Ebola Outbreak in Sierra Leone Began at a Funeral

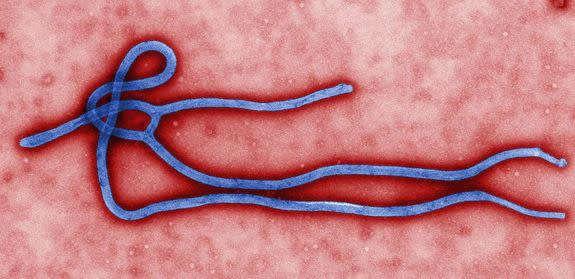

An extensive look at the genome of the Ebola virus reveals its behavior, when it arrived in West Africa and how it spread in the region to cause the largest-ever recorded Ebola outbreak.

Researchers sequenced 99 Ebola virus genomes from 78 patients in Sierra Leone, one of the countries affected by the outbreak that started in the neighboring Guinea, and found that the virus' genome changes quickly, including parts of the genome that are crucial for diagnostic tests to work.

"We've uncovered more than 300 genetic clues about what sets this outbreak apart from previous outbreaks," co-author Stephen Gire of Harvard said in a statement.

The first Ebola patient in Sierra Leone was identified in May. Investigations by the country's ministry of health traced the infection back to the funeral of a traditional healer who treated Ebola patients across the border in Guinea. The investigators found 13 additional cases of Ebola, all in women who attended the burial.

The researchers studied the viruses isolated from the blood of these patients, as well as subsequent Ebola patients, to identify the genetic characteristics of the Ebola virus responsible for this outbreak.

"Understanding how a virus is changing is critical knowledge for the development of diagnostics, vaccines and therapeutics, as they usually target specific parts of the viral genome that might change both between and within outbreaks," co-authors Kristian Andersen and Daniel Park of Harvard University told Live Science. [Ebola Virus: 5 Things You Should Know]

The findings suggest that the virus was brought to the region within the past decade, likely by an infected bat traveling from Central Africa. Earlier work had suggested the virus was circulating in animals in West Africa for several decades without having been detected.

The virus seems to have made a single jump from an animal to a person, and from there continued its journey through human-to-human transmission, the researchers said. This means that the current outbreak, at least in Sierra Leone, is not being fed by new transmissions from animals, in contrast to some previous Ebola outbreaks, which grew partly because of people's continuous exposure to infected animals.

This finding can guide decisions on whether to focus on human-to-human spread of the virus or on minimizing contact with animals, for example, by banning the consumption of bushmeat, the researchers said.

The study was published today (Aug. 28) in the journal Science.

Sierra Leone outbreak was traced to a funeral at the border

So far in the Ebola outbreak, 3,069 suspected and confirmed cases of infection and 1,552 deaths have been reported, according to the World Health Organization. The outbreak started in February 2014 in Guinea and then spread to Liberia, Nigeria and Sierra Leone. [Infographic: 2014 Ebola Outbreak]

The new study revealed that those first Ebola patients at the funeral were, in fact, infected by two distinct viruses.

"The thing that was most surprising was that two genetically different viruses were introduced into Sierra Leone at the same time, and likely through one event at a funeral," the researchers told Live Science.

Researchers were able to retrospectively look for the disease in blood samples and trace the trajectory of the virus because they were on the watch for another deadly disease, Lassa fever, said co-author Augustine Goba, director of the Lassa Laboratory at the Kenema Government Hospital. Goba was the doctor who identified the first Ebola case in Sierra Leone.

"We could thus identify cases and trace the Ebola virus spread as soon as it entered our country," Goba said.

Nearly 60 co-authors from several countries helped collect samples and analyze the genome of the virus. Five of them contracted Ebola in the course of their work in the epicenters of the outbreak and died from the disease before the publication of the study.

"There is an extraordinary battle still ahead, and we have lost many friends and colleagues already, like our good friend and colleague Dr. Humarr Khan, a co-senior author here," said co-senior author Pardis Sabeti, an associate professor at Harvard.

There are no vaccines to prevent infection with Ebola virus or drugs to cure the disease. An experimental treatment based on antibodies, called ZMapp, has shown promise in monkeys but it's unclear whether the drug is also effective in treating people.

Email Bahar Gholipour or follow her @alterwired. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Copyright 2014 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.