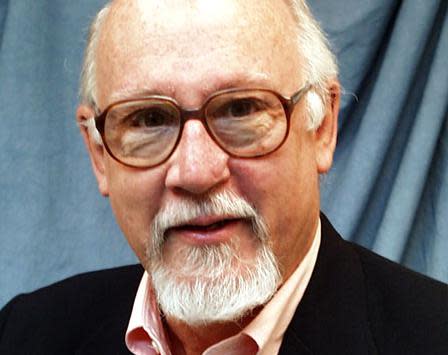

Ecologist advises people to pay attention to the world around us | DON NOBLE

Whit Gibbons, now retired, is one of America’s foremost ecologists with 25 books, 250 scientific publications and 100 encyclopedia articles. Newspapers everywhere carry his column ― 2,000 columns so far.

I had thought that “Salleyland” would be an autobiography, like E.O. Wilson’s “Naturalist,” but this was only partly the case.

Gibbons bought 35 acres near Salley, South Carolina, in 2008. He later bought 35 more acres and some friends bought 35 adjoining acres, so there is in a sense a hundred-acre wood.

This book is the story of how he has explored those acres: woods, a stream, a lot of swamp and wetlands and some sandhills, and made field notes, photographs, and even audio recordings of what he has found.

It is a kind of instruction manual, advice on how you might, and should, do the same even on suburban land or parks, or anywhere. The earth is teeming with plants and animals and he advocates looking carefully, making lists, learning what is all around you.

Nature is not simple. Gibbons writes: “Ecology is more complex than math, chemistry, or physics because the variables are virtually unending. People should say ‘it’s not ecology’ instead of ‘it’s not rocket science.’ Ecology, a subset of biology, has way more variables than any rocket launch.”

As he describes animals he found, it seems oddly true.

Of beetles, he tells us, there are 350,000 described species in the world, 30,000 in the U.S.

That’s a lot of beetles! He tells us there are 5 million species of fungi on earth, with only 100,000 identified and named.

Beavers are fun to watch but can flood places we want dry. Beaver dams have been found over 2,000 feet long.

Bats have tiny eyes and can see in the daytime.

Gibbons, a professional herpetologist, is especially fond of snakes. He has in fact taught his grandchildren to love them too. They can identify venomous snakes on sight and leave them alone but happily pick up many other species, even diving into the creek after them. That is a snake too far for most folk.

Of mushrooms, on the other hand, Gibbons is very cautious.

Eating a woodland mushroom you picked is inherently dangerous. He doesn’t do it. He passes on a professor joke. When asked about a particular mushroom, the biology prof says “Yes, you can eat any mushroom ― once.”

Gibbons is knowledgeable and unsentimental about the “red in tooth and claw” nature of nature.

In the wood duck boxes he sets out, the female may lay one egg a day, sometimes as many as 10. Then, if a big rat snake enters, she leaves, “passing the snake at the door.”

The rat snake will eat all the eggs and rest there for several days digesting them. The female wood duck, meanwhile, sets about laying eggs elsewhere.

The male wood duck has been standing by, should re-nesting be called for.

There are even stranger animal behaviors, too odd or complicated to relate here.

There are horsehair worms, sometimes 2 feet long, inside the stomach of a grasshopper.

And there is the pirate perch, a small fish who starts out life with his vent, cloaca, near the tail. But it migrates to just under the fish’s throat, just behind the gills. To find out why, and a lot of other odd things, read “Salleyland.”

It is engaging, pleasant, and therapeutic. Engaging with nature can lower blood pressure, increase the attention span of kids with ADHD, and help with memory and mood.

Aside from the mushrooms, there is no down side.

In his writing for a popular audience, Gibbons avoids controversy but obviously felt compelled to comment on the present-day study of biology in the academy.

Amateur biologists, list makers, observers and reporters are more valuable than ever, he tells us:

"Many college students, including those in graduate programs in biology, do not acquire field experience [because]... the academic institution itself de-emphasizes the importance of natural history. Many universities now follow a business model and are more supportive of biology departments that emphasize research in molecular biology and genetics because funding opportunities in these fields far exceed those of grants given for environmental studies. Disturbingly, many colleges have become so excessively litigation conscious that some professors are reluctant to risk an over-night trip bearing responsibility for a bunch of kids in their late teens or early twenties. I applaud all teachers who take their chances in giving students real-life experiences of the natural world."

Don Noble’s newest book is Alabama Noir, a collection of original stories by Winston Groom, Ace Atkins, Carolyn Haines, Brad Watson, and eleven other Alabama authors.

“Salleyland: Wildlife Adventures in Swamps, Sandhills, and Forests”

Author: Whit Gibbons

Publisher: University of Alabama Press

Pages: 166

Price: $22.95 (Paper)

This article originally appeared on The Tuscaloosa News: Pay attention to the world around us, ecologist advises | DON NOBLE