E.R. Bradley: At Triple Crown time, a Palm Beach gambler's legacy lingers

This story originally published June 10, 2005

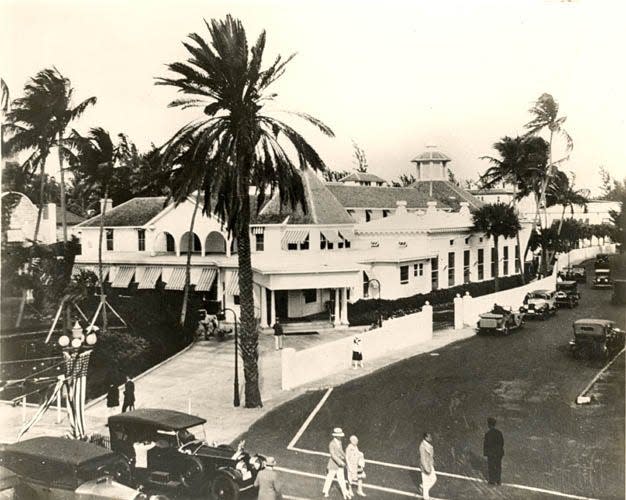

Typical for the Colonel, as he was known, it took place in his Beach Club, an exclusive establishment (read: casino) that he opened on Palm Beach in the late 1800s and operated for 50 years without being robbed or raided.

To most residents today, Bradley's is the name of a popular bar on Flagler Drive, and of a street and a park. Some might recall that without his often-quiet contributions, Good Samaritan and St. Mary's hospitals and St. Edwards Catholic Church might not exist.

But only the graying few might remember that Bradley was one of history's most renowned horse owners and gamblers. Or that at this Triple Crown time of year, the sporting spotlight shined on this area because of a man whose innovations in horse racing still reverberate 59 years after his death.

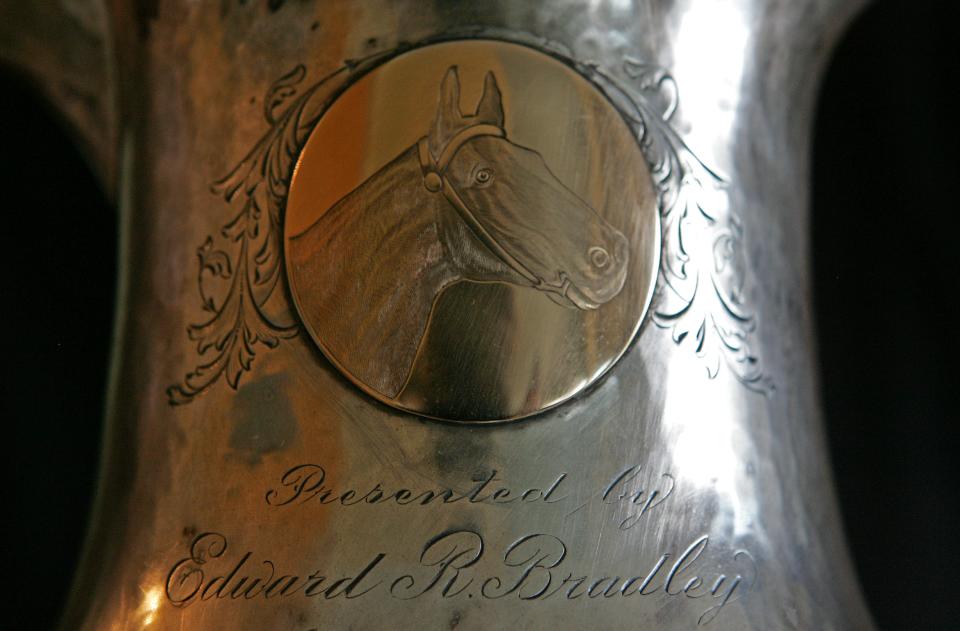

Bradley won the Kentucky Derby four times — more than all but one owner - and swept the top two places twice — more than any owner, period. He won the Belmont Stakes twice. Beyond that, explaining Bradley isn't so simple, because the operator of an illegal casino isn't supposed to warrant official decrees upon his death labeling him "one of the most honored, esteemed citizens" in Palm Beach and the greatest contributor to Kentucky's horse breeding industry.

No, for a casino operator, Bradley surely didn't act like one. Especially that evening when the tearful young woman talked her way into his office and explained that her husband had just lost $5,000 — all their savings — on their honeymoon.

Bradley reached into his desk and pulled out five $1,000 bills.

"I'll give you these on condition you promise me that neither you nor your husband will ever enter this club again," he said, faithful to his edict that the Beach Club be free of whiners and welchers. Tears still flowing, she agreed.

Bradley was a man of steely blue eyes, broad shoulders and heavy starch in his collar, and when he spoke, even the Kennedys and du Ponts listened. So you can imagine the Colonel's surprise the next night when he spotted the husband.

"You were told never to come here again," Bradley said. "You cannot afford that kind of money. Your wife agreed."

"My what?" the man said.

"Your wife."

"Colonel Bradley, I am not married," the man said. "As for not affording it, I think I can. My name is Russell Firestone."

Bradley thought it was magnificent. For years his stock line was, "Any girl who could get the best of a tough old goat like me is welcome to $5,000."

Today, over the phone line, comes more laughter, from a 93-year-old man in Mobile, Ala. Sure, Joe Bailey says, I remember that tale well. Bailey, a nephew of Bradley's, lived with him in the '30s and was by his side for many of his Triple Crown triumphs. Bailey heard plenty of stories of cash coming and cash going.

"He said, 'Not many people are smarter than I am,' " Bailey says. "She put on quite an act."

So did Col. Edward Riley Bradley.

You could bet on it.

Bradley's quest to breed and own the finest racehorses was so boundless, he once fitted a thoroughbred with eyeglasses, an experiment that abruptly ended when said animal bolted directly into the rail.

His gambling exploits landed him on the cover of Time.

Questioned by Louisiana Sen. Huey Long on Capitol Hill, Bradley explained, "I gamble on anything, not excepting spitting on a crack." He bet an elderly groom that he would die within a year of marrying a younger woman. Sadly for the love-struck couple, Bradley was dead-on.

Bradley even claimed to have known Wyatt Earp and Billy the Kid and to have helped capture Geronimo, although proof eluded historians.

"It's such a classic American tale," says John Phillips, who now owns the farm in Lexington, Ky., that Bradley founded. "An Irish guy going into the Wild West. Making a fortune. You're not too sure how. It probably was on the edge of the law, anyway. He's kind of got this wild streak in him. Sort of defies the odds. Comes back. Is a gambler. And he's got a good side and a bad side. . . .

"It's intriguing."

Says Bailey: "He was a man of contradictions. You couldn't believe a fellow that was a professional gambler could get the respect that he got — and I mean from everybody." A testimonial dinner in 1932 included a telegram from President-elect Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Bradley's stature might explain his final Derby victory, in 1933, when stewards ruled that Brokers Tip edged Head Play by a nose in the "battling jockeys" Derby. As they roared down the stretch, Bradley's rider, Don Meade, and Head Play jockey Herb Fisher slashed at one another, even grabbing each other's silks.

As the judges conferred, Fisher whacked Meade over the noggin once more with his whip. Finally, the riders retired to the jockeys' room . . . where they resumed brawling. Meanwhile, with no photo-finish camera, the stewards had to consider a protest by Fisher.

"These stewards didn't hesitate," Bailey says. "They let the race stand as occurred, which is unusual. It was generally known it was because of E.R. Bradley. They didn't want to black his name in racing by calling off the winner."

Although many contend Bradley preferred the company of horses over people, the way he treated employees of both the casino and his 1,292-acre Idle Hour Farm was extraordinary. Wives whose husbands went off to war or died still found paychecks in their mailboxes. After one of his trainers died, Bradley adopted the man's daughter.

Bradley knew what the other side felt like. When he was denied entry into Lexington's exclusive country club because he was an Irish Catholic, he and designer Donald Ross built Idle Hour Country Club, which remains one of the most exclusive venues in Kentucky.

Bradley also took care of his black employees, and this was during an era in which no one winced when a Bradley horse named Black Servant placed second in the Derby. Bradley named several horses after black employees.

Before he died at 86, Bradley wrote a lengthy will that included $500 for each employee of the farm, "both colored and white." Eight black employees served as his pallbearers.

"He was really ahead of his time in both race and compassion for people to whom those things were not as openly and vigorously expressed," Phillips says.

Says Bailey: "He saw no color. He saw individuals. They were part of a family. . . . They weren't treated as servants."

But horses . . . horses occupied the warmest part of Bradley's heart. He called them "my children," holding elaborate funerals when they died and clutching a handkerchief when recalling his favorites, especially Bit of White.

"I can't help being sentimental about her," Bradley once said. "I've known her from the moment she was born. I've slept with her, eaten with her, nursed her through illness, and a thousand times have felt her nose against my cheek. I know I love her best of all."

In an article for American Legion magazine, Bradley said it had nothing to do with financial rewards.

"The thrill of victory always was and always will be greater than the thrill of gain," he wrote. "Does the father watching his son straining every muscle in a hundred yard dash need the added incentive of a bet on his boy to be thrilled to his fingertips? Real thrills come from the heart rather than through the payoff window."

Behave Yourself gave Bradley his first Kentucky Derby victory, in 1921. Five years later came another highlight. With Dick Thompson recovering from appendicitis, Bradley assumed training duties - he always figured he knew more about horses than anyone in his employ - and guided Bubbling Over and Bagenbaggage to a 1-2 finish.

As if an exclamation were needed, Bradley added one by winning $87,000 on a bet he made with another owner over whose horse would fare better.

Burgoo King (1932) and Brokers Tip put Bradley No. 2 on the Derby winners' list behind Calumet Farm, but this week on the horse-racing calendar - Belmont Stakes week - was especially significant to him.

"He thought the big race was the Belmont," Bailey says. "He said the horse there was at full growth, matured. It would run truer to form, he would say, whereas an outsider could win the Derby."

Bradley won the Belmont in '29 with Blue Larkspur and in '40 with Bimelech, whose runner-up finish in the Derby prevented a Triple Crown.

"In a quiet way, he is still profoundly influential," Phillips says. "He assembled in the '20s and early '30s the best broodmare band that this country had seen. Although dispersed shortly after his death, it's still responsible for some of the great racehorses of today."

Born in 1859 into a Pennsylvania family of modest means, Bradley apparently acquired his wealth in a wager after a gamble by his brother nearly wiped them out. After that, few in need were turned down for a loan, and Bradley never did a double-take when repayments were made 20 or 30 years after the fact.

But he ran the Beach Club with precision and was never robbed, outside of the $5,000 runaway bride. He installed revolving tables that could be instantly concealed. Only members were allowed - non-Florida residents only - and formal attire was required after 7 p.m. The restaurant was said to be the finest in the state, perhaps the country, and it had to be considering the exorbitant $1 for the signature Green Turtle Soup.

"If not for Bradley's casino, Palm Beach would have been a flop," says Tom Cunningham, who wrote a thesis in 1992 at Florida Atlantic University entitled The Life and Career of Edward R. Bradley.

Cunningham figures Henry Flagler's public stance against a casino in Palm Beach was more charade than chagrin. Most residents were indifferent. Once, a native was showing around an out-of-towner who asked whether the white structure marked "BC" wasn't the Beach Club.

"What building?" the host replied. "I don't see any building."

As per Bradley's will, the Beach Club was demolished upon his death and nearly all the gambling equipment was thrown out. Today, also as Bradley wished, it's the site of a small park that greets motorists driving to Palm Beach over the Royal Poinciana (north) bridge. The majority of the fountain at the Beach Club's entrance is virtually all that remains.

But so has the legacy, now.

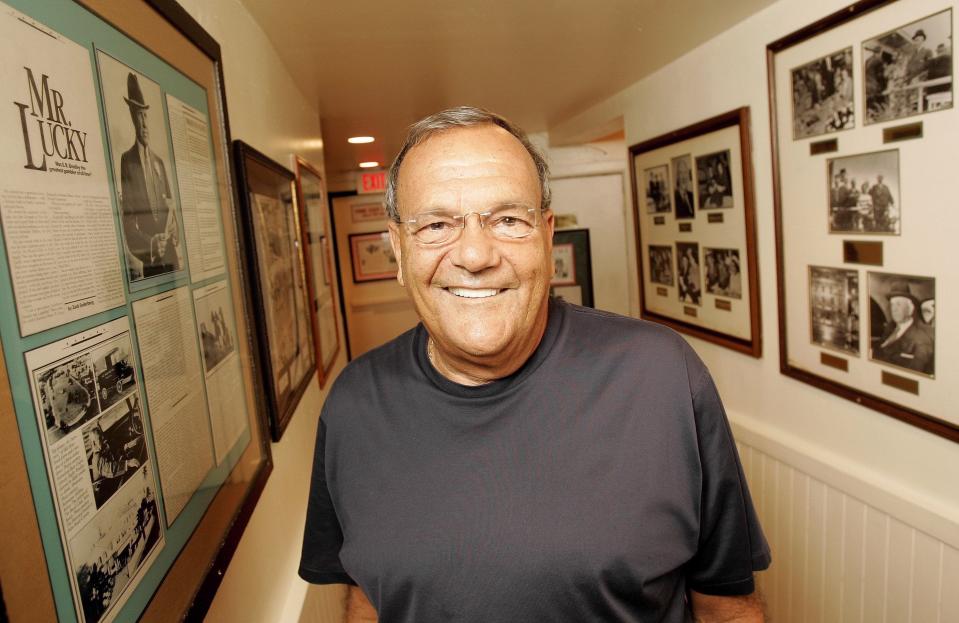

Frank Coniglio, a horse enthusiast and restaurateur, read a book detailing Bradley the horseman and "immediately felt connected to him." When Coniglio and his partner opened a restaurant in Maryland, they named it E.R. Bradley's Saloon, then had no option but to copy the name when they opened a restaurant/bar adjacent to where the Beach Club once stood.

So, contrary to assumption, the bar — which was moved to West Palm Beach in 1999 — has no direct lineage to the man. Which makes it all the more special to Bradley's descendants.

"I feel great about it," says Port St. Lucie's Ed Bailey, 80, Bradley's great-nephew. "He's running it like a museum, perpetuating his memory."

Adds Joe Bailey: "For somebody with absolutely nothing to do with him relative to bloodline or any way else, to read his life story and then do what he did . . ."

Three years ago, James L. Jensen, a local historian who hopes to write a book on Bradley, visited Bradley's grave in Kentucky and told Coniglio it was in a state of disrepair. Coniglio paid to have the site restored and has a dozen roses placed there every Dec. 12 to mark Bradley's birthday.

Even though lease problems meant moving the bar to Flagler Drive, the memories came along. Parties are held every Dec. 12 and for major horse races (including Saturday's Belmont). The walls are covered with photos and stories of Bradley's success.

Once, a former jockey of Bradley's visited, regaling Coniglio with a story about how Bradley told him never to whip his horse. The rider did, once. Bradley immediately turned him into his chauffeur.

"Sometimes I'm sitting in that office and I'll hear people out there talking about the pictures," Coniglio says. "And I'll step out of the office and try to explain something to them. Every once in a while some horsemen happen to stumble by and they've never heard of E.R. Bradley until they start reading what's on the walls. I'll go to a cocktail party and people will say, 'How'd you come up with that name?' People have heard the name but might not have any idea who he is and what he did until you start telling them.

"And then they're amazed."

- hal_habib@pbpost.com

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: E.R. Bradley: The legacy of a famous Palm Beach horseman and gambler