Early history of Robertsville: 1875 – Epilogue (what happened to the gold?)

In this fourth and final article in the series, Dennis Eggert finishes the schools and closes out with some additional information on the legend of the lost gold buried by Collins Roberts. He has asked me to correct a couple of mistakes in the first column: The first church here was called the East Fork Baptist Church, not the Holston Baptist Church. The East Fork Church did belong to the Baptist Holston Conference. Secondly Richard Oliver was the son of Douglas, not his father.

Robertsville Academy

Just after 1875, the Oak Grove Academy located in Robertsville was chartered. Shortly afterward, it became known as the Robertsville Academy. The exact location of where the Robertsville Academy existed is unknown but there is tantalizing evidence of where it may have been. In 1883, the Robertsville Academy Board of Directors signed a contractual agreement with Dr. Henry Seinknecht for the use of a well on his property. Seinknecht’s land consisted of over 100 acres that today is the site of the Oak Ridge High School. He bought this land from his father-in-law, J. D. Tadlock, who previously bought the southwest section of the vast Douglas Oliver estate. This parcel of land also included the spring that today feeds the Oak Ridge Swimming Pool.

The agreement between the academy directors and Dr. Seinknecht identifies that in addition to the well located nearby the school, there was also a stone house on the property. This would strongly indicate that the well was at the spring that today feeds the Oak Ridge Swimming Pool. Perhaps the stone house was a storage facility that, in the past, stored grain for Oliver’s massive distillery operation. If this is accurate, then the Robertsville Academy would have been located somewhere nearby present-day Grove Center. It is ironic that many people today are not aware that this school existed.

Epilogue

After 1879, there would be more progress to come. The Robertsville High School would be built transferring education from private ownership to government ownership. Additionally, the Woods Chapel and School located near present day Cedar Grove Park would continue to educate African American children. Thanks to the efforts of Elijah Woods, an African American Union Civil War veteran who served in the U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery Regiment, African American children in Robertsville could obtain an education.

Although the cultural landscape of this era has virtually disappeared, a visit to the Oak Ridge historic cemeteries can take us back in time and reveal the names of those individuals who lived here and made Robertsville a vibrant community. Of all the original Robertsville land barons, Collins Roberts has the only identified grave. Within the historic Robertsville Baptist Church Cemetery located behind Willow Brook Elementary School, an impressive obelisk hidden within the low-hanging branches of a massive cedar tree marks the location where Collins Roberts mutely lies in repose.

The Legend of the Buried Robertsville Gold

An early history of Robertsville certainly would not be complete without addressing the legendary Collins Roberts buried gold hoard. This story has persisted through time and even been written about. In George Robinson’s book, "The Oak Ridge Story," he reveals that just before the Civil War, Collins Roberts decided to quietly sell his slaves, accepting only gold coins for payment. Being leery of thievery and banks, Collins buried his gold. Shortly afterward in 1860, he died taking the location of his buried treasure with him to the grave.

This begs the question, how much wealth did Collins Roberts have in 1860 just before he died and what happened to it? According to the 1860 U.S. Census, his real estate value was $25,000 and his personal estate value was $300,000. Today, $300,000 is worth $10.4 million.

From the 1860 U.S. Federal Slave Census, we know that Collins Roberts owned 40 slaves. No documentation exists revealing their fate. Additionally, no will for Collins Roberts has been found nor does it appear that his children received an inheritance.

Son James died in 1862. In 1867, a nuncupative will witnessed by his sister Abiah indicated that James left his wife some land in Dutch Valley. He wished that she would dispose of this land and buy more suitable land which would be more advantageous for the family. Neither does it appear that daughter Abiah received any significant wealth after Collins Roberts’ death. The 1870 census revealed that his daughter, Abiah, and husband Clark Crozier’s wealth had significantly declined from 1860. Certainly, it appears that Collins Roberts’ wealth is unaccounted!

The whereabouts of Collins Roberts wealth became local legend. People came from all over the South searching for this elusive treasure. The stories of Collins Roberts’ buried gold persisted even up to the time the government condemned the land in 1942. Local historian John Rice Irwin told me of a memory he had. As a young boy living here, he also heard stories of this buried gold. John remembered a meeting held by the government in which the local citizens were told of the impending purchase and their need to immediately vacate. In desperation to keep his land, one concerned citizen asked the government official, what about the buried gold? Everyone knew that his question was futile, and his concern was ignored.

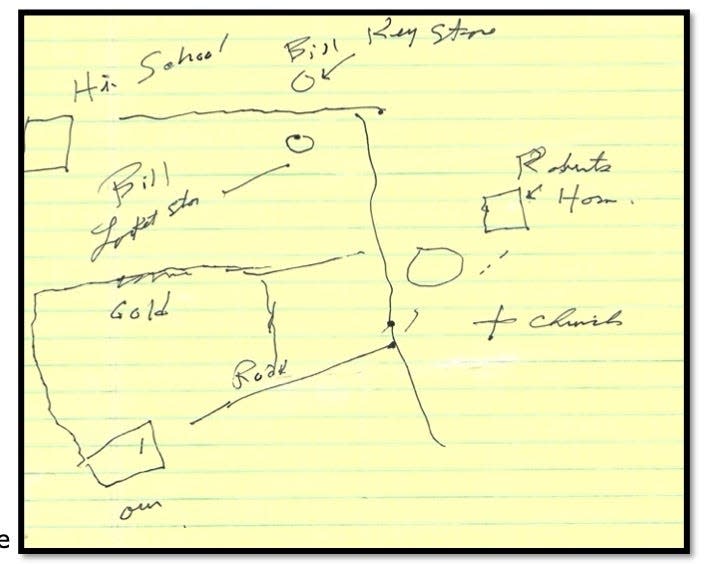

Some time ago, I visited John Rice Irwin who, at the time, was living in an assisted living facility. Although his body was frail, his mind was still as sharp as a tack. Our conversation ultimately turned to what John knew about the Collins Roberts' buried gold. John told me that as a kid living in this community, he too had personally searched for it. At that point I questioned John where it could be. He stated that he was told by his neighbors of two likely places. The first place was on a dip atop East Fork Ridge. Standing at Robertsville High School, now Robertsville Middle School, it would be due south as the compass points to the East Fork Ridge location.

The second location John told me was near the site of the old Collins Roberts’ homestead, which today is at the western intersection of Robertsville and Raleigh roads. At that point, John drew a map for me giving greater detail. As he drew the map, his eyes lit up as though he was still living here in this bygone era.

“Somewhere," he said as he pointed to an area of the map, “is where the gold was buried.”

He added, “Standing in front of the Collins Roberts home you could throw a stone up a rise and within this stone’s throw was where the gold was buried.”

“John,” I said, “that would be somewhere behind present-day Inca Circle!” He just smiled and said, “That’s what I was told.”

My thanks to Fred Eiler for his assistance in the research of this article. Also, I wish to thank Charles Manning for sharing his research on early Anderson County land grants. Additionally, I am grateful to Ron Raymond for creating the maps used for this article.

***

Thanks to Dennis Eggert for the research and documentation of the early Robertsville history. It is good to know the history behind our area. His in-depth look at the details makes the history come to life. Thanks again Dennis! (Now, don’t you all go digging for gold!)

This article originally appeared on Oakridger: Early history of Robertsville: 1875 – Epilogue (where's the gold?)