These educators want to change K-12 grading. How a search for fairness echoes in Delaware

One grade book filled the projection screen, then another.

Bobbing heads of teachers, counselors and Appoquinimink administrators absorbed pen strokes, packed margins, and names stacked beside points. Two more followed. One brimmed with assignments, the next nothing like it.

“There were so many confused faces,” Nick Hoover said, recalling a 2022 grading workshop. “They’re like, ‘Why is that?’ And ‘Why is that?’ But ‘Why is that?’ Nobody knows. We showed four different grade books, and they were all very different.”

Attendees were left puzzled as each flashed across the screen.

“By the way,” the educator continued, “nobody really understands anything about grading.”

His Delaware district is just one hoping to reimagine it.

A change in grading protocols is gaining momentum across the country as education reels from pandemic impact, a digital divide laid bare and renewed focus on racial equity in the United States. In it, teachers and administrators are challenging the equity in the letters A-F and practices that have followed instruction for generations.

To them, there must be a fairer way. And the search begins to find it.

Grading styles and function vary from classroom to classroom, system to system. Typically children are penalized for late or incomplete work, with homework and quizzes stacking up throughout a marking period. Sometimes, rewards come for good behavior like class participation or in chances for extra credit.

These structures tend to give advantage to one type of student. Studies show it’s the child with a supportive family, higher income and peace at home. It’s not the student who finds internet only at school or a local library, not the teen looking after siblings, not the young English learner who can’t ask a parent to help with homework.

Joe Feldman couldn’t shake it. Traditional grading bothered him from teaching high school English to filling an office in New York City. By 2018, the education researcher published his book on “Grading for Equity."

“Traditional practices actually perpetuate disparities that have been going on for years by race, income, education, background, language,” Feldman said. “And it's time for us to give teachers access to the more contemporary research."

DSU:Colleges are shrinking. But HBCUs like Delaware State are riding a wave of their own

In Northern Virginia, Arlington Public Schools is testing equitable grading elements — treating homework like ungraded practice, doing away with extra credit, veering away from 0-100 — leading toward possible policy overhaul. Santa Fe Public Schools has begun moving to standards-based grading, or a 1 to 4 scale based on content alone in New Mexico. Some schools across California, Maryland and New England already host similar measures.

Proponents say they aim to filter out everything but academics, letting students find motivation in their learning. Opponents aren't so sure motivation will be easy without familiar letter grades.

But in a time of alarm in education, from feared learning loss to whistles of grade inflation, there doesn’t seem to be one clear answer.

“It's everywhere. There's a real tension between teachers, between school board members. If you really go to a purely standards-based grading program ... there are real trade-offs to doing that, too,” said Seth Gershenson, associate professor at American University, whose research links student achievement with high expectations from teachers.

“So there's a very salient tension in the air right now.”

How does any of this even work?

Ashley Zeroka's bright second-grade classroom, near the center of Middletown’s Lorewood Grove Elementary, is no stranger to grading without letters. Kindergarten through second grade already used 1-4.

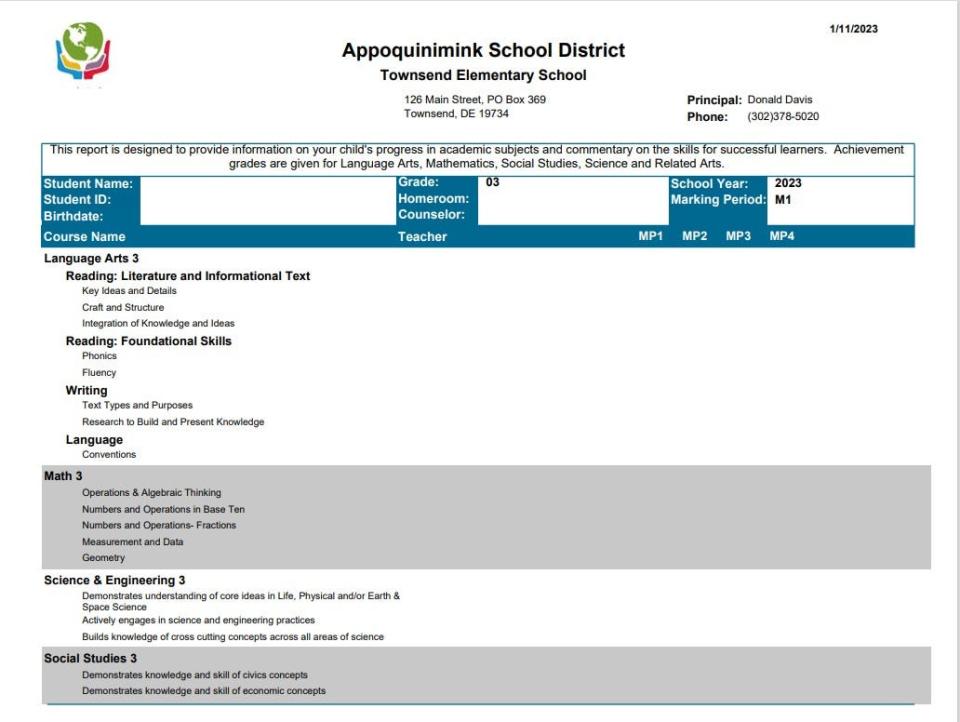

But this fall, Appoquinimink Public Schools expanded that scale across all of elementary. For the first time, third through fifth grades would also be graded on a standards-based, 1-4 scale. And they did it for a reason.

“I think you'll see a shift,” Zeroka said, having just wrapped up the year's first parent-teacher conferences. “Mind-blowing when you hear about it at first, but I think once the work gets settled, more people will see the value of it.”

Core subjects — say math, science, reading — are broken into a set of expectations, each earning a level of mastery from 1 to 4. Multiple, specific standards come together under each subject. Mastery of the subjects fluctuates as learning continues, taking only the end-level of understanding to report cards.

Behavior — say working well with partners, raising hands in class, showing up late — are removed from academic cores. Instead, that feedback fills a different section.

“So that's a shift,” said Gina Robinson, assistant superintendent of elementary. “Typically, we like to give grades based on what type of student they are. And that's where the equity comes in: We want to make sure that we're really addressing the academics.”

Homework is solely practice, Robinson continued, minimal and always based on covered material. Extra credit, like getting that syllabus signed, attending an exhibit, are all but irrelevant.

“We're going to be able to provide parents with more specific information about their student and their student's learning than we've ever been able to before,” she said. “When you look at a traditional grading system, you get an A, what does that a really mean?”

It could mean something a little different in every U.S. classroom.

“Grading for equity” claims to make targets concise and unmoving. Some schools have taken bits and pieces of Feldman's basic concepts — accuracy, bias-resistance, motivation — and implemented them in steps.

Appoquinimink elementary schools took years to settle on a plan. And, while Robinson said they’ve only scratched the surface, that hasn't come without its opponents.

Impact:Delaware Online stories, your stories, that made a difference in 2022

“Change is really hard," Robinson said. "And you can show people all the research, you can explain all the reasons why this is a more equitable practice, but until people dig in, you’re going to have resistance.”

Stacey Drechsler just wants her youngest to be ready for what's next.

A daughter in third grade, a son in fourth, they both look up to the oldest sibling studying engineering at the University of Delaware. Only, their grades at Silver Lake Elementary look a bit different.

“At this point, I can't say whether it's going to be good or bad," Drechsler said. "But I can compare it to what my older son had, and I don't think they try as hard with 1-4 as they did for the letter grades.”

Parent-teacher conferences didn't feel too different, she said, and her fourth-grader doesn't seem to pay any mind to the changes. But the Middletown mom remembers using cash to reward great grades. She remembers helping her Appoquinimink High School grad apply to colleges, believing his transcript spoke volumes.

“He had to earn his higher grades,” she said, recalling his choice between Delaware and Penn State. “And I would be concerned, you know, having kids that are going to be graded differently.”

She may be right to expect a tougher battle upriver.

Wait, what about high school?

Projector off, his grade book workshop was just a starting point.

Nick Hoover, director of Secondary Curriculum, Instruction and Assessment with Appoquinimink, is watching elementary teams closely. He wants to bring elements of equity to middle and high school levels, too.

Today his system is halfway through a four-year plan to revamp policies. A final product has yet to form.

“The end result, I'll say, is going to be a portfolio-based grading and assessment system,” Hoover said. A workgroup has been testing strategies for a long-term plan while outlining standards for about two years.

“Separate out behaviors. Eliminate the 100-point scale. Eliminate averaging," said the administrator and former social studies teacher. "If those are our big goals, then how do we do that?”

As it stands, those answers aren’t settled.

School outside?As outdoor preschools gain traction after COVID-19 pandemic, states work to unlock funding

Middle and high school teachers will likely assess general skills, classroom behaviors and core academic standards related to each course, all separately. Each student's core portfolio would likely focus on “summative” assessments, like tests or essays, over “formative” items like homework or an early pop quiz.

The structure would aim to stop punishing students for learning as they go.

“The first thing people think of is like, ‘That's it! We're not gonna have any grades. And it's just this fluffy type of thing,’” Hoover said of potential protocol. “It's like, no, no, no. That is not what that means.”

Standards would be listed clearly, he said, a rubric outlining benchmarks for a particular grade level, in a particular subject. The rubric may carry a similar 1 to 4 scale.

“We haven't finalized that,” he said. “Eventually, we will still have a report card, we still have a GPA for high schools." But, Hoover would like to see standards go directly into a GPA, removing "the middleman" of letter grades.

“Can the system handle that?" he posed. "I don't know.”

There are two years left to figure it out.

A real world of expectations

People have worried about grade inflation — marks reflecting higher achievement than actual content understanding — for decades, said Seth Gershenson, the American University professor and researcher. Pandemic disruptions just revived the concern.

More assignments became pass-fail. More standardized tests were eliminated. More pressure mounted on entrance exams like the LSAT and GRE. Many colleges already filtered weighted grades and other elements in assessing applications.

The University of Delaware has gotten used to digging deeper.

“Determining homeschool transcripts, international transcripts, all different grading scales — that piece isn't new,” said Douglas Zander, executive director of admissions in Newark.

Most of the roughly 40,000 applicants each year do come with grades easily entered on application software, he said, but there have always been exceptions. That includes standards-based scales.

Nation:More schools are opting for four-day weeks. Here's what you need to know

More:University of Delaware is growing. Here's what President Dennis Assanis says about what's next.

“It just means that we're going to have to pull those and give them to a special reader who's been trained in that, which isn't the end of the world,” Zander said. “Currently, they're fairly rare.”

Admissions specialists already communicate with secondary schools across the small state, he said, so any grading change probably wouldn’t come by surprise. Outside of Delaware, though, Zander understands reservations.

“It really depends on the resources at the institution,” he said. Does it have the personnel to slow down the process? Do lofty application loads make slowing down unappealing? Anything that makes one application less attractive to the system understandably gives pause.

"I wish that weren't true," he continued. "But I think it is."

Regardless, the executive with over 40 years in education said institutions must continue challenging typical pipelines to higher education.

And advocates for equitable grading hope they've found one way to get closer.

How We Live reporter Sammy Gibbons contributed to this report.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY NETWORK: Do we need a fairer way to grade? Some Delaware teachers think so