Dutch society has 'failed to examine' slavery's role in Golden Age, says director of national museum

The Netherlands' national museum yesterday unveiled details of an exhibition charting for the first time how slavery helped forge the Dutch ‘Golden Age’.

The director of Amsterdam's Rijksmuseum, Taco Dibbits, said that the country's slave-dealing past had been "insufficiently examined", adding that Black Live Matter protests had injected urgency into the project.

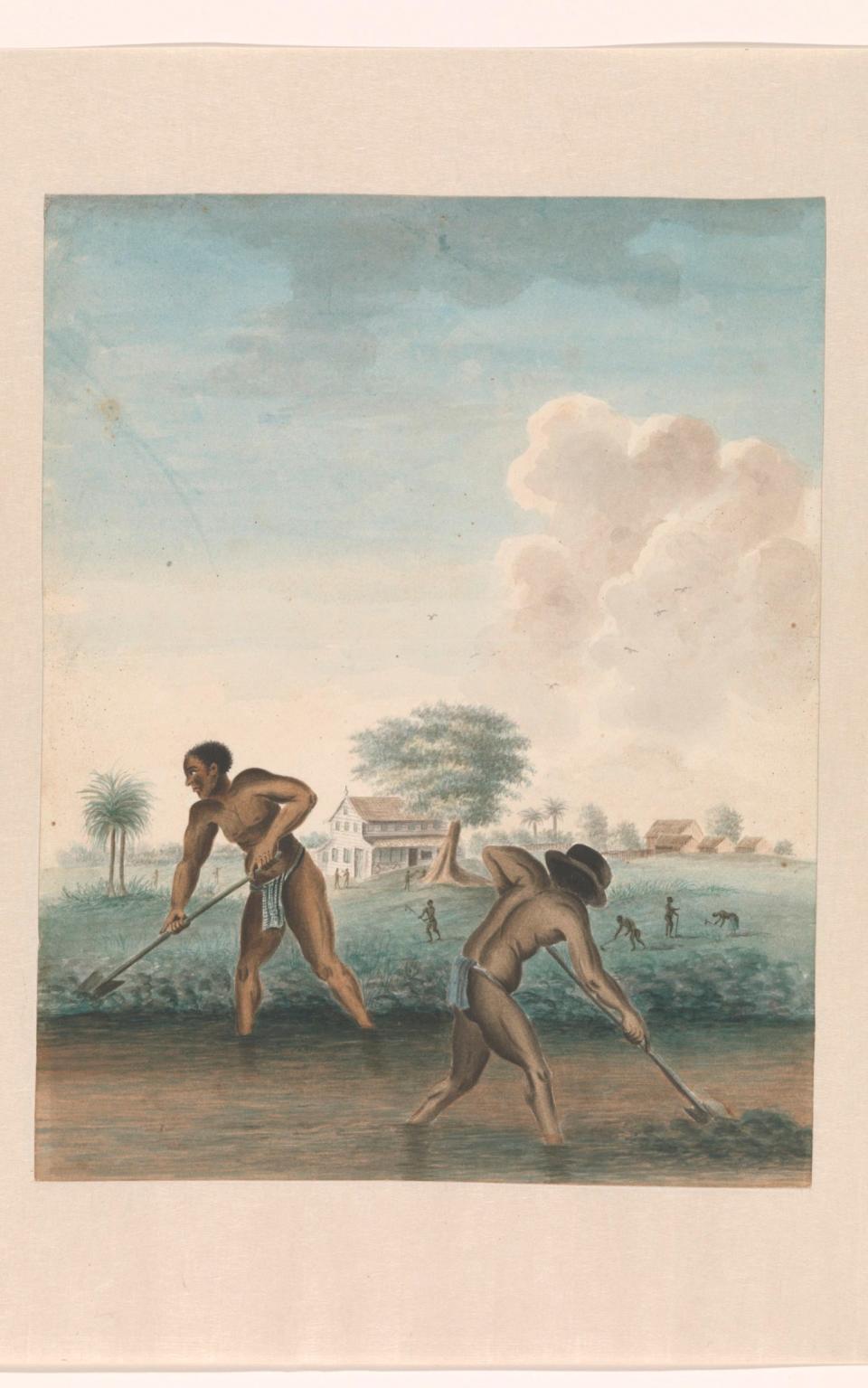

The exhibition, which begins in February, will feature 10 rooms with 10 stories of individuals who were connected with slavery, from slaves in sugar plantations who broke free, to an African servant in the Netherlands and an Amsterdam sugar magnate. Among the 140 artefacts will be a wooden contraption used to manacle slaves so that they could not escape at night, as well as a celebrated Rembrandt double portrait of the wealthy couple Maerten Soolmans and wife Oopjen Coppit.

“Slavery was an essential component of the colonial period in the Netherlands and many generations have suffered unimaginable injustice as a result,” said Mr Dibbits.

“The past has been insufficiently examined in the national history of the Netherlands, including at the Rijksmuseum. We felt that slavery is of great importance to our society today [and] Black Lives Matters shows the urgency that this subject is addressed.”

The Dutch Golden Age, roughly spanning from 1581 to 1672, turned the Netherlands into an artistic, naval and economic powerhouse. But much of the success was underpinned by slavery.

The Dutch were one of the last western nations to abolish slavery in 1863, three decades after the British had done so, and earlier this year prime minister Mark Rutte said it would still be too ‘polarising’ for the government to apologise for its slaving past. Valika Smeulders, head of history at the Rijksmuseum, said they wanted to overcome some people’s national pride or resistance to these facts by using personal stories.

“I’ve been working on slavery history for years and to do this for the national museum of the Netherlands was a beautiful challenge,” she said. “How do you do this for an entire country where people don’t necessarily agree on how you deal with this history?” Dibbits also called for better teaching on slavery in schools, and said that the museum supports recent moves to return looted colonial art.

“This show on colonial slavery is not isolated: this is the beginning,” he said. “We have been doing research into our collection for many years on slavery and we will show the relation between objects in the collection of the Rijksmuseum and slavery with many more initiatives.

“The Rijksmuseum should be a house for everybody, and by telling a completer history of the Netherland we also aim to have a completer public.

Tom van der Molen, curator at the Amsterdam museum, praised the exhibition but said that the exhibition was likely to be controversial. "This subject touches a feeling of national identity and people’s own identities, and people don’t like it when they want to be proud of these," he said.