Educator whose leadership made KC’s West Side library ‘a lifeline,’ dies at 102

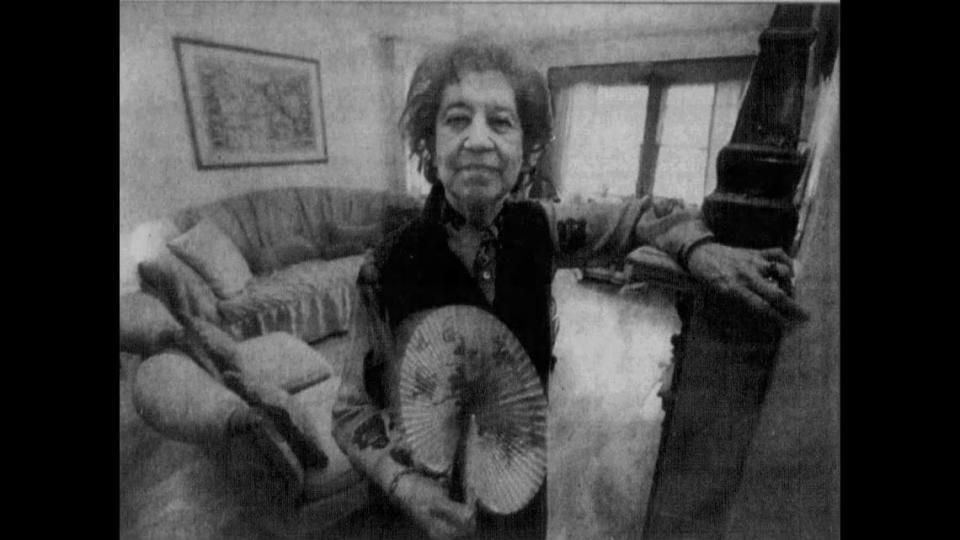

A watercolor painting of an elegant woman with a bright smile looks out over visitors to the library in Kansas City’s West Side neighborhood.

The namesake of the Irene H. Ruiz Biblioteca de las America was well into retirement at the time the portrait was made nearly two decades ago to commemorate this pillar in the city’s Hispanic community.

Ruiz, who is lauded for her long devotion to education, immigrants and children, died Sept. 3. She was 102.

Those who knew her recall the legacy she left behind — including a vast collection of Spanish literature and resources at the library and one of the first known oral histories of Mexican immigrants to Kansas City.

Oral histories and literary expansion

Ruiz was born in Texas, one of eight daughters of a Mexican immigrant father and a Texan mother, said her son, Bret Ruiz, 65, who works as an academic advisor at DePaul University in Chicago. He is one of her three sons.

Encouraged by her parents to go to college, Irene Ruiz got a teaching license; but her first employer was the U.S. government. During World War II, Ruiz, who spoke Spanish, English and Portuguese, was hired as a spy to listen in on calls of famous movie stars who the government suspected of being communist sympathizers, her son said.

In the 1960s, Ruiz and her husband, Francisco Ruiz, moved to Kansas City where he took a job as a language consultant and she took a job as an educator, both with the Kansas City school district, Bret Ruiz said. Francisco Ruiz later died in 1993 at the age of 64.

Ruiz eventually left her job as an educator with Kansas City’s public schools to pursue a degree in library sciences and work for the Kansas City Public Library. In the 1970s, she was placed at the West Branch where she noted an abundance of books on Ireland. But she couldn’t find a single book in Spanish, despite the neighborhood’s abundance of Spanish-speaking residents.

She began collecting books, newspapers, magazines and movies, all in Spanish. Few materials were printed in Spanish in the U.S. at the time, said Julie Robinson, who serves as the library’s Refugee & Immigrant Services & Empowerment Outreach Manager. So Ruiz shipped them in from Spain and Latin America.

She even shipped in Spanish comic books in the hopes of encouraging more kids to read. The concept of stacking classic literature beside comics was so unheard of at the time that a newspaper in Ireland wrote about it, according to a Star article from 2001.

Bret Ruiz described his mother as strong, elegant and down to earth. It made sense that Irene Ruiz, who volunteered to translate for indigent and undocumented people at the local courthouse, wanted to transform the library into a quasi-community center.

“It wasn’t just about the books. It was about bringing people together, respecting them,” Bret Ruiz said.

His mother had a vision.

“During her two decades as director of West Branch, Irene Ruiz transformed a storefront library into a depository of Latin American literature, bilingual materials and taped interviews that she conducted,” Joel Balam de Escalante wrote in The Star at the turn of the century a few decades later..

Ruiz had turned the library into a repository not only for books, but also for language resources. She began helping Kansas Citians who could not speak English learn the new language, and fill out important documents like job applications.

In the late 1970s, she began gathering the oral histories of more than 70 members of the Hispanic community, documenting the stories of immigrants and first-generation Kansas Citians. The project, then called “the Mexican-American archives project,” was recently digitalized.

Among those she interviewed: chefs, the Director of the Guadalupe Center, a police officer, teachers, artists, homemakers, the principal of Douglas Elementary School, parish staff members and politicians, including Paul Rojas, who just a few years earlier became the first Latino elected to Missouri’s General Assembly.

“She helped plant the seeds for educational growth among our people,” said Rojas, now 89, who was born on the West Side and proudly owns a home just two blocks from the Ruiz library.

A fight to keep the library in the West Side

While Ruiz was still a librarian, the West Branch was a 1,000-square-feet building on Southwest Boulevard. Thanks in part to Ruiz’s efforts to grow the library’s influence, they quickly outgrew the space.

At the same time, the library’s board was discussing shutting down both the West and Westport branches in favor of opening a consolidated branch somewhere in between.

Few people were happy with the decision. Ruiz was among a handful of community members who went door to door, asking neighbors to fight to keep the library branch in the heart of the West Side, said Jorge Coromac, Director of the Westside CAN Center. She knew many people in that area were without cars. The branch needed to be within walking distance of those who used it, Ruiz insisted.

The library board finally agreed to build a new branch, but to do so on the West Side.

Content with the knowledge that her beloved library collection would not be moved out of the neighborhood she cared so deeply for, Ruiz retired in 1996. She was in her mid-70s. But she didn’t disappear from the library. The matriarch still made regular appearances to read to children in her free time.

Then came the next battle: What to name the new building.

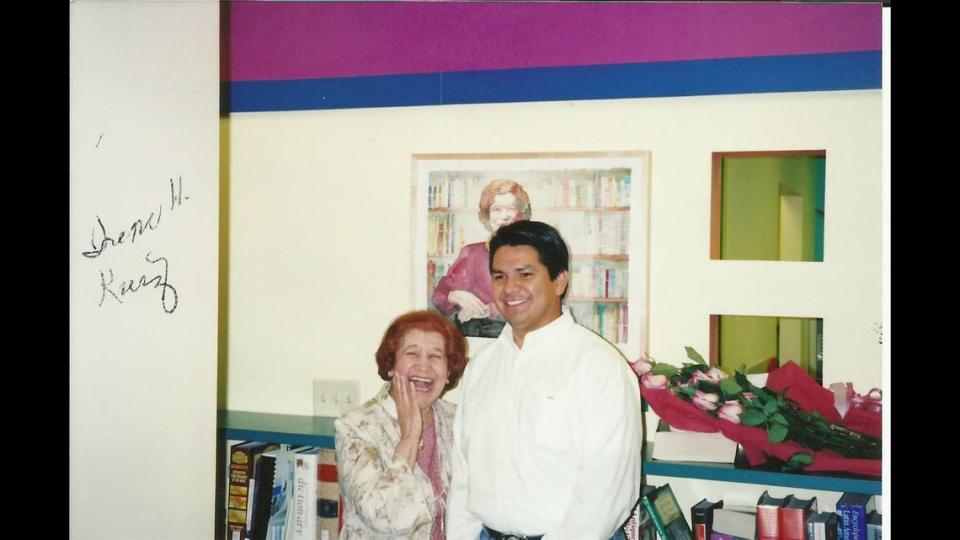

A June 2001 article in The Star detailed the Westside community’s year-long push to name the new branch after their beloved, retired librarian.

The library board initially pushed back, hesitant to name a building after a former employee, especially someone who was still alive. But the West Side community insisted. The library board sealed the deal in late June.

The grand opening of a newly constructed branch at 2017 West Pennway was scheduled for Sept. 11, 2001, but the terrorist attacks halted everything, said Robinson, who had taken over as branch lead at the time. The library quietly opened a few days later.

The library was officially dedicated in 2006, the same year Ruiz was named the annual “real life hero” at Primitivo Garcia Elementary School, joining the ranks of Cesar Chavez, Buck O’Neil and Primitivo “Tivo” Garcia.

“For many patrons who were trying to learn English or become citizens, the library was a lifeline,” The Star wrote in an article commemorating the day.

‘A trend-setter’

Ruiz was so well-respected at Primitivo Garcia Elementary School that when students misbehaved, the vice principal used to threaten to bring in Ruiz to talk to them about their behavior, Robinson said. They usually straightened right up, afraid to disappoint Ruiz.

“Every kid that saw her wanted to talk to her and tell her what was going on in their life. And that’s an incredible thing, when you have a 10-year-old talking to a woman who was in her 90s by then,” Robinson said. “That, too, is a legacy, that she stopped to listen to them.”

Robinson called Ruiz, who never had a drivers’ license, but did have a college degree, a “trend-setter” and a “pioneer.”

“If you look at her life and the things that she did in times where women got married, stayed home and raised children. They didn’t go to work. She was a working mother.”

Ezekiel A. Amador III, 54, a neighborhood volunteer and advisory committee member for the Tony Aguirre Community Center on the West Side, said Ruiz laid the groundwork for the flourishing network of community resources that exists today.

The Ruiz branch houses a free seed library, passport services, youth programming and features chess tables out front, something he said likely would’ve been approved by Ruiz, who was always concerned about finding ways to help and bring activities to “the muchachos on the Boulevard,” some of whom were undocumented.

“She’s part of that generation that showed how we should be,” Amador said.

Now, he and many other leaders and volunteers on the West Side continue her legacy, including by hosting the annual back to school events and fall festivals in partnership with the library branch and the Westside CAN Center to serve the neighborhood’s youth.

“It is beautiful that we can see the amazing influence of Mrs. Irene back in those days thinking up a better community by having access to literature for people to read and learn,” said Coromac, with the CAN center.

The Ruiz branch remains one of the only bilingual libraries in the metro, he said.

Bret Ruiz said the watercolor of Ruiz, which now hangs in requiem, captures his mother’s ease and grace.

He said in Spanish, the word respect is hugely important. His parents loved their community, and in turn they were respected.

“Thirty or 40 years ago, whether you lived in this area or that area, Latino voices were not being heard,” Bret Ruiz said. “And so my parents said, ‘We want a place at the table, and we’re also going to speak for people who can’t speak.’”

They tried to bring a lot of light, and really let the West Side and the people there shine.”