The Economist publishes seven maps exposing Putin's distorted historical claims

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Russian dictator Vladimir Putin has attempted to justify his full-scale invasion of Ukraine with pseudo-historical claims, asserting that Russians and Ukrainians are one people supposedly divided by "external forces," according to an "anti-Russian" plan.

Putin's claims that the formation of Ukraine as a separate state from Russia is the result of some external conspiracy imposed on Ukrainians against their will is "nonsense," writes The Economist in a Jan. 29 article, "A short history of Russia and Ukraine. Seven maps that illustrate Vladimir Putin’s distortion of history."

NV presents these maps and the key points from The Economist's commentary on them (click on the image to enlarge it).

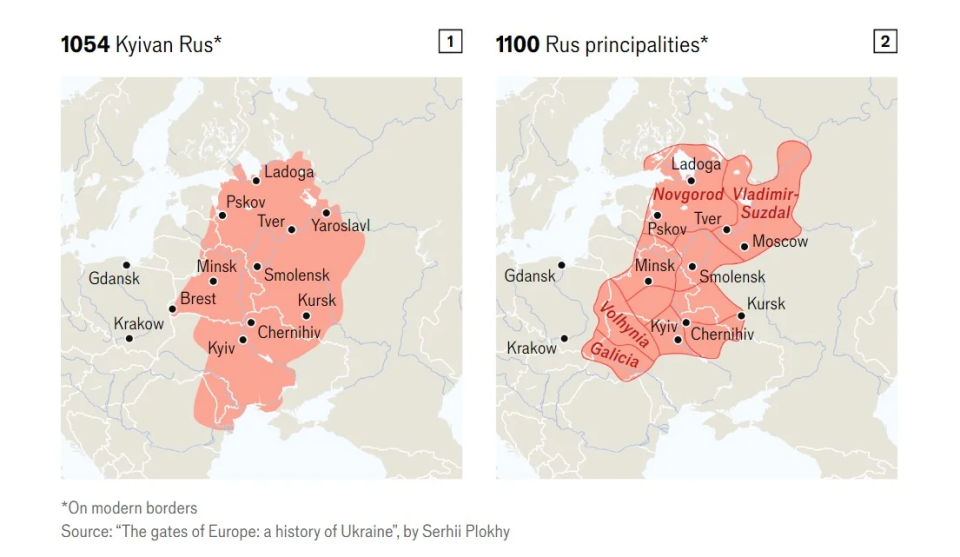

1-2. Kyivan Rus in 1054 and its fragmentation into principalities (map of 1110)

Putin loves to appeal to the times of Kyivan Rus’ — "a confederation of princedoms that lasted from the late 9th to the mid-13th century" — as the source of a supposedly shared "Russian-Ukrainian identity," The Economist writes. However, the center of Rus’ was Kyiv, the current capital of Ukraine. Although Kyivan Rus’ did encompass parts of the territory of present-day Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus, it began to fragment into semi-autonomous principalities by the mid-11th century (map 2). These included Halychyna and Volyn, which covered parts of modern Ukraine and Belarus, Novgorod, and Vladimir-Suzdal, in modern-day Russia. The Mongol Empire besieged Kyiv in 1040, finally destroying what remained of Kyivan Rus’ as a single entity.

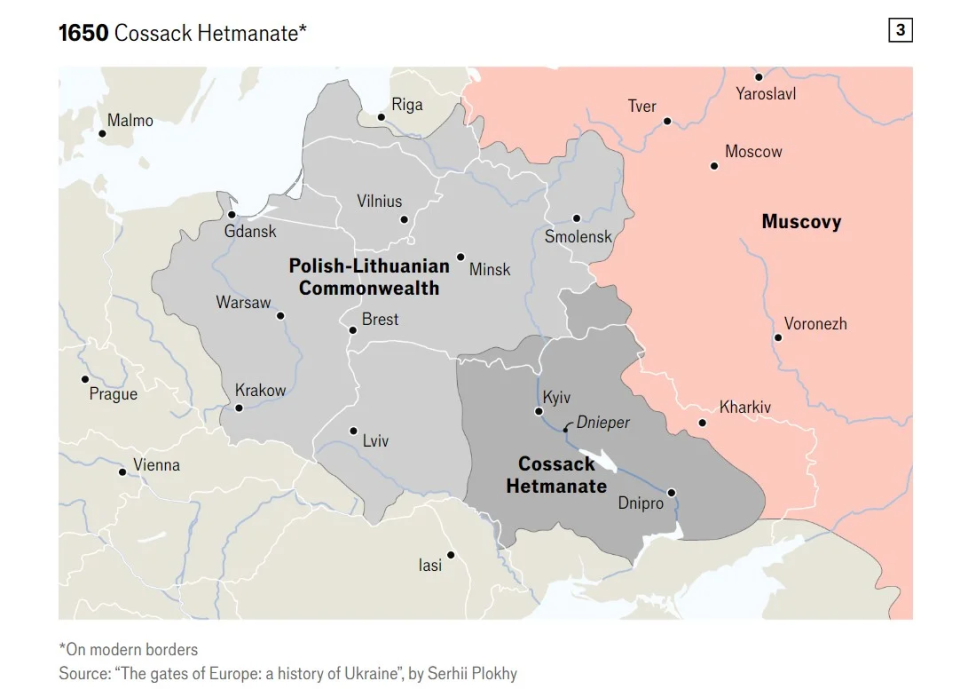

3. Hetmanate — Ukrainian Cossack state as of 1650

When the Mongol Empire and its successors (khanates), began to decline in the 14th century, rival polities rose to fill the vacuum, the article said.

"In the east of the region power eventually accumulated in Moscow, leading to the creation of the Grand Principality of Muscovy,” says the accompanying text to the maps.

“To the west, what had become the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania joined forces in 1569 to create the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth."

In 1648 the Cossacks, "settlers on the steppe who amalgamated into disciplined military units," as The Economist calls them — led an uprising against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. This led to the formation of their state, the Hetmanate (map 3), which many Ukrainians see as the origin of their identity as an independent state, the publication said, adding that Cossack lands were indeed often called "Ukraine."

Early Cossack warriors practiced a limited form of democracy, unlike the autocratic regime of Muscovy.

"That the Hetmanate came about as an act of resistance to larger neighboring powers is a history that resonates with Ukrainians today," The Economist writes.

“In the 19th century, the folk memory of the Cossacks’ state helped inspire the birth of a recognizable form of Ukraine’s cultural nationalism."

The 17th-century Cossack state went through troubled times. In 1654, threatened by the Poles as well as the Ottomans to the south, Cossack leaders pledged allegiance to the tsar of Muscovy. The Hetmanate’s territory had split into two by the 17th century: Muscovy took control of the east bank of the Dnipro River, and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth seized the west. In 1708 Ivan Mazepa, a Cossack leader, led a failed uprising against Tsar Peter the Great, who became the first Russian emperor in 1721. Russia still considers Mazepa a traitor while in Ukraine he is a hero.

Read also: The Putin interview showed weakness

4. Maximum extent of the Russian Empire as of 1914

The Russian Empire broke up the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, with help from Austria and Prussia in the late 18th century. The Russians also seized territory from the Ottoman Empire in the south of modern-day Ukraine, including Crimea, which was annexed by the Russian Empress Catherine the Great in 1783. She oversaw the final dismantling of the Cossack Hetmanate.

On the eve of World War I the Russian Empire stretched from the Sea of Japan to the Baltic (map 4).

5. 1922-1989: Soviet expansion into Eastern Europe

Weakened by World War I, the Russian Empire experienced two revolutions in 1017. The first overthrew the Romanov dynasty, the second brought Vladimir Lenin and his Bolsheviks to power. Officials in Kyiv founded the Ukrainian People’s Republic (UPR) — first as an autonomous state, and in January 1918 as an independent state. Eventually, it was captured by Lenin's troops, but, as The Economist writes, "the strength of Ukrainian national identity compelled him to create a socialist Ukrainian republic, and to allow the use of the Ukrainian language." In 1922 Ukraine became one of the four founding members of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) — or Soviet Union.

Under the Molotov-Ribbentrop non-aggression pact, which the Soviet Union signed with Nazi Germany in 1939, the two countries carved up Eastern Europe. Parts of Poland inhabited by Ukrainians later were annexed to Soviet Ukraine. The Soviet Union transferred control of Crimea from Soviet Russia to Ukraine in 1954.

Read also: Putin’s lies go unchecked by American propagandist Tucker Carlson

Ukraine, as part of the USSR, suffered enormous hardships, The Economist writes: among them the Holodomor-genocide of the 1930s, as well as the events of the mid-20th century. Then, as American historian Timothy Snyder wrote in his book, Ukraine became part of the "bloodlands" between Hitler and Stalin — referring to the territories of Europe where the Nazi and Soviet regimes committed mass violence on an unprecedented scale between 1933 and 1945.

"Co-operation between some Ukrainian nationalists and the Nazis during the war is used by Mr.Putin as evidence for his claim that the Ukraine of today is run by fascists," The Economist said.

In 1986, in the last years of the Soviet Union, the Chornobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine suffered the worst nuclear accident in the world. The damage, and the ensuing cover-up, heightened Ukrainians’ anger towards the Kremlin, the article said.

6. Fall of the Soviet Union: 1991

In the 1980s, Mikhail Gorbachev, the last Soviet leader, tried to reform the Soviet Union by embarking on a path of glasnost’ and perestroika. The Eastern European states, which were under Soviet control through the framework of the Warsaw Pact, took the opportunity to demand their freedom. The Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, bringing independence to its 15 constituent republics (map 6). Putin considers this "the biggest geopolitical tragedy of the 20th century," The Economist said.

Ukraine suddenly became home to the world’s third-largest nuclear arsenal after the collapse of the USSR. In 1994, it agreed to denuclearize in exchange for security assurances from the United States, United Kingdom, and Russia. Ukraine used this agreement, known as the Budapest Memorandum, to ask the U.S. and UK for aid on the eve of Russia’s invasion in 2022.

7. Russia's war against Ukraine: 2014–present

The Orange Revolution of 2004 highlighted Ukraine's democratic ambitions. Thousands of people protested against a rigged presidential election that gave victory to a pro-Russian candidate Viktor Yanukovych.

“Ukraine’s democratic resolve was even more visible during the ‘Maidan revolution’ (Revolution of Dignity) in 2013-14,” The Economist said.

It was a reaction to Yanukovych's refusal to sign an association agreement (an extensive free-trade deal) with the European Union. Thousands of Ukrainians took to the streets; Yanukovych fled to Russia. The new Ukrainian government succeeded in signing the agreement with the EU, “infuriating Mr. Putin,” the publication wrote.

His response to Maidan marked Russia’s first military incursions into independent Ukraine. In 2014 the Kremlin illegally annexed Crimea and sent troops into the Donbas (map 7). Russia’s separatist proxies — led by Russian intelligence officers — declared so-called "people's republics" in Donetsk and Luhansk. By December 2021, just before Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022, a total of over 14,000 people had been killed as a result of the previous phase of the war.

The war continues.

We’re bringing the voice of Ukraine to the world. Support us with a one-time donation, or become a Patron!

Read the original article on The New Voice of Ukraine