Editorial: The U.S. Supreme Court just made it easier for police to pull you over

It has long been too easy for police to stop motorists on the highway — even without sufficient reason to believe that the driver committed a crime. On Monday, the Supreme Court made such stops even easier, ruling 8 to 1 that police may pull over a vehicle because its owner’s driver’s license has been revoked — notwithstanding the fact that it’s common for the driver of a car to be the owner’s spouse, child, neighbor or friend.

The lopsided outcome of the case underscores the fact that liberal and conservative justices have colluded in diluting the 4th Amendment’s prohibition of “unreasonable searches and seizures.” It's an invasion of privacy far beyond the inconvenience of being stopped. Once a car has been stopped, an officer can seize illegal drugs in the passenger compartment if they are in “plain view.”

Monday’s ruling stems from an incident in 2016 in which a sheriff’s deputy in Douglas County, Kan., spotted a pickup truck and decided to run the vehicle’s license plate through a state registration database. The search turned up the information that Charles Glover Jr., the owner, had had his license revoked. The deputy stopped the truck, which Glover was driving. He was charged with being a “habitual violator” of traffic laws.

Glover challenged the stop on the grounds that the deputy lacked "reasonable suspicion" that he had committed a crime — a legal standard looser than the “probable cause” required for a search warrant. The Kansas Supreme Court agreed, holding that the deputy had stopped the truck on a “hunch” that the driver was also the owner (whose license had been revoked).

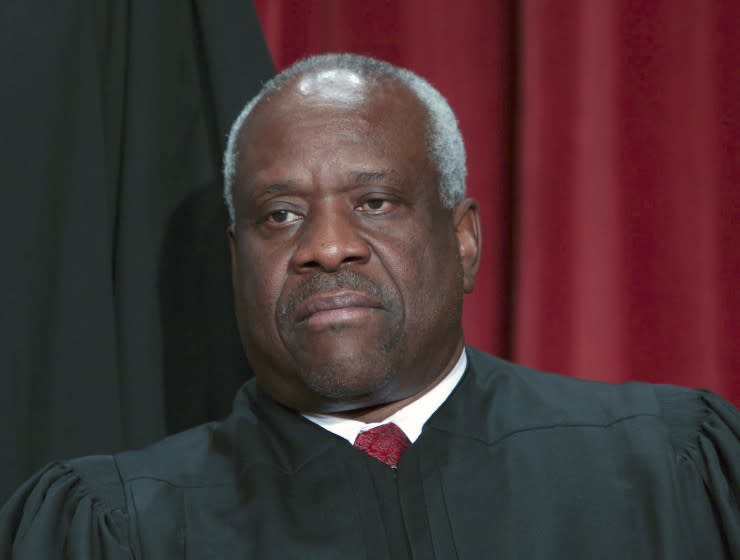

Writing for the majority, Justice Clarence Thomas said that the legal standard of “reasonable suspicion” must be interpreted in light of “common sense.” Besides, he suggested — a point also made by Justice Elena Kagan in a concurring opinion — that things might be different if an officer stopped a vehicle owned by an elderly man knowing that the driver was a young woman.

But as Justice Sonia Sotomayor pointed out in her dissent: “The consequence of the majority’s approach is to absolve officers from any responsibility to investigate the identity of a driver where feasible.” Indeed, it gives police an incentive to be incurious about such details.

Most law enforcement officers are conscientious and respectful of constitutional rights. But too many abuse their power to stop cars — and pedestrians, as with New York City’s infamous “stop and frisk” policy — on the basis of hunches or as part of a fishing expedition. The court has made it easier for them to misbehave.