Edith Halpert and American Modernism

Edith Halpert and the Rise of American Art is now at the Jewish Museum. If there’s a show to see in New York, it’s this one. It’s beautifully done, as are all the Jewish Museum’s shows, with great art and a majestic personality at its center. Halpert (1900–1970) was self-made, tough, kind, focused on the next buck, a charming woman with a canny sense for under-the-radar art. She took trompe l’oeil gun paintings, old weather vanes, American cubism, and Georgia O’Keeffe and made an American whole. As a young woman, at the start of the Depression, she opened the cutting-edge Downtown Gallery, which represented Stuart Davis, Charles Sheeler, and Jacob Lawrence through thick and thin.

Through thick and thin. That’s the life of an art dealer. The best are tastemakers and connoisseurs. In supporting living artists, they’re philanthropists invested in the riskiest propositions. They’ve built careers and collections, and until the 1970s, dealers pumped the blood through the living and breathing American art corpus.

The Halpert show builds an intellectual, biographical, and aesthetic storyline. It starts with a voyage and with romance. Edith was born in Odessa, coming to America in 1906 with her family after a pogrom but with backup cash. Never poor, Edith took art lessons and married Samuel Halpert, a not-so-bad artist who situated his young wife in a jostling art ambiance she grew to love — the New York world of the Ashcan artists, the Eight, Stieglitz, but also the dregs of American impressionism, massive social disruption, and the chance for artists to say something new. Edith, as she said, “married American art.”

That’s part of Edith’s story. Here, the exhibition and the catalogue are at their best. The book is a biography, and the two work in satisfying tandem. In 1920, Edith got a job at the investment company S.W. Straus as an efficiency expert. She was a pioneer in introducing Dictaphones and in soundproofing offices loaded with clanging typewriters. She was also in charge of advertising. By 1925, she was on the Straus board, making $6,000 a year. Around 1930, there was Edith, the dame with brains, versus not-so-bad artist Sam, whose death from meningitis came weeks after their divorce.

Edith Halpert was free to pursue her vision, and her business plan. The business of selling art in 1930 was set in Midtown, or in London and Paris. Halpert placed her business downtown, at 113 W. 13th Street. It was cheaper space and signaled, “I’m not playing in the usual ballpark.”

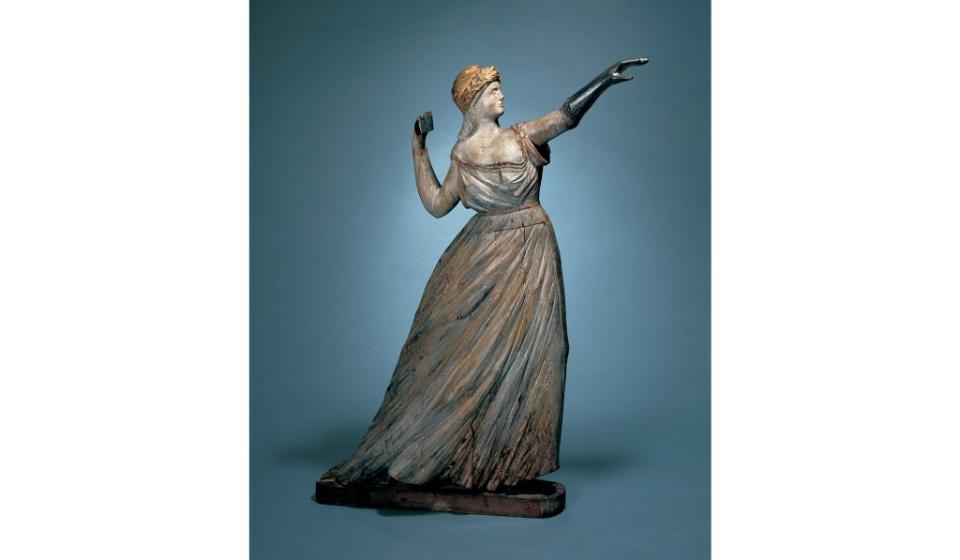

It wasn’t paycheck-by-paycheck, but it wasn’t easy. Halpert read her buyers well, moving from swell to ebb to swell. Her anchor in the 1930s was Rockefeller. John D. Rockefeller’s wife kept the Downtown Gallery going through her purchases of folk art, some new American art, and side deals. Halpert sometimes bought European things for her and got a cut. American folk art — paintings by itinerant artists, old signs, weather vanes, ship figureheads — was new to the art market. This material obliged a 1920s avant-garde aesthetic — angular, abstract forms, a simple palette, no fancy flashes like impasto, and simple subject matter. Halpert found the material in barns and antique shops throughout rural New England, buying it for next to nothing and then fixing a New York price — always add three zeros — and selling it to Rockefeller.

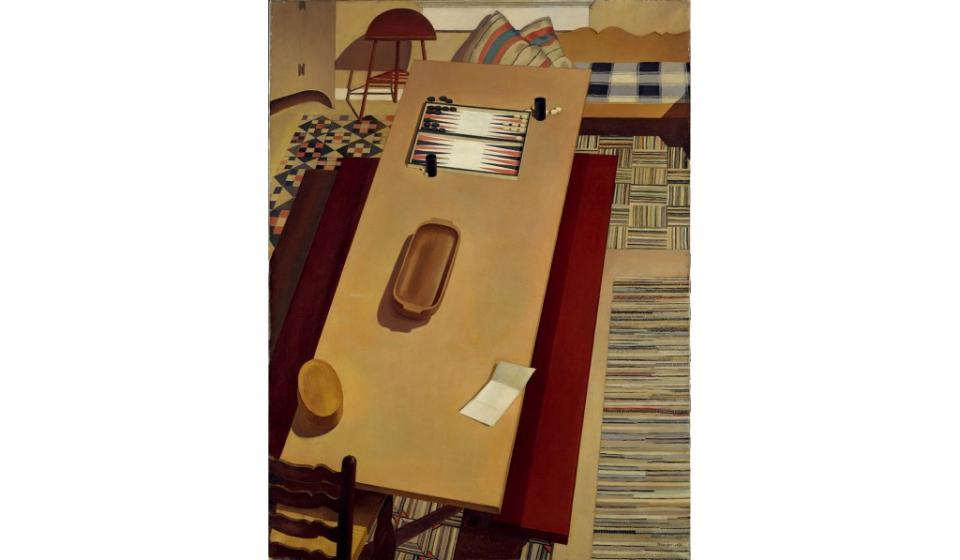

This was a cash cow. At the same time, Halpert represented Charles Sheeler. Home Sweet Home and Americana, both from 1931 and shown by Halpert, echo the simple geometric patterns and shapes of American Shaker folk art. Sheeler and Halpert found a formula merging abstraction and realism and making it sell. Another artist, Elie Nadelman, did the same with sculpture. Halpert was a good brander, and part of her brand was uniting folk art from the 19th century with the art of her day. With another early artist, Stuart Davis, Halpert was less successful. Using profits from her folk-art sales to a Rockefeller or two, she was able to subsidize Davis during much of the Depression. Halpert, as part of her business model, kept her stable of living artists at a dozen or so. She represented Arthur Dove, Georgia O’Keeffe, and John Marin when they were already famous. Davis left and came back.

The show markets Halpert as a trailblazing woman facing a bad bunch of old dudes, but it’s a more nuanced story. In the 1920s and 1930s, purchases of American avant-garde art came mostly from women such as Rockefeller, Lizzie Bliss, and Mary Sullivan. Halpert made the most of it and set up women’s art-buying clubs. I suspect she was the daughter they wished they’d had, and men didn’t mind getting guidance from a female dealer. Women, they thought, instinctively understood art. Halpert was not the only prominent dealer who was a woman. One of her competitors, Kraushaar Galleries, was run by women. By the 1940s, Betty Parsons and Peggy Guggenheim were important and respected.

Aside from Jacob Lawrence and Horace Pippin, who is a high-end, decorative folk artist, Halpert pierced no race boundaries. Ben Shahn, another of her artists, painted Sacco and Vanzetti pictures, and they’re yawns. That said, Shahn’s Hunger, from 1946, is in the show, and it’s a good picture. It’s left-wing Rockwell, though, and minor. One of Halpert’s best clients in the 1950s was Bill Lane, who owned a widget factory in Leominster, Mass. He focused on Sheeler and Davis, and Halpert made lots of money from him. By that time, Halpert’s artists had a quaint, cozy feel.

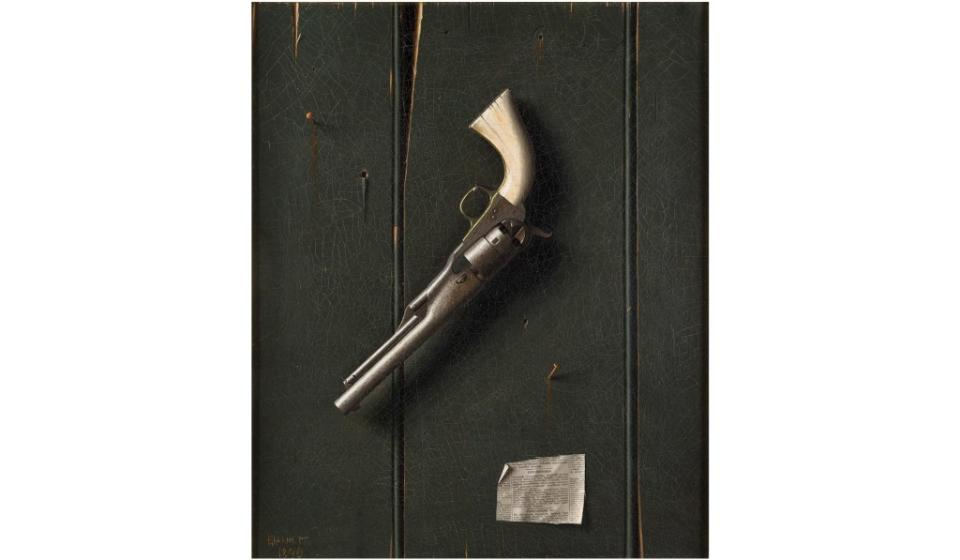

Edith Halpert and the Rise of American Art has to be marketed, I suppose, and the Jewish Museum markets her as a pioneer woman. I’d rather look at her business model and its relevance today. In the 1930s, “it was folk art that saved the gallery,” Halpert said. By the 1940s, the rich old ladies had moved on. By then, William Harnett “was the biggest sugar daddy I ever had,” Halpert recalled. She always drew from the grave to keep the living going. Influxes here and there of big money helped her support Davis, Lawrence, and Shahn. Halpert also had a small stable of living artists. One pot subsidized another.

She was the pivotal figure in reviving the market for trompe l’oeil American painting, too, and The Faithful Colt, by Harnett, done in 1890, is a star in the show. Halpert sold it in 1935 to the Wadsworth Atheneum in Connecticut. Work by Harnett and John Peto is dark and sulky. There’s a film noir quality about these artists, simple, disheveled scenes with steam hissing out of them.

Halpert was an art impresario, and discovering Harnett and Peto in the 1940s puts her on a parallel track with the Hollywood potentates who discovered Robert Mitchum, Lana Turner, and John Garfield. Bear with me. I look at Halpert as a peer of the Hollywood movie moguls like Lewis Mayer, Jack Warner, and Sam Goldwyn. Jewish, Russian, and an émigré, she was an outsider. Like millions, she became as devout an American as anyone, but she saw things that Americans didn’t see in themselves or took for granted. She promoted folk art, selling it as an honest, direct expression of everyday experience, practical like a weather vane but with no airs. She saw it as fine native expression, looking at it with fresh eyes. She saw good American quality in things most Americans saw as junk. And she restored these things to a place of pride. Harnett, Peto, and the other American trompe l’oeil painters had been overlooked, and she found a niche for them. As a bonus, these artists were long dead, so she didn’t have to share a commission with them.

Halpert’s taste wasn’t radical. Her artists were mostly representational. She left the abstract expressionists and pop art to others. I can’t imagine her navigating anything beyond 1970. She sold advanced art dealing consciously with social traps but safely bourgeois.

She deplored regimentation — a European trait — and was open to the point of looseness. Walking through the show, I felt many delightful jolts. Thank you, Jewish Museum curators, for making so many fun juxtapositions. Her taste was democratic and certainly not snobbish. The Liberty Weathervane Pattern, from 1879, from the Shelburne Museum in Vermont, looks great near Stuart Davis’s Little Giant Life, from 1950. Halpert marketed her late Davis works as the logical conclusion to eye-grabbing American signs and ship models from the 19th century. She was a great storyteller.

Halpert took American art on the road. In her day, the big museums rarely did American contemporary art shows. The dealers did them, and no one did them with more flair than Halpert. The difference was that Halpert took her shows to places like Wichita and Kansas City, where there was money and hunger for American art and an unpicked market that snobbier dealers wouldn’t approach.

In 1959, Halpert took her show back where she began. In 1959, she was a curator of the American art section of the vast American National Exhibition in Moscow. At that exhibition, Nixon and Khrushchev engaged in the famous Kitchen Debate — not in Halpert’s space but in spaces filled with General Electric appliances. In her Moscow gallery, one-third of the artists came from the Downtown Gallery. Nixon skipped her gallery — the art was too edgy — but Halpert was already a grande dame.

Accessibility was part of Halpert’s marketing plan. The Downtown Gallery was a space with home-sized rooms mixed with books, paintings, sculptures, and easy chairs. It was inviting and domestic. Halpert had multiple clients, among them the Rockefellers but also middle-class buyers. “I had to attract clients with ideas,” she said. “You know, if you advertised art for Christmas, nobody ever thought of giving art for Christmas.” She offered Christmas selections and post-Christmas sales, prints by Rockwell Kent, Thomas Hart Benton, Davis, Gorky, and even Edward Hopper (if you were after a Not-Very-Merry-Christmas vibe). Halpert worked with Macy’s to sell clothes and jewelry inspired by Sheeler and Davis. She offered installment plans to pay for art. She priced to sell.

In 1954, Halpert commissioned ABC for Collectors of American Contemporary Art, a beginner’s guide illustrated by Saul Steinberg to support its light touch. It encouraged people to buy for pleasure, not prestige or investment — supremely good advice — but also to buy American art, “simply because it is closest to our own lives.” In the mid-Thirties, Halpert, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, and the Rockefeller family organized big contemporary art shows in the new Rockefeller Center skyscraper as a way to draw people to the untenanted buildings. As hard as it is to believe now, these spaces weren’t hot prospects. La Guardia and Halpert wanted to push Manhattan as an art capital for people of modest means.

Halpert was a visionary and entrepreneur but also one-woman show. In the late 1960s, suffering from early-stage dementia, she tried to place her personal collection as a bequest to the Corcoran Gallery and the Smithsonian Institution in Washington.

An immigrant and an ardent American, she wanted the things she loved in public collections in the country’s capital. She also knew her contemporary art would spur the stodgy Washington establishment to look beyond portraits and Hudson River art to see the vibrancy and expansiveness of American art in its present.

“If that’s art,” Harry Truman said of a show she once organized, “I’m a Hottentot.” Did that sting enough for Halpert to want her own collection in Washington? As her health worsened, the deal collapsed. When she died in 1970, she had no succession plan. Her 1973 estate sale established Georgia O’Keefe’s Poppies as the highest-priced painting by a living American artist to sell at auction. Her work by Nadelman, Edward Hicks, and Yasuo Kuniyoshi also hit world records. Fittingly, the folk art that the estate sold did well. Folk art had, after all, commercially carried the Downtown Gallery for years.

The Jewish Museum’s galleries are elegant, but the building was a Warburg mansion. It feels like a home, a very grand home, but it’s easy to take possession. The curators evoked the warm, domestic feel of the Downtown Gallery, a good choice since Halpert sold art to love and cherish. No surprise to me. The museum always does great shows. Its Florine Stettheimer retrospective last year was a joy. Its curatorial vision is the best, and, remember, it’s not a religious museum. It follows the golden thread of Jewish culture wherever it goes.