ECB Weighs Options to Limit Banks’ Gains From Crisis Loans

(Bloomberg) -- The European Central Bank is searching for ways to stop lenders from profiting unduly as it raises interest rates to combat record inflation.

Most Read from Bloomberg

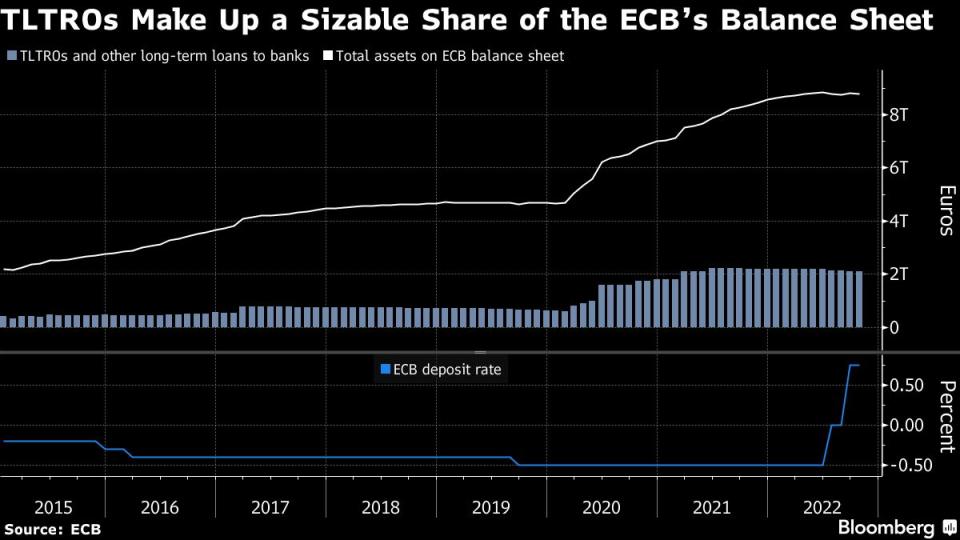

The issue concerns about €2.1 trillion ($2 trillion) of ultra-cheap loans, known as TLTROs, that were granted at the height of the pandemic to keep credit flowing and stave off deflation.

While the initiative was successful, it’s since become a thorn in the side of policymakers as banks can park the proceeds of the loans at the ECB and earn interest that exceeds their costs.

Doing so is becoming ever more lucrative as rates that were below zero as recently as July have risen to 0.75% and are expected to be doubled on Thursday. That may prompt the ECB to act when it meets this week.

Such risk-free profits for banks look bad at a time when Europe’s energy crisis is sending household heating bills soaring and prompting some firms to curb production. But there are policy implications too: the steady source of income discourages early repayments that would help officials fight inflation. Euro-zone central banks could also post losses.

Estimates for how much lenders are currently benefiting vary. Economists at Morgan Stanley reckon they could be getting additional stimulus of almost €28 billion.

President Christine Lagarde said last month that parts of the ECB’s remuneration mechanisms must be revisited and will be reviewed “in due course.” Since then, officials have narrowed the debate over surplus cash being held at the ECB to three options.

Tougher Loan Terms

Making the conditions on the TLTRO loans tougher has emerged as the favorite option.

Banks currently face interest equivalent to the average deposit rate over the life of the loan. The ECB could make this more expensive.

Changing contracts retroactively could pose legal challenges and jeopardize takeup at any future TLTRO offerings. But officials reckon those obstacles are surmountable because the case underpinning the agreements has vanished.

Indeed, credit to businesses is growing at almost 9% a year -- the fastest pace since 2009. That’s threatening to stoke inflation that, at just short of 10%, is already five times the ECB’s medium-term target.

With an early-repayment deadline days before the ECB Governing Council’s December policy meeting, officials may push for a solution this week. Officials have signaled that waiting until the bulk of the loans -- about €1.3 trillion -- expires in June 2023 isn’t an option.

‘Reverse Tiering’

Another way of reducing payments to banks would be to make some deposits subject to a lower rate of interest, or no interest at all.

Known as reverse tiering, that would be the opposite of a strategy the ECB used to ease pressure on banks after it introduced negative rates in 2014. But the approach could also bring “unforeseen market consequences,” according to economists at BNP Paribas.

They include pushing the rate that financial institutions charge each other to lend unsecured overnight further below the deposit rate as cash is pulled from ECB accounts and placed elsewhere. Excessive deviations between those two rates can impede how monetary policy is transmitted to the wider economy.

There could, too, be further strains for the short-term repurchase, or repo, lending market. The arrival of money from ECB accounts could exacerbate a situation whereby too much cash is chasing too little of the collateral needed for other financial operations.

Officials have expressed worries about money-market developments. Chief Economist Philip Lane has said the ECB would remain “attentive to the spread between different money-market rates as well as collateral scarcity concern.”

Reserve Management

The ECB could increase the level of minimum reserves it requires lenders to hold and lower the interest it pays on them.

Banks must currently keep 1% of certain liabilities, mainly customer deposits, at the ECB and receive interest equivalent to the main refinancing rate -- 1.25% at present.

While changing that arrangement doesn’t come with any legal issues either, it’s also the least effective of the ECB’s options. Doubling reserve requirements -- they used to be 2% until early 2012 -- would cover less than 16% of outstanding TLTRO loans.

--With assistance from Libby Cherry.

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

What the Alzheimer’s Drug Breakthrough Means for Other Diseases

The Private Jet That Took 100 Russians Away From Putin’s War

Female Bosses Face a New Bias: Employees Refusing to Work Overtime

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.