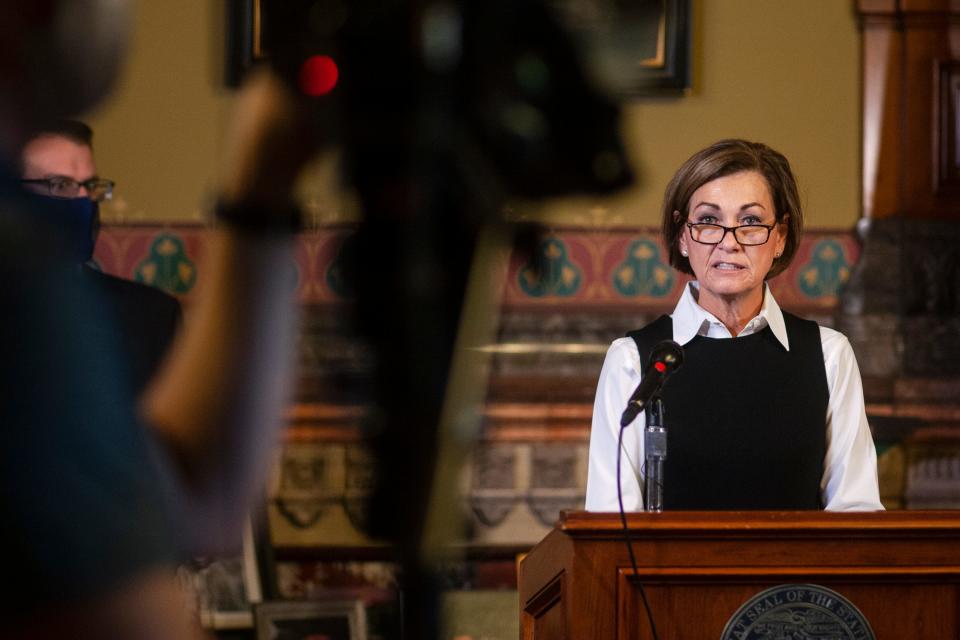

Editorial: Kim Reynolds kept Iowans in the dark. It was wrong, and violates the law.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The Iowa Legislature was explicit in 1967: “Free and open examination of public records is generally in the public interest, even though such examination may cause inconvenience or embarrassment to public officials or others.”

In 56 years since, a great many public officials have ignored this premise. But the Iowa Supreme Court has shown in a pair of opinions this term that it got the message, and the state will be better for it.

This decision fell to the Supreme Court because defiance of the 1967 law’s spirit is easy to find. The governor’s office has frustrated requests by declining to even answer them. Agencies at all levels have conditioned their compliance on Iowans paying exorbitant six-figure review fees. The law started with 11 exceptions for maintaining confidentiality, but subsequent legislatures have added on average over one new exception every year. Judgments of the Iowa Public Information Board often seem to turn on its head the original idea — presuming public access at the outset — and err on the side of privacy, deferring to discretionary decisions against disclosure.

In the two lawsuits against the state decided this year, the allegations were egregious (and state lawyers disputed only a few of them).

For months on end, Gov. Kim Reynolds’ office all but ignored eight straightforward requests from Bleeding Heartland and Iowa Capital Dispatch journalists and the Iowa Freedom of Information Council. When the organizations and journalists sued, some of the records were, magically, provided.

Polly Carver-Kimm fulfilled public information requests for years as part of her job with the Iowa Department of Public Health. She says that the responsibility was taken away from her in stages as she butted heads with superiors and Reynolds' staffers for being prompt and helpful in her work at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. She eventually resigned and sued for wrongful discharge.

State had argued that timeliness doesn’t matter

The Iowa Attorney General’s Office took some big swings to try to swat down the lawsuits. It argued that Iowa Code Chapter 22, the public records law, does not require timely compliance and that, even if it did, Reynolds’ staff was exempt. It argued that the public interest in upholding transparency laws wasn’t a good enough reason to bar officials from firing employees for complying with those laws. But district judges and Supreme Court majorities found instead that there are consequences for trying to shield the public’s eyes from the public’s business.

More: After Iowa Supreme Court rebuke, Kim Reynolds settles open records lawsuits for $175,000

Especially in the case directly addressing how the governor’s office dealt with requests, a ruling favoring state government would have tragically undermined Iowans’ practical ability to know about representatives’ work beyond their public, often self-serving pronouncements. The 6-0 decision dismisses the fiction that only explicit and ongoing refusal to share records breaks the law: “We conclude that a defendant may ‘refuse’ either by (1) stating that it won’t produce records, or (2) showing that it won’t produce records,” wrote Justice David May.

The other case was closer: A 4-3 ruling lets Carver-Kimm continue pursuing her wrongful-discharge claim, but only against her departmental superiors, not against Reynolds or her deputies. Whether or not Carver-Kimm ultimately prevails, it’s refreshing that four justices found her transparency-related arguments about public policy more compelling than the well-established principle that most employees in Iowa can legally be dismissed for any or for no reason.

Justice Matthew McDermott correctly observed: “What if, for instance, a lawful custodian is told by their boss that if they produce some embarrassing records, they’ll be fired? Without legal protection for the custodian in this circumstance, it’s likely that the records will never be produced — and the records’ existence will never be known to the requesting party.”

Few duties are of more critical importance than informing the public

Among the duties of every public official, few are higher than providing accurate information to the people. Iowans entrusted with this responsibility should review these court decisions and act accordingly, with prompt and candid responses to requests for records. In doing so, they will deliver insight to Iowans, to which state law entitles them. And they will avoid taxpayer expense for unnecessary litigation — double expense in some cases, The State Appeal Board last month approved paying about $135,000 to the journalists’ lawyers as part of a settlement agreement.

“The governor's office has stated it has revisited its open records policies and has committed to doing better moving forward,” Thomas Story, an American Civil Liberties Union of Iowa attorney, said during a news conference. “For our clients and us, this settlement agreement is about ensuring that it indeed will.”

Public records illuminate how decisions are made, far more than the carefully edited and stage-managed declarations shared at news conferences and in news releases. Legislators in the 1960s recognized and codified that the people have every interest in how they’re being governed and the right to find out. Or, as was declared almost 250 years ago this month, “Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

FURTHER READING: History and background of Iowa's open government laws

— Lucas Grundmeier on behalf of the Register’s editorial board

P.S.: Keeping public out of meetings also ends poorly for elected officials

Iowa's open meetings law, the companion to the open records law, serves the similarly important purpose of allowing any Iowan to be present where their representatives are considering or taking action, with carefully defined exceptions.

The Iowa Freedom of Information Council and local news organizations won a victory on this front by securing a settlement with the Bettendorf school board in which its members admitted illegally banning reporters from a public meeting last year.

About 300 people met in May 2022 to talk about misbehavior at a middle school. All but one school board member was present. Unfortunately, as Freedom of Information Council Executive Director Randy Evans wrote in a column, the district rebuffed complaints that day and afterward, and the Iowa Public Information Board “swallowed hook, line and sinker a laughable claim by school attorneys that school board members were at the gathering only as interested citizens.”

A lawsuit and the settlement followed. Bettendorf’s schools join the list of public agencies, such as the Warren County Board of Supervisors, whose attempts to evade the public meetings law have ended in embarrassment.

This editorial is the opinion of the Des Moines Register's editorial board: Carol Hunter, executive editor; Lucas Grundmeier, opinion editor; Rachelle Chase, opinion columnist; and Richard Doak and Rox Laird, editorial board members.

Want more opinions? Read other perspectives with our free newsletter, follow us on Facebook or visit us at DesMoinesRegister.com/opinion. Respond to any opinion by submitting a Letter to the Editor at DesMoinesRegister.com/letters.

This article originally appeared on Des Moines Register: Opinion: Kim Reynolds kept Iowans in the dark. That was wrong.