Editorial: When will we live up to our Declaration of Independence?

Protests against police violence and anti-Black racism over the last six weeks have been eye-opening for many white Americans who, if they contemplated what life is like in this country for people of color, thought of it primarily in the abstract. The jarring video of a white police officer pinning a Black man to the ground as he pleaded "I can't breathe," and then went still as life left him, made the abstract all too real. What the nation saw was the unsanctioned and extrajudicial execution of a Black man by a uniformed agent of the government.

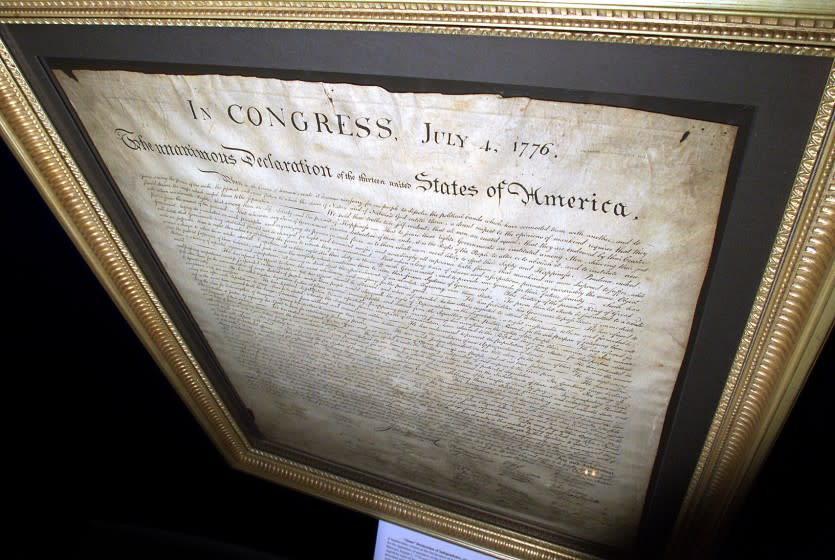

On Saturday the nation celebrates our Declaration of Independence, a document that has in some ways come to represent our founding ethos more than the U.S. Constitution itself. The latter is an organizational chart for the governance of a new nation and establishes the underlying legal basis not just for the rights of government, but also for the rights of the people. The Declaration of Independence told the world what we stood for.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed; That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.”

The signers were spot-on with the assertion of a fundamental right to be free. But at the time, they did not in fact deem all people equal, or free, so it was an assertion in word, not practice. Many indigenous peoples had been felled by European diseases or weapons, their lands swept up by European nation-states. Women weren't considered equal citizens. The colonial economy relied heavily on the enslaved labor of kidnapped Africans and their descendants. Over the course of the slavery era — pre- and post-Constitution — millions of Black people lived and died without even a taste of freedom, let alone the ability to pursue their own happiness. And while the shackles started falling off with the adoption of the 13th Amendment, “all men” were not — and still are not in some quarters — viewed as equals. Of the 36 states in existence when Congress moved in January 1865 to end slavery, four states — Delaware, Kentucky, New Jersey and Mississippi — initially rejected the amendment. In fact, Mississippi didn’t officially ratify the end of slavery — by then a symbolic act — until 2013.

So what does that have to do with the death of George Floyd over Memorial Day weekend under the knee of a Minneapolis cop, and the ensuing groundswell of protests around the nation? Everything.

It’s stunning, and a stain on the nation, that racism continues to permeate our society to the extent it does, though with a founding ethos of white supremacy it perhaps should not be surprising. We are, in so many ways, far from the nation we were at the time of our birth, but also chillingly similar. The lie of white supremacy still gets whispered among us, and institutional racism locks into place inequities that the vast majority of America say they abhor, yet allow to live on.

A half-century ago American cities burned in uprisings against oppression, against police departments that served as occupying forces in Black neighborhoods, against unequal access to the promise of America. Protesters demanded to be included under the umbrella recognizing that all people are created equal, that all have an inalienable right to live, to be free, to pursue happiness. Commissions were formed and promises made, but not enough has changed. Yes, laws bar discrimination in the workplace, yet the income imbalance between white Americans and nonwhite Americans persists. Laws also require equal access to education, but our urban school systems are just as segregated now as they were in 1954, when the Supreme Court ordered school segregation to end.

The Declaration of Independence included a bill of particulars indicting the behavior of the British government and the Crown, explaining why the Americans were casting off colonial governance. People of color in this country have their own bill of particulars. It’s not revolutionary; it is a recitation of the nation’s failure to extend to them the full promise of what it is to be an American. Some of that is changing in the wake of the anti-Black racism protests, but this nation has cause to be skeptical that a corner has been turned. Still, we must continue to move forward. For too many people, and for too many generations, the self-evident truth of equality has just been empty words scrawled on parchment. And it is incumbent upon us, as a nation, to turn those words into reality.