.

At 6:02 p.m., his chest rose and fell rapidly. A minute later, his upper body jerked and his shoulders twitched.

Florida Department of Corrections protocol calls for the condemned to be sedated before the lethal cocktail is administered. Owen's body was reacting to something, the sedative or the cocktail. It wasn't clear.

At 6:05 p.m., the big man grabbed Owen by the shoulders and shook him, hard, before lifting an eyelid. That, too, is part of the protocol.

Owen said nothing, though his jaw appear to slacken and his mouth opened. The man turned away and stood, ramrod straight, holding one hand over another.

The big man on the phone in the execution chamber

There was more twitching before Owen's body stilled. His lips and face had taken on a grayish pallor.

At 6:13 p.m., a woman in a white lab coat came in to check Owen's vital signs. She used a stethoscope to listen and then lifted an eyelid and flashed a light into Owen's eye.

The woman left the room, and the big man got on the phone again.

He turned to those on other side of the glass partition.

"The sentence of the state of Florida versus Duane Owen was carried out at 6:14 p.m.," he said.

The screen lowered, and family and friends of the victims left the room, followed by members of the media.

Outside, it was raining harder, and evening was coming on.

More: Richard Burk, the 'hanging judge' who sentenced Duane Owen

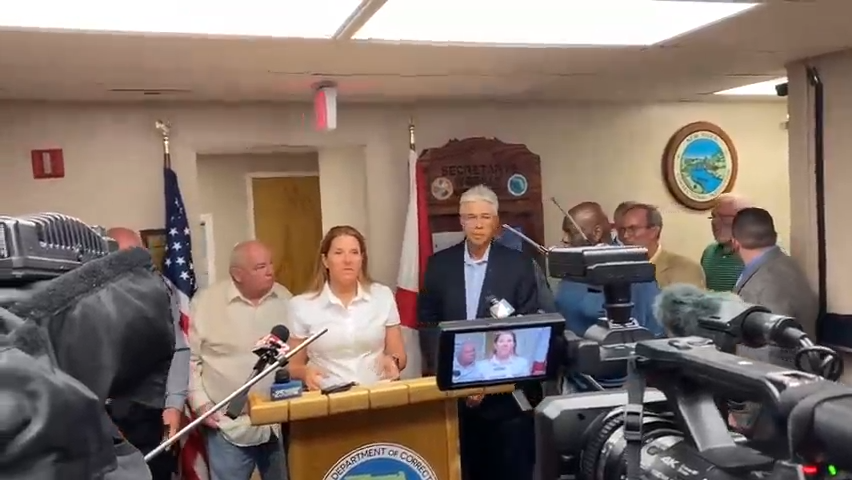

Johnson, backed by many of those who had witnessed the execution, addressed the media in a small administrative building across the road from the part of the complex where Owen was executed. The building's door was open, and the rain fell loudly on its concrete steps.

"Thirty-nine years in this process is finally over," Johnson said. "I entered as a young child, naïve to the bad in the world, only to emerge at the very end as an adult with too much personal knowledge as how bad things happen to good people without provocation."

Other than a corrections spokeswoman, who said the execution was carried out "without incident," only Johnson spoke, alone in giving voice to the pain of those left in the wake of the murders.

"Closure may be a myth, but justice isn't," Johnson said.

She noted the solemnity of the moments before Owen was put to death.

"It felt like a lifetime," she said. "I've never been in a room with so many people where it's been so quiet for that amount of time. And, when the curtain went up, it was extremely emotional because this was it. It was finally going to be done within a matter of minutes, too many minutes. Too many."

Johnson thanked fellow law enforcement and the victim's advocates, who advised her and others on what they should expect to see when Owen was put to death.

There was one thing for which she wasn't quite prepared, the jarring juxtaposition between how Owen died and the way his victims died.

"He died with dignity, and, unfortunately, his victims did not," Johnson said.

Owen's last words were distributed to reporters on a folded white piece of paper.

"I have transcended space and time," he had written. "I have seen the visions of the Crow. My energy and particles will transform ad infinitum, I will live on. I am Tula. 13"

There would be no explanation of what the words meant. Were they the ramblings of a madman? Were they final stabs at those he did not kill?

"I will live on..."

By the time Johnson had finished speaking, it was clear the sun would not emerge.

There would be no rainbow.

"I was really hoping I was going to see a rainbow," Johnson said, fighting back tears. "Because that's what my mom always said: Whenever you see a rainbow, that's Karen smiling down on us. And, I'm kinda disappointed. There's no rainbow. But the rain will stop, and I'm sure I'll see it. She'll come through in her own way."

Wayne Washington is a journalist covering West Palm Beach, Riviera Beach and race relations at The Palm Beach Post. You can reach him at wwashington@pbpost.com. Help support our work; subscribe today.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: Duane Owen's execution: Karen Slattery's sister after killer executed