Duplicate drafts, ‘Daffy Duck’ tests: How NC caused nationwide death data delays

North Carolina officials say they’ve corrected problems with state death records that have for months delayed a national accounting of how people in America die.

But there remains no timeline for public release of the U.S. data, which health experts say is critical to understanding everything from pregnancy-related death rates to lives lost to the country’s opioid epidemic.

After the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention quietly postponed the nationwide release of 2022 finalized mortality data late last year, The News & Observer revealed in January that missing death records from North Carolina were responsible.

Emails obtained by The N&O this month showed repeated concerns about the state’s data throughout 2023, culminating in a delay that would “likely have cascading impacts,” CDC officials said.

The correspondence sheds new light on why the state’s transition to fully electronic death reporting in September 2022 sparked concerns about the missing records — and how state officials solved the problem.

North Carolina officials ultimately concluded their data was missing only about 300 records, which they submitted to the CDC by mid-February. That’s just a small fraction of the 110,000 or so deaths in North Carolina annually.

But state officials originally feared the problem was much worse, records show.

CDC: Delay would bring ‘cascading impacts’

First piloted in the fall of 2020, the phased transition to have funeral directors and medical providers submit electronic death certificates was a long time coming for North Carolina, one of only three states that still filed death reports on paper.

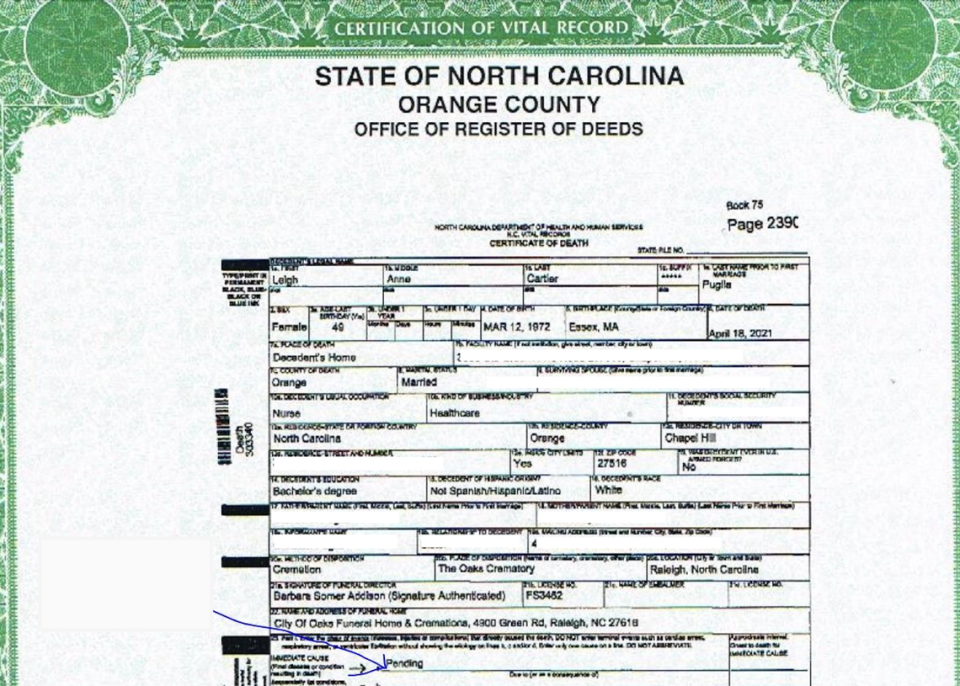

Done right, electronic reporting speeds up the often bureaucratic process of filing these documents, critical for both families mourning lost loved ones and researchers monitoring the health of the nation.

But in 2023, the state’s death data for the previous calendar year wasn’t adding up.

In late August, emails show, state health officials alerted the CDC to about 1,700 missing records that had to be submitted to the federal agency after a key deadline.

Terra Ankrah, interim director of the N.C. Office of Vital Records, attributed the problem to a “learning curve” for funeral directors and medical providers, who through most of 2022 could still report deaths on paper, electronically or both. And state lawmakers had delayed the transition deadline from May to September, she said, creating more inconsistencies.

“There were some records that just didn’t make it into the system because they were in paper format, and there was a little bit of confusion about whether they were electronic or paper,” Ankrah told The N&O Friday.

In mid-October, vital records staff found more evidence of problems.

DHHS statisticians discovered an abnormally low infant mortality rate for 2022 — a number they feared was too good to be true, emails show.

“We have to make sure we have a handle on this before releasing any numbers, as an all-time low infant mortality rate will definitely be news and it seems like that number isn’t real,” Robert Lee, a supervisor at the State Center for Health Statistics, wrote to DHHS colleagues on Oct. 19.

On Nov. 30, Ankrah raised the problem to her counterparts at the CDC: There were many more deaths the state had not yet reported.

A week later, the CDC had heard enough.

“After some internal deliberations we have decided to delay release of the national final until we have the missing NC records,” Paul Sutton, deputy director of the CDC’s Division of Vital Statistics, wrote in an email to Ankrah on Dec. 6. “This is a significant decision and will likely have cascading impacts, but we believe it’s important to insure the final data file is as complete and accurate as possible.”

Incomplete drafts responsible for delay

One of the primary causes of the problem, Ankrah said, was a backlog of unsubmitted “draft” entries that funeral directors and medical providers added to the system. In many cases, she said, filers would start a draft of a death certificate, leave it unfinished, then start and complete a new entry later.

Emails show DHHS staff initially found more than 10,000 of those drafts in the system. Ankrah said in an interview they were quickly able to whittle down that number to just over 4,000 by removing duplicates and other obviously invalid entries used to learn the system.

“We were able to, with very just basic matching, make a quick determination that these were test records,” Ankrah said. “So if you saw a death record that said ‘Daffy Duck,’ you kind of know someone was just trying to test the system.”

What remained, vital statistics staff soon learned, were thousands of incomplete drafts that duplicated deaths already complete in the system.

“The stakeholder eventually registered the death,” Ankrah said. “They just didn’t do it from the draft they started previously.”

Some unsubmitted drafts contained enough information for vital records staff to match to an existing death record. For others, they had to contact funeral homes and medical providers for more details.

That process took time, Ankrah said, especially for a vital records office facing a 40% vacancy rate — and the launch of an electronic birth registration system in January.

Since she first alerted the CDC to the issue in late November, Ankrah said DHHS staff found 318 records actually missing from the state’s data, which they’ve now submitted as part of the final death file.

Federal officials signed off the state’s resubmitted records Feb. 16, according to CDC spokesperson Christy Hagen. Federal analysts there are currently working on cleaning up the national file for public release, she said.

In the meantime, public health and population researchers must make do with provisional information on deaths across the country, which although more recent may change as records are finalized.

Ankrah said she’s not concerned that the next batch of death data for 2023 — due to the CDC annually in May — will see the same problems. Improvements to the system will allow the agency to better understand where errors originate and target counties or even funeral homes for additional training, she said.

But the electronic system will also mean more routine follow ups from the state vital records office, which Ankrah said is standard practice in other states.

“When you had a paper world, people didn’t mail you drafts, right?” Ankrah said. “There’s a learning curve for both the stakeholders and our staff.”