Eat like a local — have a California roll, a French dip and a Moscow mule, all invented in L.A.

Now here’s a new spin on “eating local” for you.

Supposing you were to pack a picnic for the Hollywood Bowl with exclusively created-in-L.A. foods.

What would be on your menu?

Appetizers

The California roll. Now, right off, there’s an argument over who invented it. Not where — it was definitely Los Angeles, but was it a restaurant in Little Tokyo in the 1960s, or one on Restaurant Row on La Cienega in 1979? Which is true? What, do I look like a judge?

Some make the case for chef Ichiro Mashita at Tokyo Kaikan, which opened in 1964. Others side with master sushi chef Ken Seusa at Kin Jo, which opened in mid-1979. Andrew F. Smith, author of “American Tuna: The Rise and Fall of an Improbable Food,” thinks Seusa is the “much more likely claimant.” Gourmet magazine’s speedy assessment of the new sushi, in 1980, suggests that’s the case, but there’s timing, and there’s adroit PR.

The inside-out roll is swaddled in rice and sesame seeds, around seaweed, avocado, cucumber and sometimes a scrap of crab (or imitation crab). You can probably buy it in gas-station deli cases these days, but back then it was a gourmet’s novelty, destined to be a world-beater, even though, 40 years ago, a New York Times restaurant critic, reviewing it at a Big Apple sushi spot, listed it among “misbegotten inventions.”

Salad

Let’s be frank with ourselves. Call something a “salad,” and it shushes the calorie conscience as effectively as duct tape on a mobster’s yap.

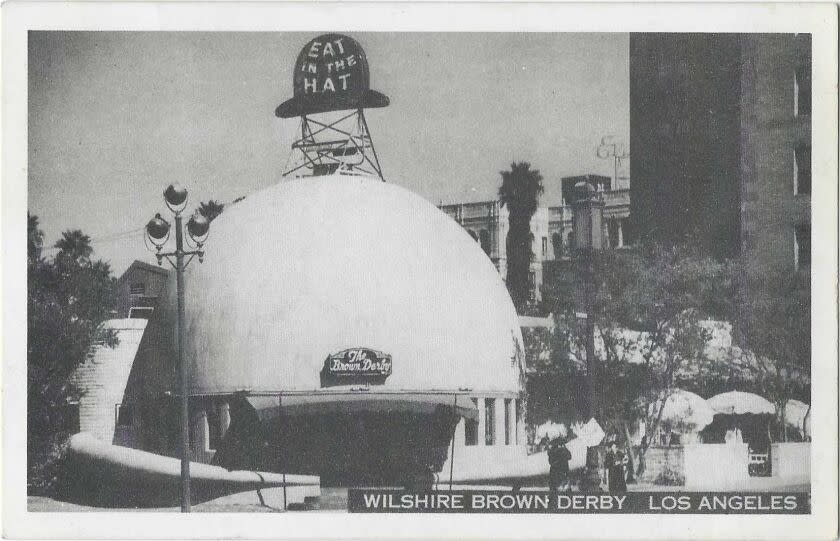

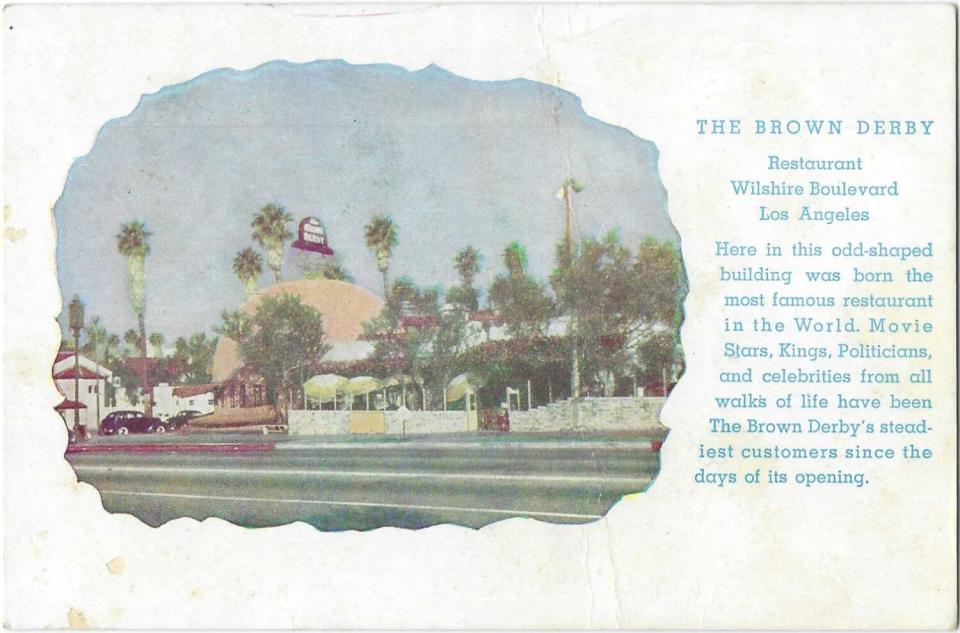

Take the Cobb salad, invented here at the renowned Brown Derby restaurant, the flagship of several Brown Derbys, not all of them in the hat-shaped architectural style called “programmatic,” like that donut-shaped donut store. (It was, as a legend goes — and really, legends are what we are dealing with here — built on a bet between one of Gloria Swanson’s ex-husbands and man-about-town Wilson Mizner, that “if you know anything about food, you can sell it out of a hat.”) The Cobb salad can feed you for an entire day and KO your cholesterol too — chicken, bacon, avocado, cheese, eggs, and oh-by-the-way lettuce.

The story goes that it was whipped up from a grab-bag of whatever happened to be in the restaurant refrigerator one day in 1937. A Brown Derby co-founder, Robert Cobb, adroitly ran both the Derby and its august clientele. (The Times acidly described him in 1941 as an “ex-barker from a Catalina Island [excursion] boat.”) Cobb shared the salad concoction with showman Sid Grauman, who, in hindsight, should have put the Derby chef’s mitts in cement outside his Chinese theater; it’s achieved greater renown than some of the stars.

The Caesar salad is closer to actual salad-ness in its lettuce-to-everything-else ratio. However, it was created in 1924 at Caesar’s Restaurante Bar in Tijuana, far from L.A.’s culinary penumbra. But the Chinese chicken salad, an early fusion dish, was evidently crafted at Madame Wu’s legendary Santa Monica restaurant. Actor Cary Grant came in one day in the 1960s raving about a salad he’d had elsewhere, and told Madame Wu she should do her own version. A recipe for it appeared in Sunset magazine in the early 1970s, and it is now a menu standard in restaurants that are as far from Chinese in theme as from China itself.

Entrees

Los Angeles, a city on the go from the get-go, came up with a lot of speedy, picnic-basket-worthy dishes.

The cheeseburger. Bring on your @s, ye cheeseburger pretenders. Since 1916, the Rite Spot, a fast-food place along the old Route 66, at Pasadena’s western border on Colorado Boulevard, had been run by the Sternberger family. In 1924, one Sternberger fils had inadvertently scorched a burger and covered up his grill goof with a slab of cheese. Alternate version: A customer asked for cheese on his burger. Instant sensation.

At about the same time, Ptomaine Tommy in Lincoln Heights was selling the “chili size,” a hamburger top-loaded with chili and sprinkled with chopped onions that in Ptomaine lingo were “violets” or “flowers.” Like many local businesses in the 1920s, Ptomaine Tommy fielded an employee baseball team, generating headlines like “Glendora in 5-to-1 Win Over Ptomaines.” The place closed in August 1958. A week later, its founder, Tommy de Forest, died. Our farthest-flung chili came from Chasen’s, the low-key, high-tab restaurant at Beverly and Doheny in West Hollywood. Chasen’s might be little remembered now, had not actress Elizabeth Taylor ordered Chasen’s chili airlifted to Italy, where she was shooting “Cleopatra.” The cost must have been at least a minor factor in the movie’s near-studio-bankrupting budget.

The burrito-as-fusion package is too diverse and diffuse for originator sleuthing, but the pastrami “kosher burrito” was sold for decades out of a joint on First Street in downtown Los Angeles, conveniently close to its patrons’ home bases, the LAPD headquarters and The Times’ photo staff quarters. I refused vehemently and repeatedly to try it, but I was assured that once tasted, it was never forgotten, which was probably because its gastric legacy stays with you forever.

The Tail o’ the Pup hotdog stand, another “programmatic” building that opened in 1946 and closed in 2005, is coming back soon — this time to West Hollywood — after a long spell in storage. Programmatic buildings like this are designed for a city living at automobile speed — you can tell even at 30 or 40 mph what the place is selling.

The durable Pink’s Hot Dogs opened as a pushcart on La Brea before the war, in 1939, and put up permanent walls in 1946. Full disclosure: Pink’s named its vegan hot dog after me. My original choice of topping, M&Ms, was deemed not suitable.

Extra hot dog points: Farmer John will be closing its Vernon slaughterhouse next year, and Dodger Dogs are now being made by Papa Cantella’s, which also sells them in stores. Actor, chef and discerning diner Vincent Price argued in his cookbook, though, that location can be a key ingredient: “No hot dog ever tastes as good as the ones at the ballpark [and] we have included Chavez Ravine … among our favorite eating places in the world.”

French dip sandwiches. Philippe the Original, up the street from Los Angeles’ Union Station, and Cole’s, the downtown restaurant and bar in what was once the Pacific Electric headquarters of the electric-streetcar empire, both opened in 1908.

As a vegetarian striving always for veganism, I have no stake in this epic dispute over which establishment invented the French dip sandwich, where the two cut faces of the sandwich roll are quick-dipped into the pan drippings of the meat of choice. Each lays claim to it. The Times’ 1960 obituary of Philippe Mathieu called him the “self-proclaimed father of the French dip sandwich,” and evidence tips in his favor — sorry, Cole’s. Philippe’s moved around downtown until 1951, when it settled into its edge-of-Chinatown spot. Cole’s has always been on 6th Street.

Desserts

The Brown Derby concocted a grapefruit cake that was, as they say, to die for. The cake part of the recipe mixes in a scant three tablespoons of grapefruit juice, but the cream cheese frosting commands grapefruit sections to be laid in layers between and atop the cake.

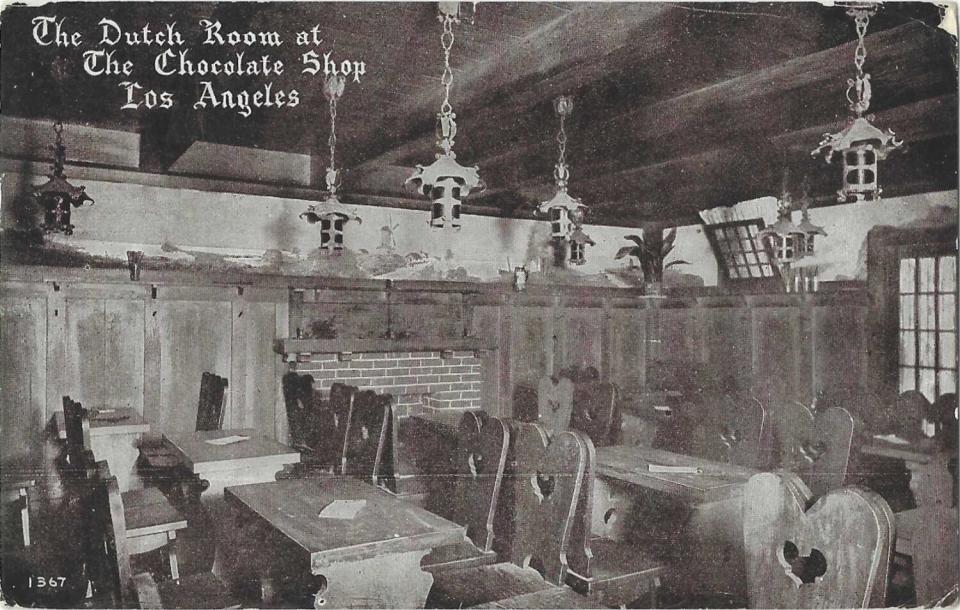

Hot fudge would be a picnicking challenge, but what an homage to C.C. Brown, creator of the hot fudge sundae. Clarence Clifton Brown hauled his candy-making equipment here from Ohio, and in 1906 opened a chocolate shop at the mercantile crossroads of 7th and Hill streets downtown. In 1929, his family moved the business to Hollywood, inaugurating its ice cream parlor just west of Grauman’s Chinese theater.

Sundae-making was a tableside performance, like guacamole or crepes suzette, served in a silvery metal bowl with your own personal pitcher of hot fudge. I had it once, a few years before the place closed in 1996, and it was so fearfully magical that I was afraid to go back; I couldn’t imagine that it could repeat, much less top, that one sublime sundae. I wasn’t far wrong. Rather than let some new owner despoil the hot fudge formula, the owners kept the secret original Brown recipe when they closed, and still sell jars of hot fudge online.

Fortune cookie. Again, its creation is as disputed a terrain as the Antarctic. Fortune cookies are the finale in Chinese restaurants, but they are Japanese by birth. Chefs in Japan created a version that is less sweet and more subtly flavored than the Americanized one. A San Francisco bakery called Benkyodo – which closed this year after 115 years in business — claims to have invented that one, using a purpose-built machine in 1911.

But three L.A. companies also staked out the same creation and same time-frame. The chief contender is the Fugetsu-Do sweet shop in Little Tokyo. Seiichi Kito co-founded the place in 1903 and slipped into each cookie a haiku, not a prognostication. The shop reopened after the U.S. imprisonment of L.A.’s Japanese population during World War II. Some friends and I stopped in for fortune cookies in the ‘90s on our way back to The Times from lunch. Mine read, “Something green is heading your way.” And wouldn’t you know it — a green van ran a red light and almost whacked me in the crosswalk. I’m a believer.

Mochi’s origin is undisputed. Frances Hashimoto, a formidable woman who helped to preserve Little Tokyo’s footprint and culture, also came up the inspiration for an ice cream ball inside a rice cake, and it’s become a menu and market staple. When you can find it in Trader Joe’s, you’ve entered the permanent food firmament.

Drinks

Los Angeles in the 19th century was the heart of wine-grape growing and winemaking in California, before subdivisions began to turn a bigger profit. A song about them, “The Wines of Los Angeles County,” in five verses, is referenced in my book about the Los Angeles River, and I will sing it at parties unless I am paid not to. Some vineyards still thrive here, mostly on hillsides in the Santa Monica Mountains.

Try to find one for your next Hollywood Bowl sojourn. Wine at the Bowl has a role, and it’s not just to drink. The signature sound of the Hollywood Bowl is not the 1812 Overture with fireworks. It is the suspenseful sound of an empty wine bottle, slowly rolling and clattering down tier after concrete tier, while Bowlers hold their breaths and wait for the smash finale.

As for hard liquor, the high-octane Zombie cocktail was the handiwork of Don the Beachcomber’s, which opened at its original Hollywood location in 1934. By 1938, as a Times advertisement shows, other restaurants were mixing and promoting their own versions of a Zombie.

There’s no real dispute, either, over the genesis of the Moscow mule, born at the Cock ’n’ Bull on the Beverly Hills end of the Sunset Strip. As the late Times food sachem Jonathan Gold wrote, it is “sneakily alcoholic.” The Cock ‘n’ Bull was GHQ for a postwar cocktail to get Americans to drink English ginger beer and Russian vodka. It was the formula of John G. Martin of Heublein, the big liquor interest, and Cock ‘n’ Bull’s English owner, Jack Morgan. By Christmas 1947, Bullock’s department store was advertising a set of four copper mugs for serving the Cock ‘n’ Bull’s Moscow mules.

If you’d like to pack a kick-less Los Angeles drink, make and take along an Orange Julius. It began as an orange juice stand downtown in 1926. One of its regulars was Willard Hamlin, the real estate man who found the location for vendor Julius Fried. But Hamlin had, as they said then, “a stomach,” and suggested that Fried put something in the orange juice to cut the acidity. After Hamlin died, at age 90, his daughter would let on only that a “pure food product” was the secret ingredient. It was probably powdered egg whites, added and whipped to a froth. Modern guesswork recipes suggest using milk or yogurt. One does wonder whether it would have prospered under the name “Orange Willard.”

Now, I would not like this to get around, but one thing Los Angeles lacks is a definitive L.A.-style pizza. We are, as always, ecumenical. You can crusade for any kind of pizza here without running the risk of heresy, as you would in, say, Chicago.

Alice Waters pioneered the California cuisine pizza, and Wolfgang Puck’s smoked salmon pizza at Spago laid down a defining marker. But now that all pizza is fusion, and people put anything on pizza dough and call it pizza, what can L.A. create that’s completely distinctive and unmistakably our own?

How about a pizza with chili orange marmalade, a nod to our citrus heritage, and julienned Dodger Dogs? Seriously — if you try it, let me know what you think. We’ll stake a claim and split the, uh, dough.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.