'It will eat you alive': How Vietnam POW from Manalapan let go of his hate

For many years, David Drummond has told his incredible story to students: How, as an Air Force pilot, he was shot down during the Vietnam War, survived a harrowing ejection as his B-52 bomber plummeted end over end to the ground, then was captured and held as a prisoner of war for 98 grueling days.

On Friday, when the longtime Manalapan resident speaks as part of a National POW/MIA Recognition Day vigil at Memorial Park in Metuchen, he will have a touching epilogue to share.

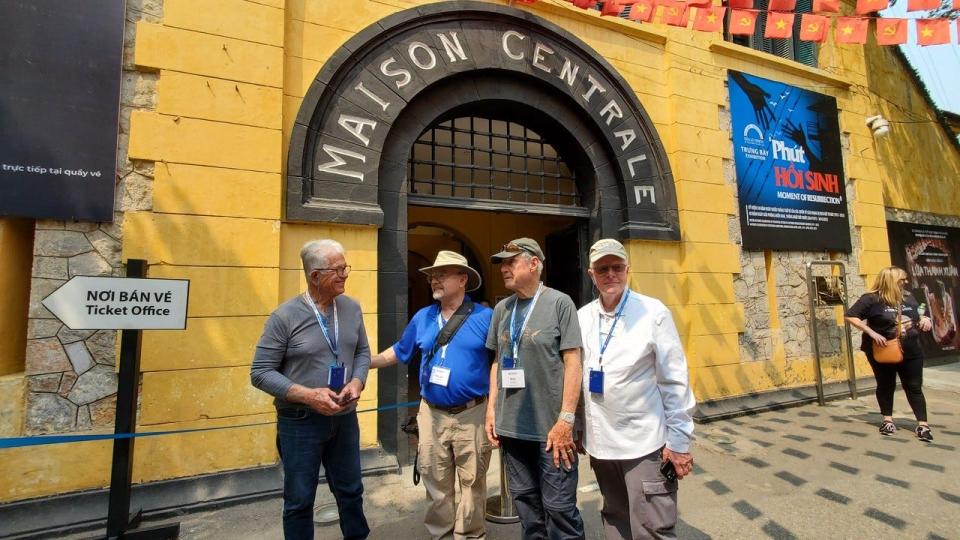

For three weeks this past winter, 50 years after his release from the infamous prison nicknamed the “Hanoi Hilton,” Drummond returned to Vietnam for the first time. He toured what’s left of the Hanoi Hilton, which has been turned into a museum. He and wife Jill Drummond visited a former Viet Cong medic and his wife. Along with a handful of other POW survivors, he attended a dinner with former enemy pilots, some of whom had shot down Americans.

The experience was a powerful exercise in reconciliation, and it informs his message to students and anyone else who will listen.

POW tale: Why it took 80 years for Middletown WWII vet beaten by Gestapo to get his Purple Heart

“You cannot hate. Hate destroys you,” Drummond said. “You have to let it go, or it will eat you alive.”

Nearly 800 Americans were known to be held as prisoners of war in Vietnam, according to the U.S. government. As the number of survivors dwindles over time — there are far fewer ex-POWs from later wars — Drummond knows their story has to be told.

This week's vigil, which is organized by Vietnam Veterans of America Chapter 233 of New Jersey and is open to the public, begins Friday at noon and closes with a ceremony that starts Saturday at 10 a.m.

Anne Rivera, principal of Saint Joseph High School in Metuchen, is bringing 20 students Friday to hear Drummond speak.

“It’s not every day you get to see history in person,” she said.

'You can't just be a taker'

Now 76, Drummond graduated from Westwood High School in Bergen County and Newark College of Engineering (now the New Jersey Institute of Technology). Through Air Force ROTC, he was was commissioned as a second lieutenant. On Dec. 21, 1972, his plane was shot down during a bombing raid over North Vietnam. He and his crewmates bailed out quickly — remarkably, all survived — but were taken prisoner by the North Vietnamese in short order.

For the next three months, he fought off deprivation (his diet consisted of cabbage soup and fried pig fat), isolation and brutal living conditions until the Paris Peace Accords led to his release in March 1973.

“Some people say, ‘I don’t know if I could have withstood that; I don’t know if I could have survived,” Drummond said. “People give themselves less credit than they should.”

Box of WWII letters holds amazing story: Lacey woman learned POW fates through Nazi radio

Awarded numerous medals for valor, including the Bronze Star, Drummond moved to Manalapan in 1977 and spent three decades as a pilot with American Airlines.

Post-traumatic stress disorder was not well understood in the aftermath of Vietnam, but toward the end of his career his began to notice symptoms and sought treatment. Jill Drummond, who is a clinical psychologist, chronicled their family’s experience in a book titled, “Allies in Healing: A Couples’ Toolkit of Resources for Recovering from Combat PTSD.”

Despite his hardships, Drummond does not discourage people from entering the military, and in fact promotes shared sacrifice as a civic virtue — whether through community service or the armed forces.

“You have to contribute back to society,” he said. “You can’t just be a taker; you have to be a giver. It’s good for your mental health, too.”

He’s also worked to help change society’s Vietnam-era mindset about war.

“They blamed soldiers for actions of politicians and government,” he said. “It’s not the military that decides when to fight. It’s your government — your elected officials. One of the goals of the Vietnam Veterans of America was to make sure that (misconception) was never forced on the next generation of soldiers. That whole attitude has been changed.”

'What Bronze Star?': Wall Vietnam veteran battles red tape, gets medal 55 years later

Locally, Drummond has been involved in recovering and burying the cremated remains of veterans and their spouses that have been abandoned in funeral homes. He also helped create Manalapan’s veterans memorial.

But he never went back to Vietnam — until February.

Don't forget those who served: Veterans' cremains sat abandoned on funeral home shelves; then Shore vets stepped in

Back in Hanoi

To mark the 50th anniversary of their release, Drummond and five other former POWs spent three weeks touring the former South Vietnamese capital of Saigon, now known as Ho Chi Minh City, along with the Mekong River, the killing fields of Cambodia and Vietnam's capital, Hanoi.

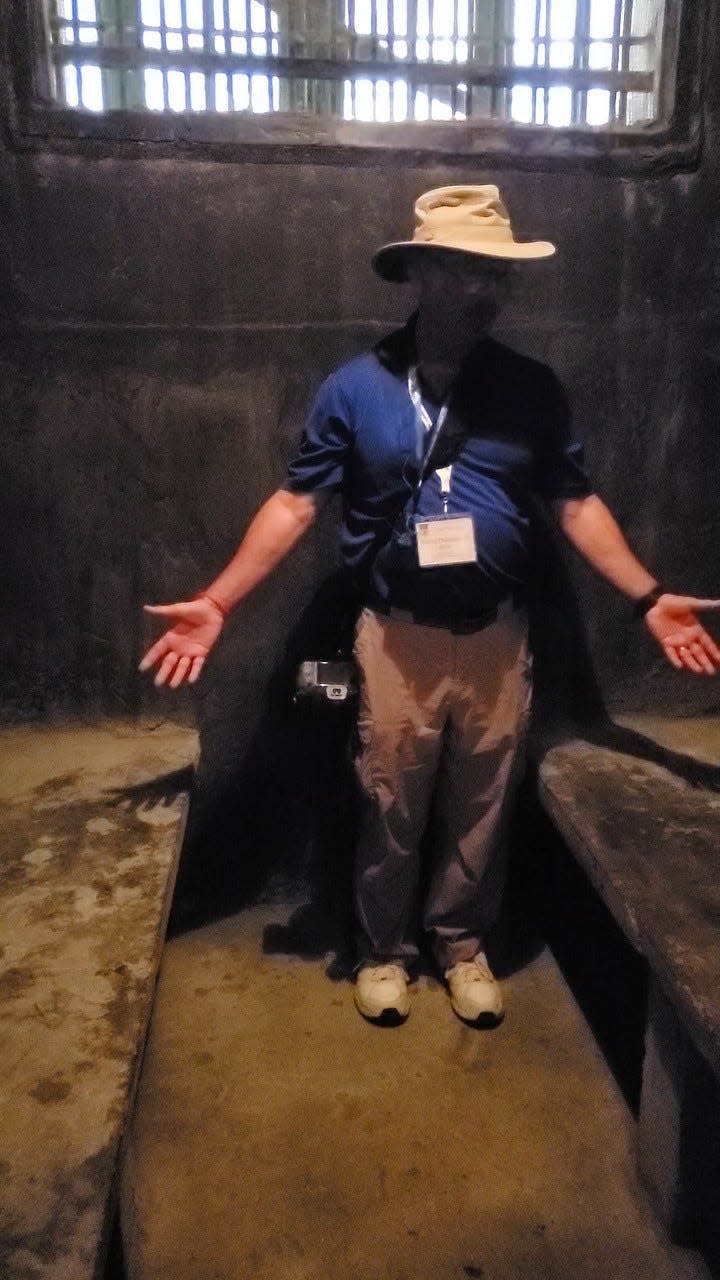

“Most of the Hanoi Hilton has been torn down; the front section is now a museum,” he explained. “The entranceway we were all dragged through is still there. The interrogation rooms and some of the holding cells — not the one I was in, but very similar — were still there.”

Telling his tale: His legs were blown off in Vietnam, but Brick veteran's story was not over

He walked into one of those rooms.

“It was somewhat unnerving and emotional,” he said. “I realized they weren’t going to lock the door; I was going to get out.”

His encounter with the former Viet Cong medic, arranged as part of the return, was “very warm and welcoming, which was a very big surprise.” The dinner with former enemy pilots struck a similar chord.

The whole journey was the pinnacle of a healing process that had been years in the making.

“It took a while, but I let go of hate,” he said. “I know there were people who did bad things. You just can’t hang onto this.”

That’s always been a theme of his presentation, but his return to Vietnam drives the point home.

“This rounds the story out,” he said. “This closes the loop.”

Jerry Carino is community columnist for the Asbury Park Press, focusing on the Jersey Shore’s interesting people, inspiring stories and pressing issues. Contact him at jcarino@gannettnj.com.

This article originally appeared on Asbury Park Press: Vietnam ex-POW from Manalapan teaches a new generation to drop hate