The dying man was sent back to his cell. A look at how COVID-19 kills Florida prisoners

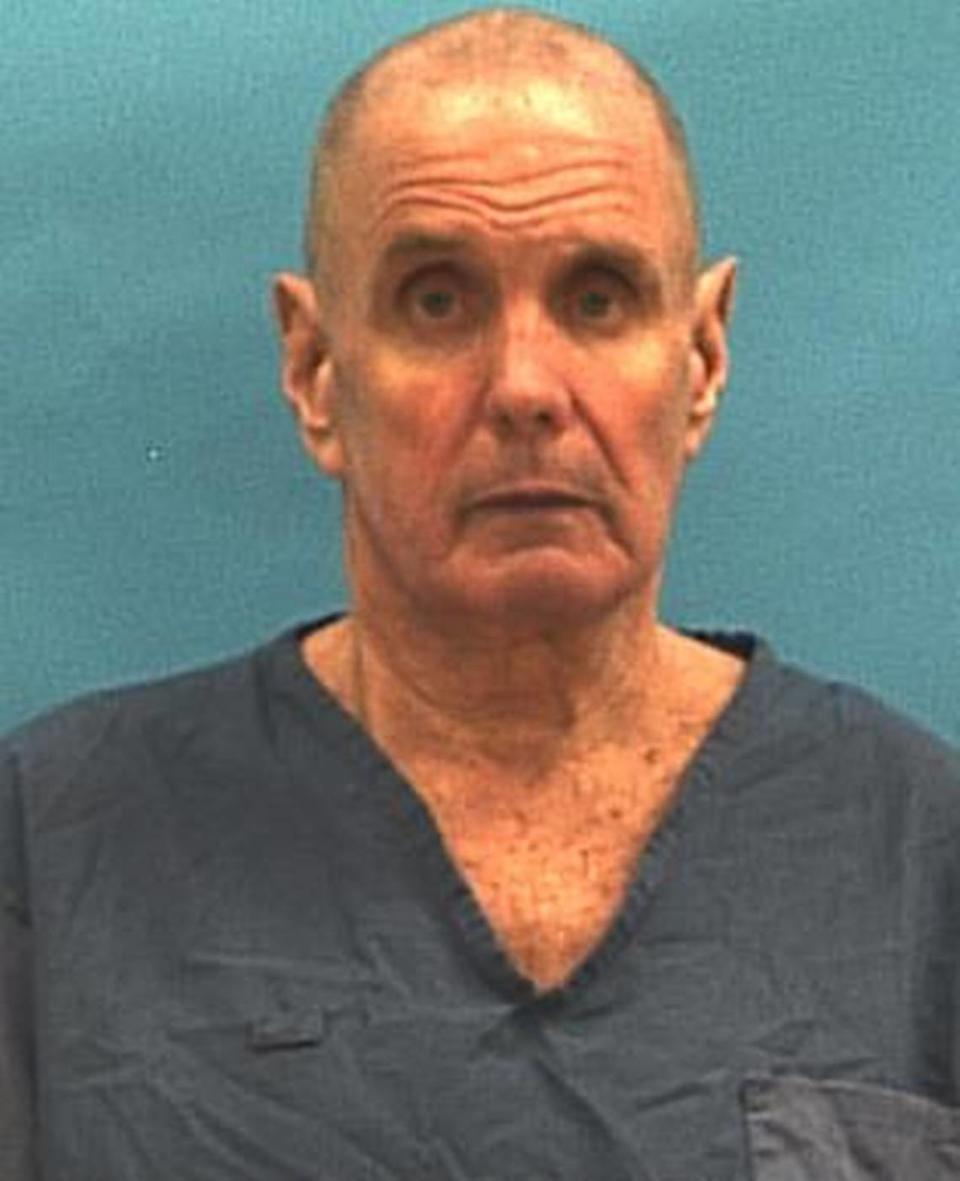

On April 5, when Florida’s positive coronavirus cases were one-sixteenth the number they are today, 69-year-old Jeffrey Sand went to the infirmary at Blackwater River Correctional Facility, a privately managed state prison near Pensacola.

He complained of shortness of breath — and of a cough and diarrhea. Four days later, he was put back in his cell. He died there that same day, found sprawled on the floor of his cell, next to the door. The medical examiner says it was COVID-19, the first such death in the state prison system — but far from the last.

Until Monday, all the public knew was his name, and only because reporters confirmed it with the medical examiner in Santa Rosa County shortly after. No one knew that he was sent back to his cell by the infirmary while apparently on the verge of death. Sand was one of 2,443 inmates in the state who tested positive for COVID-19 and one of 25 who died.

Department of Corrections officials divulge precious little information about the circumstances under which inmates die, making it nearly impossible to determine whether inmates received adequate care. There were 361 such deaths in the first 10 months of the just completed fiscal year, and the only information the department shares on its mortality database is name, prison, date of death, cause (homicide, suicide, natural...) and status of investigation.

The medical examiner data, released after the Herald and other news organizations threatened a public records lawsuit, fills in some of the gaps. Although the COVID-19 victims are nameless in the ME records, short narratives and other data relating to each death provide clues that allow at least some of the victims to be identified as inmates.

All names used in this article were confirmed by the Miami Herald with medical examiners, family members or inmate advocates.

The medical examiner records detail a 53-year-old at Liberty Correctional Institution who had a fever, dry cough, shortness of breath and body aches for three days before being taken to the Calhoun Liberty Emergency Room, where he tested positive for coronavirus and died shortly after. Also revealed: How a 68-year-old inmate at Sumter Correctional Institution who was put into medical isolation with fever and shortness of breath died of COVID-19 four days later.

In another case, a 67-year-old inmate at Union Correctional Institution was taken to Memorial Hospital in Jacksonville with stomach pain. There, he suffered kidney failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome and went into septic shock. He was intubated and later transferred to hospice, where he died.

The medical examiner records provided by FDLE account for only 16 of the state’s 25 COVID-related deaths in prison, which corrections spokeswoman Michelle Glady says is likely a result of a lag in reports from medical examiners’ offices. The Department of Corrections reports deaths of inmates who have tested positive for COVID-19, not inmate deaths ruled COVID-19-related by medical examiners.

It’s also unclear whether medical examiners may be omitting the prison connection in their notes. Details provided by medical examiners vary greatly from district to district.

“FDC is releasing information on deaths of inmates who tested positive for COVID-19, regardless of the cause of death,” Glady told the Miami Herald in an email. “The district medical examiner is responsible for determining the cause of death for any person who dies in a prison, and that determination is releasable by the medical examiner.”

The inmate deaths reported by the medical examiner trend older, with an average age of 61. The youngest inmate to die of COVID-19 was 41-year-old Tyra Williams, a prisoner at Homestead Correctional Institution. Williams, who died June 25, was one of two women to die of COVID-19 in prison so far.

Florida’s aging prison population, like the state as a whole, is threatened by the highly contagious virus, which has had an outsized impact on older people. There are currently about 23,000 Florida inmates over 50, a segment of the prison population that has increased by 12.5% over the past five years as the overall prison population has shrunk. Their care is expensive, even when there isn’t a pandemic, because many abused drugs before prison and they tend to be in poor health. Prison healthcare, not known for its excellence, can make matters worse.

In 2018, elderly inmates — in the prison environment, “elderly” equates to all those 50 and over — accounted for half of all hospital admissions, despite making up just 24.2% of the population.

During the 2020 legislative session, lawmakers proposed bills to help streamline the process of releasing sick or elderly inmates — populations most at risk of dying from the disease. Both bills went nowhere. St. Petersburg Republican Sen. Jeff Brandes put forward one bill to create a streamlined process for the release of inmates with terminal or debilitating illnesses, and another would have established a conditional release program for inmates over 65 who had served at least 85% of their sentence.

In some states, frail or older inmates are being released as a solution to curbing the spread among the most susceptible population, but Florida is not among them. Currently, some inmates deemed “terminally ill” or “permanently incapacitated” and not a danger to themselves or others can be referred by the Department of Corrections to have their cases heard by the three-person Florida Commission on Offender Review.

When asked about the process earlier this year, FDC Secretary Mark Inch said in a statement that releasing an inmate is a “complex process” that involves a proper post-release plan for medical services and housing options that can take months of planning.

“For these reasons, I believe accelerated early release creates significant risk,” he wrote. “As Secretary, I promise to remain diligent and focused on doing all I can to protect those who work and are housed in our correctional institutions.”

Ryan Andrews, a Tallahassee-based attorney who represents Florida inmates, said the facilities are simply not set up to deal with treating the illness, much less stopping the spread. He said so many inmates are rushed to the hospital in their final days because the best treatment in prison happens if there’s a thought the inmate could die. He compared it to the prison system’s handling of Hepatitis C, where the state only began to treat inmates with urgency when some started dying of liver failure in the late stages of the disease.

Based on conversations with inmates, Andrews says sick people are frequently mixing with the healthy and there is a lot of misinformation spreading about how to protect against the highly contagious disease.

“There is only so much prisons can do,” he said. “They are waiting until it gets bad or the person looks like they are dying. ... Their families just find out after they’re dead.”

In some cases, members of the public are stepping in to try to help curb the disease. Debra Bennett, a former inmate and current prisoner advocate, has organized donations of masks, gloves, bleach, face shields, soap, toilet paper and other necessities to Homestead Correctional Institution, where 302 inmates are infected. When she drops off supplies, she notices that guards are sometimes not wearing masks or any other personal protection equipment.

On the day of her latest delivery, two women at Homestead died of COVID-19 — both women Bennett knew well.

“These are my friends. I can’t describe what it felt like to see [Tyra Williams] in an open casket. I couldn’t handle it,” she said. “My frustration is the Department of Corrections takes coronavirus as seriously as [Florida] Gov. [Ron] DeSantis does. It’s not taken seriously.”