Editorial: Facebook is contorting itself to accommodate Trump's abuse

Last week, a few hours after accusing "Big Tech" companies of censoring conservatives, President Trump put out an incendiary comment on Twitter and Facebook that seemed designed to bait them into censoring him.

Twitter did, albeit in a halfhearted way that didn't actually remove Trump's words. Facebook didn't — and its failure to act may do more harm to its cause than Twitter's display of backbone.

That's because Facebook's fecklessness will only feed into the mounting pressure on policymakers to regulate how social media networks police themselves, and to deny them a crucial liability shield if they fail to meet some new government standard for evenhandedness. Both of those options are fraught with unintended consequences and potentially bad outcomes.

Trump himself is one of the leading proponents of regulating social media. The misbegotten executive order he released Thursday (which drew a lawsuit Tuesday from the tech advocacy group the Center for Democracy and Technology) seeks to have the Federal Communications Commission and the Federal Trade Commission determine when those companies are misleading the public about their policies toward speech and concealing some kind of bias.

Later that day, Trump tweeted and posted a 102-word attack on Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey, saying he needed to get his city "under control" or Trump would send in the military. "Any difficulty and we will assume control but, when the looting starts, the shooting starts," Trump wrote, quoting (consciously or not) a racist and brutal Miami police chief from 1967.

Although Trump later contended that he was trying to warn people about the consequences of looting, his original words run clearly afoul of both social media companies' guidelines against glorifying or inciting violence. Twitter responded by hiding the tweet behind a notice that Trump's words had violated the company's rules, forcing anyone who wanted to read the tweet to click on the link provided. Facebook responded by ... doing nothing, despite calls from inside and outside the company to take the comment down.

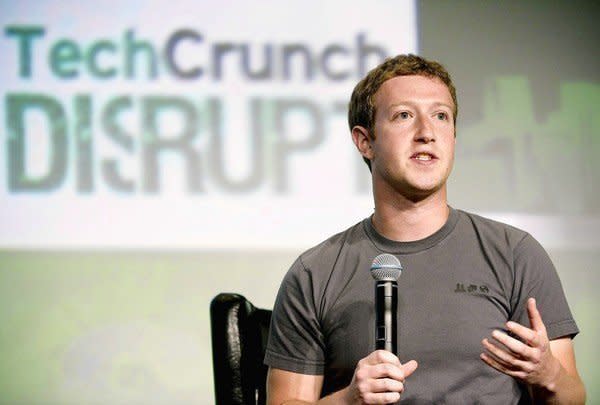

Facebook Chief Executive Mark Zuckerberg later explained that "although the post had a troubling historical reference, we decided to leave it up because the National Guard references meant we read it as a warning about state action, and we think people need to know if the government is planning to deploy force." He stood by that decision even as hundreds of Facebook employees protested — apparently the first time the company has witnessed such a large-scale action — and some of the country's most prominent civil rights leaders pressed him to change his mind. The employee revolt continued Tuesday, still to no avail.

Granted, moderating the torrential flow of content on a site as popular as Facebook is a huge challenge, which in itself is a good argument against sites growing to Facebook's scale. And there's necessarily some subjectivity involved. But lax moderation led Facebook to become a hotbed for fakery, hate speech and other damaging uses of the network. It has responded with some better rules and procedures, but they're meaningless if they're not enforced.

The more exceptions Zuckerberg carves out for powerful people, the more inconsistent and ineffective his rules will appear — boosting the case for orders like Trump's, which would give political appointees the power to shape how social media companies compete. And maybe Zuckerberg is comfortable with that idea, considering that he can afford the lawyers and lobbyists needed to navigate the new environment while upstart competitors cannot. But no one else should want that outcome.

Washington would be far better off focusing on ways to protect Facebook users and their privacy, particularly from the manipulation that the company empowers its advertisers to do by exploiting their personal information. Lawmakers, including Rep. Anna G. Eshoo (D-Menlo Park) and Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), have introduced bills to stop Facebook and its ilk from micro-targeting political ads without users' permission, preventing campaigns from tailoring their messages to play on the susceptibilities of small groups in ways that avoid detection.

But Congress has been just as leery of protecting internet users' privacy as Zuckerberg has been of enforcing Facebook's rules against Trump. They both need to change course.