East Charlotte woman refuses to give up fight to save 100-year-old oak from chainsaw

Just after a gentle bend on Margaret Wallace Road, not far from the backed-up traffic of Independence Boulevard, looms a massive tree whose size is surpassed only by its age.

The willow oak, the same species that gives Myers Park its famous canopy, is 75 feet tall. Its crown, which turns yellow-orange in the fall, is as wide as a tractor-trailer.

It has stood there for roughly 100 years, far longer than the subdivisions that are now commonplace along the road, said Barry Gemberling, an arborist with Arborguard Tree Specialists.

But its days may be limited.

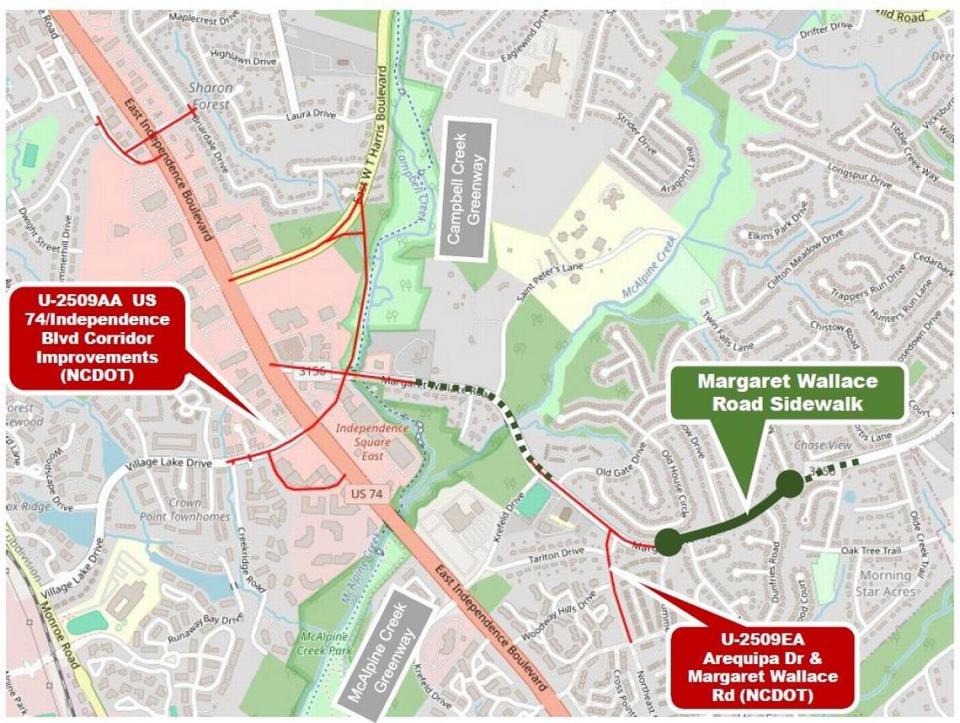

The behemoth’s roots stand in the way of a $3.6 million sidewalk project set to begin in late 2025, Charlotte officials say. The sidewalk will stretch along Margaret Wallace Road between Summerfield Ridge Lane to Marshbrooke Road.

If the tree is not taken down, compacting the ground for the sidewalk and adding drainage could damage its roots, city spokeswoman Tabitha Warren wrote in an email to The Charlotte Observer. That could cause the titan to become a public hazard by increasing the risk that parts of it fall down.

Amanda Davis, owner of the front yard where the giant tree stands behind a wooden ranch fence, isn’t convinced. And she’s fighting to preserve it.

“It’s really gotten under my skin,” said Davis, 29. “I know it’s wrong.”

‘Save this tree’

City officials told Davis about the planned sidewalk last spring, though it was unclear then how it would affect her property, she said. In October, contractors representing the city knocked on Davis’ door and offered $2,100 for the portion of her land hosting the tree. She said no.

That month, to try to prevent the city from taking any of her land against her will, she met with members of the city’s Planning, Design & Development department and the real estate contractors, Davis said. She asked that they find a way to continue the project but save the willow oak. They met again in November and again this month, when Davis brought Gemberling, the arborist, and her attorney.

“That’s when it basically became clear that they’re just not willing to preserve the tree,” she said.

The city had upped its offer for the land and removing the tree to roughly $15,000. Again, Davis said no.

Officials are now looking for alternatives that would preserve the willow oak, Warren said.

In the meantime, Davis has taken her quest public. Last week, she wrapped the oak in a large banner that reads “Save Me” and posted a 24-foot red and white banner on her fence. “SAVE THIS TREE,” it screams in capital letters.

The banner hosts a QR code too that links to her petition on the website change.org.

“This tree has stood sentinel at this spot for over 100 years,” Davis wrote on her petition’s website. “It has seen the growth of our city and sheltered generations of wildlife. Today, it exists in fine health and there is no justification for its removal. We see evidence all around our city of large trees living harmoniously among roads and sidewalks. It can be done.”

A healthy heritage tree

As of Sunday, more than 950 people had signed the petition, part of a campaign that impresses Gemberling.

“There aren’t that many people who have this diligence or this aggressiveness in trying to save a tree,” he said. “Quite often, I think people have made it easier for the cities in situations like this.”

Gemberling, who also had praise for the City of Charlotte’s tree-saving practices, inspected the old oak last month for Davis. He documented a number of dead limbs and four large stems growing up from the trunk, which increases the risk of breakage during future storms.

But the tree is in fair condition, he said, and has more life ahead.

“It is not dying or digressed beyond the point of recovery and remedial treatments,” Gemberling’s report said.

Removing the tree would contradict Charlotte’s efforts to preserve such specimens, Davis said.

In Charlotte, the willow oak qualifies as heritage tree, she explained. Heritage trees have at least a 30-inch trunk diameter at 4.5 feet off of the ground. Davis’ tree, by comparison, has a 58-inch diameter.

Last year, city officials signaled the importance of heritage trees by adding a provision to Charlotte’s Unified Development Ordinance that protects them. People who remove a healthy heritage tree could be fined $50 per diameter inch, which would total $2,900 in this case. They’d also have to plant a tree and pay a $500 mitigation fee.

Charlotte, the City of Trees?

Charlotte’s desire to protect its trees and make room for growth have long been at odds.

For more than a decade, city leaders have talked about protecting — even expanding — Charlotte’s prized canopy.

But study after study has shown that Charlotte is losing trees. One found that Charlotte lost three acres of trees on average every day from 2012 to 2018 — or about 7,000 total acres. That study, conducted by the University of Vermont, said trees covered 45% of the city.

Last November, the consulting firm PlanIT Geo released a report showing that tree loss had slowed. It said Charlotte lost less than 1,000 acres from 2018 to 2022, and that trees covered 47.3% of the city.

Some questioned PlanIT Geo’s study. Five GIS experts told The Observer in December that the findings may not be as accurate as previous ones.

Their concerns stemmed from the way PlanIT Geo measured the city’s canopy. The company used National Agriculture Imagery Program data — aerial images — and machine learning to calculate canopy change.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s data is good for detecting trees, the experts said, but imagery alone has a hard time differentiating a tree from a bush or detecting a tree in the shadow of a building.

Worth the fight?

One of Charlotte’s most dedicated advocates for protecting the city’s tree canopy said he’s impressed by Davis’ desire to save the willow oak, but he sees another option.

The tree is old, likely nearing the end of its life and structurally flawed because its trunk is divided into different vertical stems that could snap in a storm, said Doug Shoemaker, a UNC Charlotte ecologist who has studied Charlotte’s canopy for years. Because it stands alone, unprotected from high winds, it is more vulnerable to damage.

The city could replace the old tree with three, four or five young ones, Shoemaker said. A stand of trees would grow to provide more ecological benefits than a single giant, he said.

“There are some really positive things that could come from this,” Shoemaker said. “You could actually end up with a better outcome over time if you did it correctly.”

Gemberling favors letting the tree stand. Despite its tree’s age, it could live another 50 or 100 years, he maintains. Most of its root extend away from the road and into Davis’ yard, where there is plenty of undisturbed soil, he said.

And treatments, such as adding nutrients to the soil, managing diseases and insects and installing flexible cables to support the tree where the trunk split would reduce its risk of breaking.

Davis wants to preserve what she has rather than gamble on what might come next.

“If they take out this mature tree and replace it with however many mitigation trees, there’s still no protections in place for them,” Davis said. “And who knows if they’ll ever reach maturity. There’s no guarantee.”

NC Reality Check reflects the Charlotte Observer’s commitment to holding those in power to account, shining a light on public issues that affect our local readers and illuminating the stories that set the Charlotte area and North Carolina apart. Have a suggestion for a future story? Email realitycheck@charlotteobserver.com