The communities are side by side. They have wildly different education outcomes – by design.

PHILADELPHIA – Tomea Sippio-Smith still remembers how depressed she felt after participating in an eighth grade math competition decades ago. It wasn’t so much the outcome that bothered her – whether she left victorious was beside the point. Rather, it was the revelation of what was missing from her education.

Sippio-Smith was in honors algebra. She was a smart kid. But upon arriving at the competition, she realized her wealthy rivals had been learning a type of math she’d never even heard of – math Sippio-Smith might never get to learn because it wasn’t offered at her Miami school.

“It was just a poignant moment, seeing what we didn’t have,” said Sippio-Smith, a mother of two. She and her classmates returned to their school with a “sense that it didn’t matter – like, we could try our best, and it wouldn’t matter.” It didn't matter that Sippio-Smith, who was in band, had to play an instrument held together by rubber bands and tape; that she had to learn in classrooms that were falling apart.

Sippio-Smith works largely in Philadelphia but lives in a predominantly white suburb outside the city, so her own children can attend better-funded schools than the one she did. When she moved to the area from Miami, Sippio-Smith, who's Black, sought out housing in Philadelphia proper. She wanted her children to attend its public schools and experience the city's diversity, but she struggled to justify putting them in schools like the ones she attended, where basic services aren't always guaranteed.

“I wanted the culture, I wanted all of that," Sippio-Smith said. "But I just couldn’t make it work.”

The majority of public school assignments are based exclusively on a student’s residential address. Families, in turn, often move in pursuit of the best schools. One in five public school parents chose to live where they do so they could enroll their children in the area’s district, federal data show.

Not everyone can afford to vote with their feet – generally speaking, higher district test scores mean higher home prices. In many cases, according to new research by Bellwether Education Partners provided exclusively to USA TODAY, the resulting segregation is unmistakable. It's part of what Bellwether, a national nonprofit, refers to as "educational gerrymandering": when district boundaries are deliberately drawn – or at least maintained – to keep low-income students out of the most richly resourced school systems.

“Low-income families are effectively priced out of schools that are located in districts that lack affordable housing options," said Jennifer O’Neal Schiess, a partner at Bellwether who co-wrote the report. “And real differences in funding between districts translate into differences in resources for students.”

The geographic lines that separate districts wouldn’t matter if school funding and affordable housing were spread equally across regions. But they’re not. Districts that sit right next to each other often have different levels of both.

Bellwether refers to the boundaries that separate such districts as "barrier borders." Bellwether found nearly 500 barrier borders across the country, and an especially high number in Pennsylvania.

“There may be … rationales for why those (boundary) decisions are made," O’Neal Schiess said. "But ultimately, the effect of those decisions is to sequester revenue and segregate communities based on affordability."

As part of its analysis, Bellwether Education Partners analyzed housing and funding data from districts in the 200 largest metropolitan areas. It assigned each of those roughly 5,700 districts an affordability score.

The score is essentially a relative measure of housing accessibility. What percentage of homes are affordable rentals, and how does that compare with the percentage of families in the region that are living in poverty? (Families with annual incomes below $35,000 are more than twice as likely to rent compared with those who earn more than $75,000.)

The lower a district’s score, the less its affordable housing supply meets the demands of its larger community’s low-income residents. The higher the score, the greater its concentration of affordable housing. When a district with a score below 0.5 sits next to a district with a score greater than 1.5, the boundary that separates the two is considered a barrier border.

Housing affordability is closely tied to school funding largely because of how much money districts can bring in from property taxes – the more expensive the homes, the wealthier the tax base. On average, districts with limited rental housing raise more than double the per-pupil tax revenue compared with districts with concentrated low-income housing.

Across the street, a different reality

Pennsylvania – home to a whopping 500 districts – ranks 45th in the country for the share of school funding that comes from the state. That makes it ripe territory for educational gerrymandering: The less money schools get from their state, the more they have to rely on property taxes.

Pennsylvania’s schools “are overly reliant on local wealth, which results in a lot of disparities," said Deborah Klehr, executive director of the Pennsylvania-based Education Law Center. Pennsylvania spends an average of $4,800 less per student in low-income districts than it does in their wealthier counterparts.

More inequity in education: America headed back to school. Where were the missing kids?

Inequities are especially egregious in the Philadelphia area. There, the juxtapositions between the city – the poorest metropolis in the USA – and many of its most affluent suburbs are jarring.

The Lower Merion School District in a predominantly white suburb 10 minutes outside Philadelphia boasts some of the highest-achieving schools in the state. At least 9 in 10 of its high schoolers perform at or above the level of what’s expected for students their age in math, language arts and biology.

The district is affluent – the median household income is nearly $134,000, according to the Bellwether data, and less than 4% of its students live in poverty. Its affordability score is 0.35 because it has so little affordable housing.

The district brings in more than $32,000 a year per student. Lower Merion High enjoys sprawling green spaces and gleaming buildings filled with all kinds of labs and a glass-encased library. It even has a tiered-seating lecture hall, a black box theater and a natatorium.

Just across City Line Avenue, an education looks a lot different.

Overbrook High, a few miles southeast of Lower Merion High, used to be one of Philadelphia's most in-demand schools. Famous alumni include Will Smith and Wilt Chamberlain.

But as the school's Gothic Revival building deteriorated, enrollment has plummeted. "They used to call this 'the Castle on the Hill,'" a man who was hanging out across the street from the school told USA TODAY. Now, not so much.

Just 1% of the school's students are proficient in algebra, and roughly half of its seniors graduate on time.

Which students missed class during COVID-19? We asked, and schools don’t know.

Philadelphia's poverty rate is twice that of its broader metropolitan area. The Philadelphia City School District's median household income is roughly $46,000, according to Bellwether data, and 32% of its students – nearly 9 in 10 of whom are children of color – live in poverty. The district's affordability score is 2.16 – 1.81 points higher than Lower Merion's.

Even though the city district taxes its residents at a higher rate than most of its surrounding suburbs, it generates less revenue for its schools because it has little wealth from which to draw. The district brings in less than $21,000 a year per student – two-thirds what Lower Merion brings in. The region is filled with such juxtapositions, including between certain suburbs (see, for example: Haverford and Upper Darby).

The Education Law Center, in partnership with the Public Interest Law Center and the firm O'Melveny, contends the state's school funding system is unconstitutional and sued the state. The case heads to trial next month.

For more than two decades, a Pennsylvania school district’s funding depended almost exclusively on how much money it received from the state in 1991. No matter if the district’s population was growing or it served a large population of English-language learners or lots of children living in poverty.

In 2016, the state adopted what’s known as a weighted student funding formula, the basic idea being that high-needs districts should get extra money. But the formula applies only to money added to the state’s education budget after the 2016 law was introduced – just 14% of Pennsylvania’s basic education funding this year. Funding continues to be woefully inadequate and unequal, according to the lawsuit, filed seven years ago.

POWER Interfaith, a coalition of Pennsylvania congregations, launched an education campaign a few years ago aimed at rectifying inequities, in Philadelphia and beyond. The campaign revolves around a simple premise: A child shouldn’t have to live in a white, wealthy area to get a good education.

The group has led marches between low- and high-income districts. The Rev. Eric Goode, who helped lead a march this year between Philadelphia’s Overbrook High and Lower Merion High, is a product of the city’s public schools. He remembers how hard it was to thrive. He knows how hard it can be to this day.

As Goode approached Lower Merion’s campus alongside fellow activists this summer, he felt like he was in a different universe. Just a few miles across City Line Avenue, the school exuded exclusivity – marchers couldn't even access the grounds, he said, because they were closed off.

'We’ve chosen to stay because we shouldn’t have to leave'

Autumn Smith, Sippio-Smith's daughter, appreciates all the opportunities she's had since moving to the Philadelphia area from Miami and enrolling in a suburban district. She's part of several clubs. She plays sports and has done theater. Most of her classes are honors or advanced placement courses.

She's struggled academically, but she's thrived as a result. "If you don't know how far you can go, then you'll never push yourself to do more challenging things," said Smith, in 11th grade.

Sippio-Smith moved Autumn and her son to the suburbs precisely so they could have those opportunities.

She wanted Autumn, who has an auditory processing disorder, to get the speech therapy she needed. She wanted her son, who’d been in the gifted class back in Miami, to be in an accelerated program. Those supports “help to create an environment that is symbolic of a dream," said Sippio-Smith, who got her master's in education policy at the University of Pennsylvania and works with the nonprofit Children First.

She sought to enroll her children into a few Philadelphia schools where, based on her research, they had a shot at realizing their dreams. But she either couldn't get her kids in – many of the city's most sought-out public schools have selective admissions – or couldn't afford to live in the neighborhood that fed into them.

We all have a unique perspective: Sign up for This is America, a weekly take on the news from reporters from a range of backgrounds and experiences.

Boundaries for individual schools, such as the elementary or middle school that serves a neighborhood, are another form of educational gerrymandering, a report by the Urban Institute suggests. Analyzing every metropolitan area in the USA, the policy think tank found more than 2,000 pairs of neighboring schools – largely within the same district – that are “vastly unequal” in terms of factors such as race, program offerings and test scores. Fifty-eight of those boundaries are in the metropolitan area that includes Philadelphia.

One such boundary is between Philadelphia’s Penn Alexander and Benjamin B. Comegys schools, both of which are public and serve students in grades kindergarten through eight. Penn Alexander is one of the city’s best-performing public schools – it benefits from a public-private partnership with the University of Pennsylvania – and kindergartners are admitted through a lottery. Most of its students are white or Asian. At Comegys, just 5% of students are considered proficient or advanced in math. Most of its children are Black.

Though the two schools are separated by little more than a mile, the boundary that runs between them means many families of color are excluded from Penn Alexander.

Maritza Guridy is a mother of six, four of whom are in Philadelphia schools, and she's long contended with educational gerrymandering. She wishes her kids could experience the kind of education people in wealthier city neighborhoods and the suburbs enjoy. But she refuses to move.

“We won’t leave our community because we’d rather be an example,” she said. “It’s easy for someone to say, ‘Well, I got my degree, I got my nice job. I’m moving out to the suburbs.’ We’ve chosen to stay because we shouldn’t have to leave.”

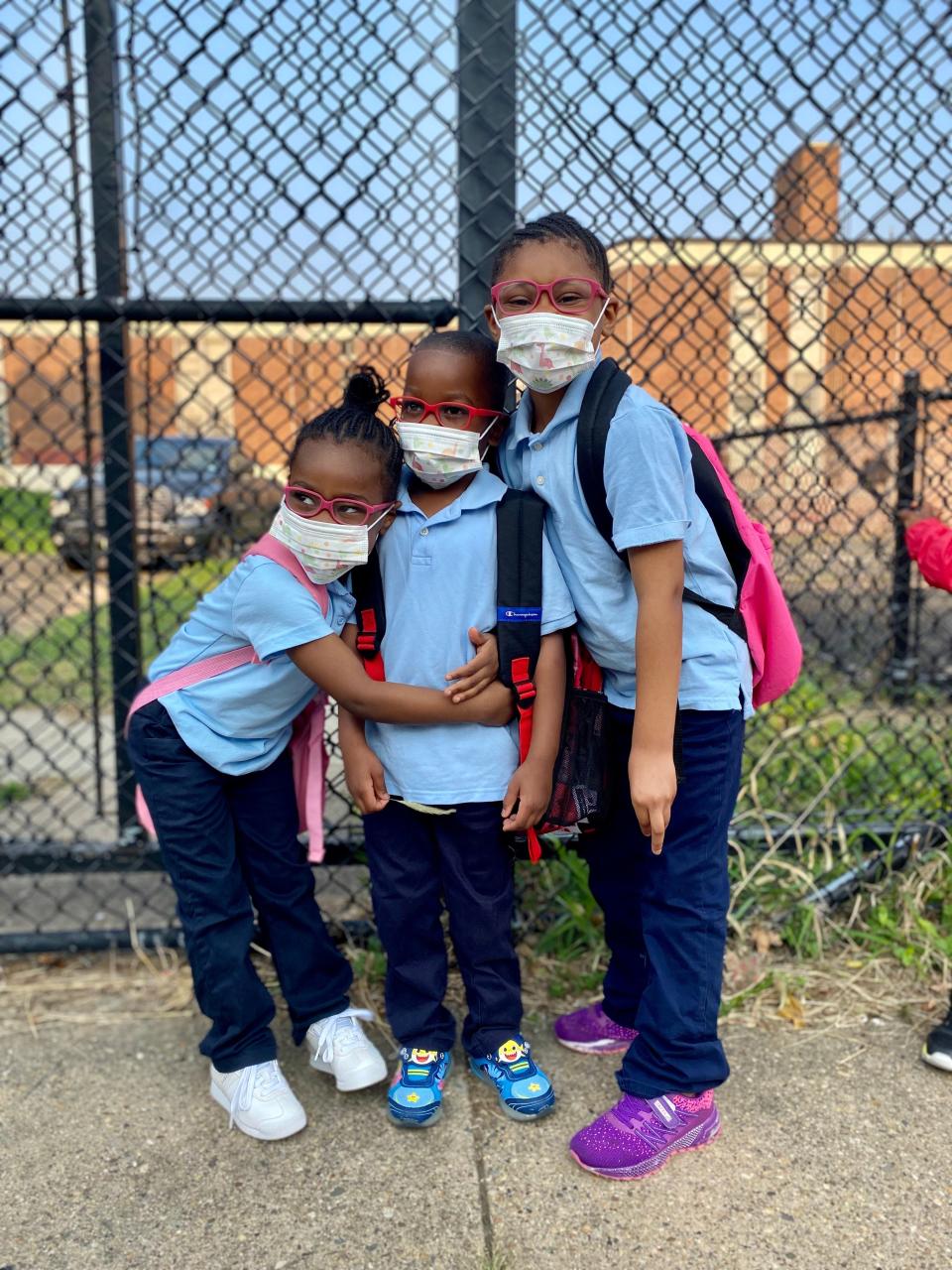

Guridy didn’t have many options when it came to choosing a school for her three youngest, whom she either adopted or is fostering. The elementary school that serves her street? Too dangerous and run-down. Private school? Too expensive. The Afrocentric charter school her 16-year-old daughter attended and enjoyed? Too far and, like the elementary school, too dangerous – it’s in Kensington, a center of the opioid crisis that has been described as “the Walmart of heroin.”

Guridy settled on a relatively close public school that leaves a lot to be desired but is making strides with what's allotted. The concrete building sits across the street from a beer and cigarette store and, like many Philadelphia campuses, is contaminated with asbestos – but at least it’s making improvements. Thanks to millions of dollars in investment, it upgraded its technology and HVAC system and began an asbestos-removal campaign. It planted trees to improve air quality and a garden that grows tomatoes and collard greens.

Guridy, who's Dominican, said those investments have trickled in largely because the neighborhood is gentrifying. Philadelphia has in the past decade or so experienced a sort of reverse white flight. The gentrification has brought more money to some of the city’s public schools, thanks in part to private fundraising and noisemaking by middle-class parents.

“It gives you a melancholy feeling,” she said. “Like, you’re happy it’s happening, but you wished it happened sooner. You wish that all these opportunities that are now happening would have been afforded to the other children who used to come to this school.”

At their best, real estate markets and public school systems enjoy a symbiotic relationship. An area’s real estate improves the quality of its schools, and the schools’ quality improves demand for the surrounding real estate.

Home prices in Pennsylvania districts boasting high student test scores increased at a greater rate than in districts where children underperform, according to a report in 2017 by the Reinvestment Fund, a community development financial institution. If a district sees a mere 1% growth in student achievement, the report concluded, its average home prices could increase by as much as $620. The small hikes in home values make a big difference when spread across a community, adding hundreds of thousands of dollars to a town’s coffers

At their worst, real estate and schools detract value from each other until there's little left. “The success of schools and students makes communities desirable places to live, and when schools struggle, communities struggle to retain families who can afford to move,” the report reads.

Two dozen Philadelphia schools were shut down permanently starting in 2012 largely because of enrollment challenges and safety hazards. Their abandoned buildings are, advocates said, a reminder of how education and housing policies can trap certain people in a vicious circle of poverty.

How to fix it

Barrier borders – and the educational gentrification they produce – are a human-made problem that can be addressed through policy reforms, the Bellwether report suggests.

States could contribute a larger share of education funding to mitigate the impact of property tax differences, for example. Places that have done so have seen large improvements in kids' educational attainment and in the likelihood that students will experience poverty in adulthood.

Pennsylvania's Republican-controlled Legislature increased funding to all the state's school districts, including additional money to the poorest ones through an initiative known as Level Up. "Pennsylvania has been a national leader in working to address this dilemma," said Mike Straub, a spokesperson for Pennsylvania House Speaker Bryan Cutler.

Still, the inequities persist. "Pennsylvania has one of the most unfair school funding systems in the country, and it's hurting students and property taxpayers," Kendall Alexander, a spokesperson for the state's Department of Education, said in an email. "That's causing too many urban and rural districts to fall behind, especially lower-income communities that are forced to raise property taxes."

Pennsylvania's Gov. Tom Wolf, a Democrat, proposed the weighted funding formula apply to all basic education spending. But money is just part of the problem: Housing should be spread across locales, and enrollment should be expanded to welcome families who live outside wealthier districts, the Bellwether report suggests.

Quibila Divine, a longtime education advocate in Philadelphia, is hopeful about the reforms the lawsuit could bring, but it’s a bittersweet optimism. Philadelphia schools have always been underfunded, as have districts across the state that serve lots of poor children of color. Not until reverse white flight did people want to do something about the problem, Divine suggested.

Divine and her sister, Sylvia Simms, were bused to predominantly white schools on the other side of town, and they appreciate the opportunities they had as a result.

On a drive traversing Northern Philadelphia's neighborhoods, Simms pointed out examples of gentrification – the white people on bikes, the coffee shops, the shiny, modern apartment complexes.

Asked whether, if they had school-age children and could afford moving, they’d send their kids to a district like Lower Merion, neither Divine nor Simms hesitated. Yes, of course, the sisters said, because they’d have more opportunity. Simms’ granddaughter moved to Delaware to stay with her grandfather just so she could attend its schools.

That's a choice families should never have to face, they said. Philadelphia’s residents – any poor area's residents – shouldn’t be forced to settle for their school district. And they shouldn’t be forced to leave, either.

Contact Alia Wong at (202) 507-2256 or awong@usatoday.com. Follow her on Twitter at @aliaemily.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Education inequity in America isn’t an accident. It’s by design.