Early elementary reading skills can impact future success. Here's how to help your child.

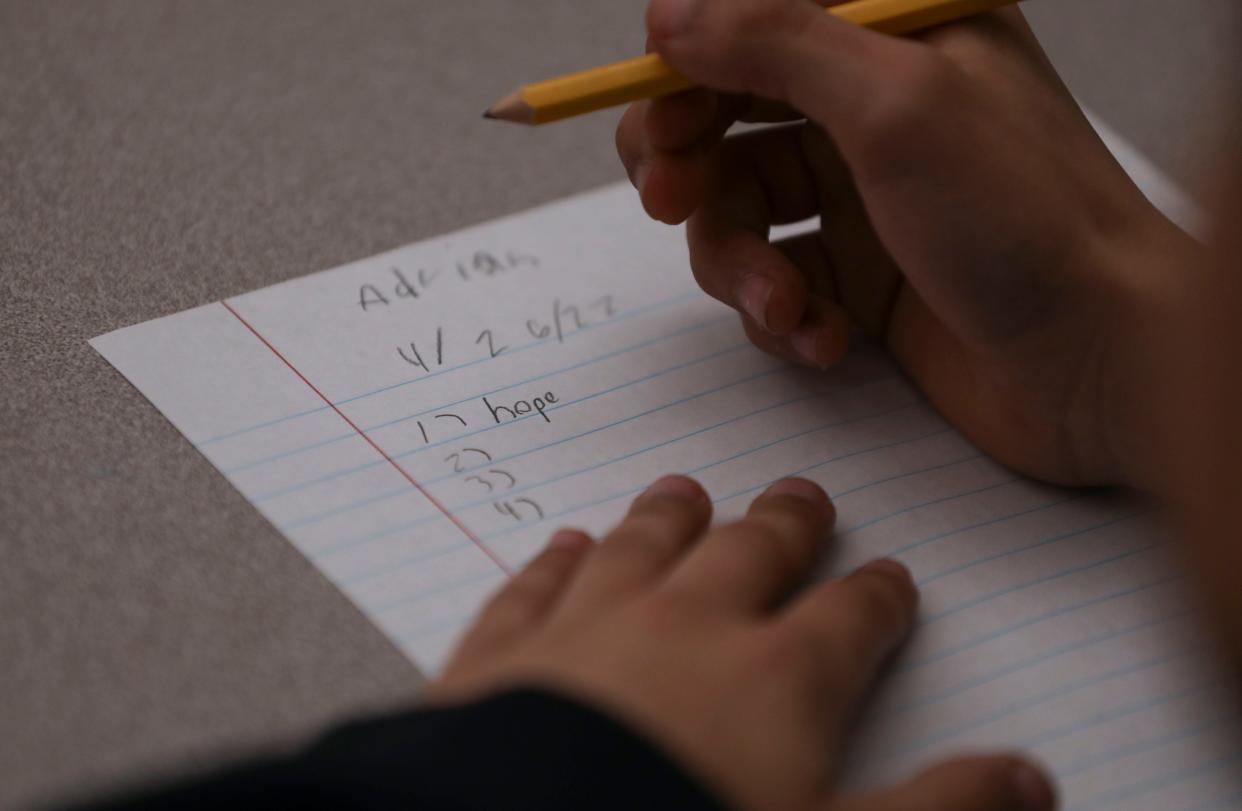

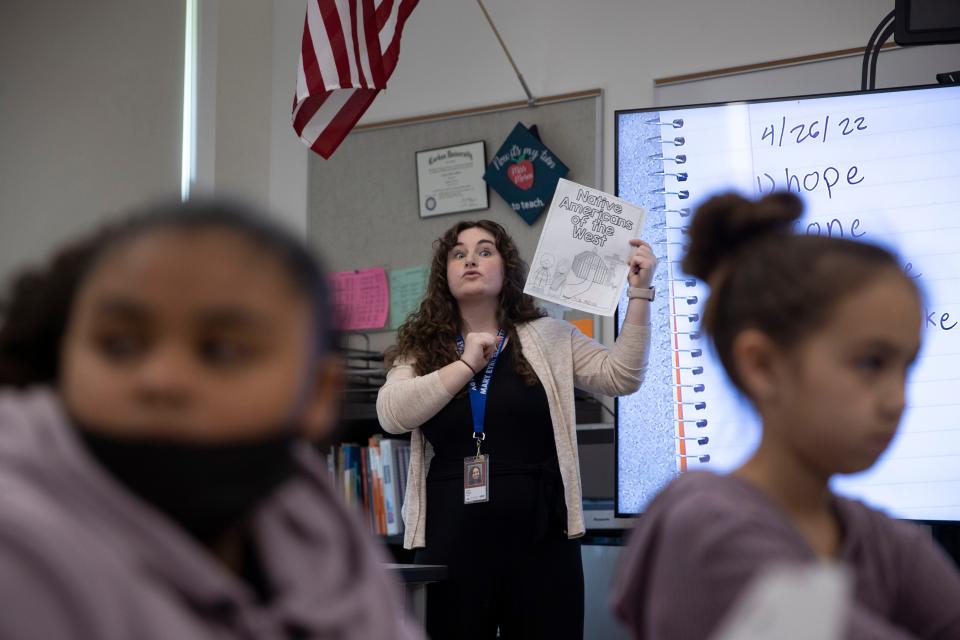

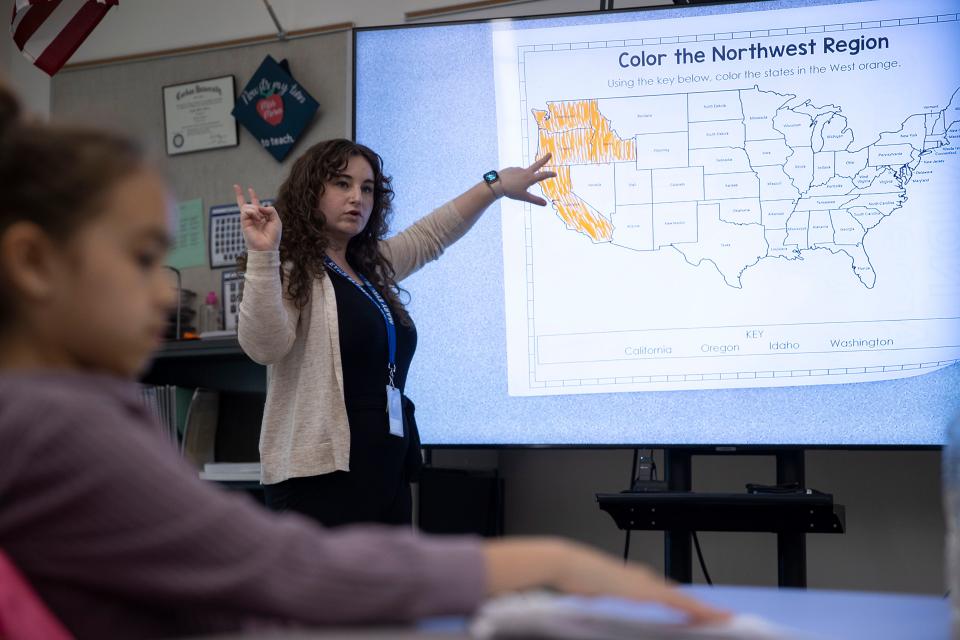

SALEM, Ore. — Fourth-grade teacher Angela Mosca moved around her classroom at Mary Eyre Elementary School in Salem, Oregon, one April morning as her students followed along with the day's assigned reading. She read a paragraph aloud, pausing on key vocabulary words. The students said the words in unison to prove they were paying attention.

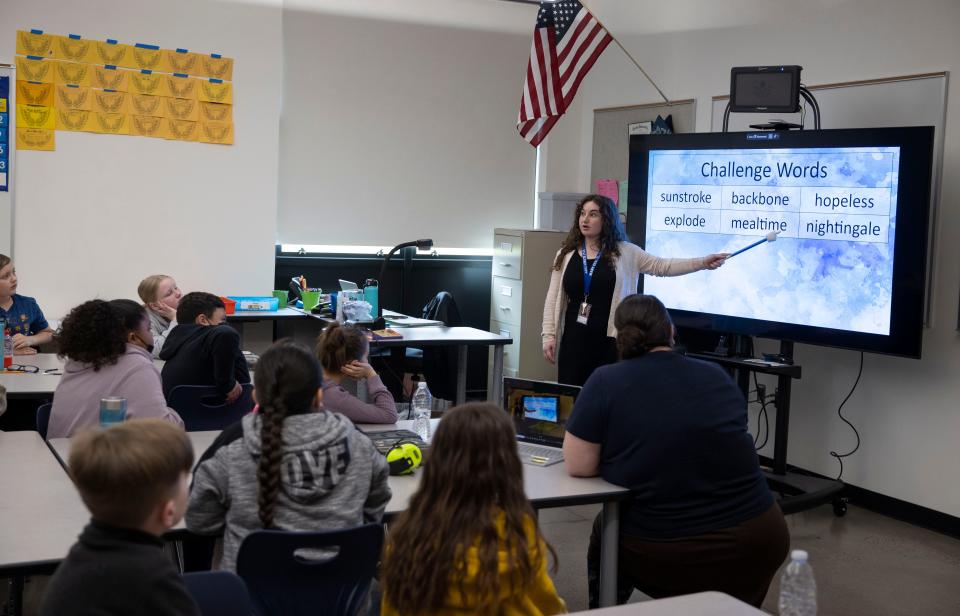

Mosca structured time in a reading hour later that month to review foundational phonics, showing students how to break down and sound out a word, especially ones with multiple syllables.

"If a student leaves kindergarten or first grade without knowing their letter sounds, for any number of reasons, they may not be able to comprehend a grade-level text by the time they get to me in fourth grade," Mosca explained.

"We all learn at different speeds," she said, "and sometimes a student needs to slow down and work on those foundational skills."

A child's ability to read “on grade level” by third grade is often a key indicator of future academic success.

Research from the University of Chicago found that for 85-90% of poor readers in the K-12 setting, prevention and intervention programs implemented before the third grade can increase reading skills to the average level. However, if intervention is delayed until age 9, about 75% of children will continue to have difficulties learning to read throughout high school and into adulthood.

A long-term study by the Annie E. Casey Foundation found students who were not proficient in reading by the end of third grade were four times more likely to drop out of high school than proficient readers.

Prison literacy: The path to prison is often paved by illiteracy. Yet many prisoners aren't being taught to read.

Low literacy is not a direct determinant of a person’s chance of being incarcerated. But corrections experts have long recognized a connection between poor literacy, dropout rates and crime.

Students who drop out of high school are three and a half times more likely to be arrested than graduates, as cited by Stanford University. And while those with the lowest reading scores nationally account for just a third of students overall, this group accounts for more than 63% of all children who do not graduate from high school.

The National Adult Literacy Survey found about 70% of all incarcerated adults cannot read at a fourth-grade level, with some estimates showing 85% of all minors who interact with the juvenile court system are functionally illiterate. Nationally, 68% of all males in prison do not have a high school diploma.

How literacy is defined, how prisoners are tested and how their needs are addressed varies from state to state, with little to no federal oversight.

Some students are worse off than others

In Oregon, 36% of fourth-grade students tested by the National Assessment of Educational Progress were below basic reading levels in the 2019-20 school year — a slightly larger percentage than the national average of 35%.

But that number jumps to 46% for the state's economically disadvantaged students, 52% for Hispanic or Latino students and 71% for students with disabilities.

Oregon's K-12 dropout rate in the 2020-21 school year was down to 1.8%, according to the latest available data.

But again, that rate climbs to 2% for Hispanic or Latino students, 2.22% for students with disabilities, 2.88% for American Indian or Alaska Native students and 3.19% for Black and African-American students.

Similar disparities are seen when it comes to school discipline.

In 2011-12, Black youth represented 16% of the juvenile population but 34% of the students expelled from U.S. schools, according to the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights.

School leaders, state agencies and lawmakers say they are focused on improving third-grade reading fluency, making it a target of Oregon's Student Success Act.

The Student Success Act, passed in 2019, allocates about $2 billion per biennium to improving early childhood education and K-12 schools statewide. The aim is, in part, to "advance equity by reducing and eliminating disparities."

Individual school districts largely decide how to spend their portions of the money, as long as they fall under specified categories. To address reading gaps, for example, schools could buy new reading curricula and pay for added staff training.

Educators such as Mosca are working to fill any reading gaps seen in schools, including those that may have widened during the pandemic.

A look into the classroom

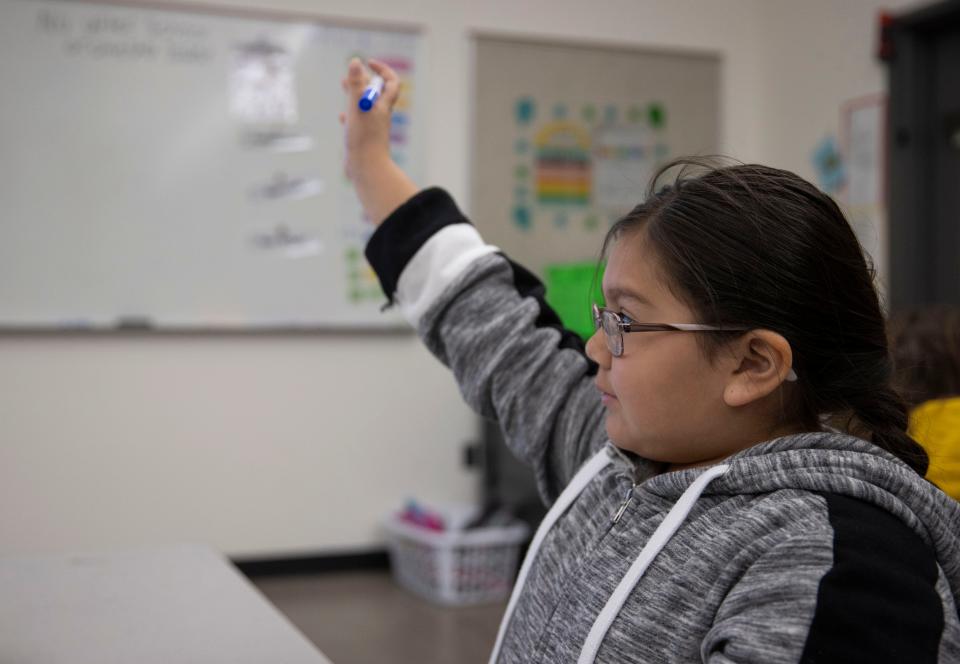

Mikailyn Parish, 10, enjoyed reading about Native Americans in her fourth-grade class this April, continuously saying "wow" as she flipped through pages covered with illustrations and maps. She held the book with both hands, often the first to say the words aloud when prompted by Mosca, even if she said them quietly.

When her teacher posed questions to the class, Mikailyn's arm shot up.

Mosca said some widely believed misconceptions about reading are that everyone learns how to read in kindergarten, that reading is easy for everyone or that we all learn the same way.

"When students keep moving up to the next grade level without their specific reading needs being met, they fall further and further behind their peers," she said.

Mosca said she's seen students who know they are behind in reading act out or lack confidence.

"Oftentimes, when a student struggles in reading, they try to earn peer and/or adult approval in other ways, in an effort to avoid being made fun of or laughed at," she said. "They may lash out during reading lessons, or try to distract the class so they can avoid doing a task they are not confident in. They may also avoid reading in casual social situations where their peers are involved, like reading the lunch menu."

Reading is one of student Parish's favorite activities. She said her favorite part is learning new words and how to pronounce them.

"Sometimes when you're stuck on a word, it's OK," she said. "You just have to sound it out."

Addressing special needs

Portland, Oregon-based attorney Kathie "K.O." Berger, who worked as a juvenile defense attorney for more than 30 years, has noticed trends when it comes to her clients with speech and language disorders.

In some cases, she said, the individual's school recognized but did not provide the needed services. In others, no one throughout the student's educational career ever noticed an issue or formally evaluated and diagnosed them.

"I've become a big proponent of encouraging lawyers to look at that possible disorder because it so affects how somebody is able to communicate in the world," Berger said. "My guess is there are a number of people incarcerated, both in Oregon and throughout the country, that have undiagnosed language disorders."

By the first grade, roughly 5% of children have noticeable speech disorders, including stuttering and dysarthria, according to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders.

Dyslexia — a neurological disorder characterized by difficulty reading — is estimated to affect 5-15% of Americans. And while the exact prevalence of dysgraphia — a neurological condition affecting writing — in the U.S. is unknown, an estimated 10-30% of children experience difficulty with writing, some of which can be attributed to dysgraphia, according to a 2020 study in the journal Translational Pediatrics.

No national studies as of 2019 have been conducted regarding the prevalence of dyslexia among prisoners, according to Prison Legal News. However, a study of Texas prisoners in 2000 found that 48% were dyslexic and two-thirds struggled with reading comprehension.

Often, Berger argued, schools look at these individuals and think, “Oh, you have the capacity to do better, so you're just being lazy, or you just don't care.

"(It is) much more pervasive in the criminal justice system than I think anybody really realizes," she said.

What can families do to improve literacy early on?

More than socio-economic status or race, Mosca said what she's noticed really impacting students struggling with reading — or school in general — is the value families put on education.

Home life, the school experience and several other factors play into a student's ability to learn and thrive. Numerous studies, including one conducted over the course of 20 years, show that things as simple as the number of books in a home impact the number of years a child will likely stay in school.

"Some families hold to the idea that adults go to work, and kids go to school – school is a kid’s 'job,' so to speak," Mosca said. "To other families, school or education is not as important.

"Teachers can only teach to the extent that students are coming to school, and parents are supporting the learning at home."

Experts suggest parents and caregivers start by talking with their children throughout the day using short, simple sentences. Talking with them even before they can speak will help them later when they learn to read and write, according to the U.S. Department of Education. Families should also read aloud to children for at least 30 minutes a day and help them to learn to read on their own.

Reading Rockets has reading tips for students with learning disabilities and other special needs, like helping them create mental images or drawing connections between what they're reading and facts about themselves.

Tips to improve literacy with your reader

Increase vocabulary by engaging in activities and providing explanations that illustrate the meaning of individual words:

Work on crossword puzzles together and play word games like Scrabble and Boggle.

Point out interesting or unfamiliar words you or your adolescent encounter while reading or playing word games and talk about their meaning.

Discuss the meaning of important terms from the news, parents’ careers, family finances, etc.

Build fluency by engaging in activities to help your adolescent read text at an appropriate pace and with expression when reading orally:

Establish a regular reading schedule in the evenings and/or on weekends and during breaks.

Encourage your child to read a wide variety of texts including fiction and non-fiction.

Help adolescents find magazines or books that relate to their interests in libraries, bookstores and online.

Listen carefully to your adolescents read orally to ensure they are reading at an appropriate pace and with expression.

Help your adolescents pronounce challenging words correctly.

Improve reading comprehension by engaging in activities to help adolescents understand what they are reading:

Ask questions like, “What do you think this story will be about?” before reading, such as, “What do you think will happen next?” during reading and “Why do you think the author ended the story the way he did?” after reading.

Encourage adolescents to write down questions they may have as they read the text such as, “I wonder why the two characters saw the same situation so differently?”

Talk about high-interest topics with your reader, help them find texts that address these topics and show them the types of writing they will need to do in the future.

Read the same book as your adolescent and discuss what happened after each chapter.

Connect reading and writing at home to topics that are being addressed at school.

Take time to discuss texts that adolescents find interesting or important.

Partner with your child's school by keeping in touch with their teachers to ensure they are working on grade level:

If you think your adolescent needs extra help, speak with school counselors, administrators and/or teachers to determine the best intervention materials and instruction to meet their needs.

Ask content area teachers and interventionists how you can support literacy development at home.

Tips source: The Institute of Education Sciences

This project was completed thanks to funding via a fellowship with the Education Writers Association.

Follow Natalie Pate on Twitter @NataliePateGwin.

This article originally appeared on Salem Statesman Journal: How elementary school reading skills impacts future success