Efforts in Arizona to rescue migrants and identify remains are model for other states

ORGAN PIPE CACTUS NATIONAL MONUMENT — Tom Wingo exited the charcoal-colored SUV and approached a group of about 35 mostly men and a few women who had slipped through a hole in the 30-foot border fence separating Arizona from Sonora, Mexico.

“Welcome to America,” he told the group, eliciting smiles as they began to chat excitedly and tried to figure out who he was.

Wingo has volunteered with Human Borders for nearly eight years. He normally wears khaki pants, a red long sleeve shirt and a cowboy hat. The red shirt matches the red sign on the side of the SUV with a white cross and the words “Samaritanos sin Fronteras,” Samaritans Without Borders.

After crossing the fence, the group sought U.S. Border Patrol agents to turn themselves in for asylum processing. But Tom knew it would take some time for them to arrive because border agents along this stretch of the border are stretched thin.

The group had traveled to the U.S.-Mexico border from India. They spoke limited English but managed to convey that some in the group had been traveling for nearly six weeks, flying to Europe before making their way to northern Mexico.

Wingo directed them to one of six new water stations that Humane Borders installed along the border fence in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Since the summer, this park became one of the busiest areas along the entire southern U.S. border, with agents picking up hundreds of migrants each day.

“In 2 minutes they (smugglers) can cut the wall, people come through and then they take off. And then Border Patrol finds the people, finds the hole, and then calls the welders, and so it’s a constant circle,” Wingo said.

A few hundred yards away from the water station where the group of migrants from India waited, farther down along Puerto Blanco Drive, a dirt road that rings the rugged desert landscape of the national monument, U.S. Border Patrol agents set up a station over the summer.

Large brown military tents poked out from the towering saguaros that provide shade for migrants picked up by agents and waiting to be transported.

Every day on Arizona State Route 85, dozens of white vans carried up to 15 people, and large white buses with the capacity for 50 more, take migrants from Organ Pipe to the Ajo Border Patrol Station for processing.

In 2023, Border Patrol agents encountered more than 617,000 migrants at the Arizona border. The Sonoran Desert once again became the busiest corridor for migrant crossings along the entire U.S.-Mexico border. The volume was so high there were not enough agents and buses to process them. It would take hours to pick up a single group.

In his experience doing runs several times a week, Wingo said, the migrants crossing at Organ Pipe wait to be picked up by border agents at the water stations next to the fence. But he worries for the migrants who evade border agents and instead trek into the arid, rugged desert.

Even though the number of migrants crossing has gone up, there has not been a corresponding increase in the number of migrant deaths.

In the last fiscal year, which ended in September, the remains of 180 migrants were recovered along the Sonoran Desert, the sixth highest number on record in southern Arizona, according to the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner.

The year was especially hot and dangerous with record-breaking temperatures in most of Arizona. Organ Pipe National Monument recorded 14 days of temperatures above 110 degrees Fahrenheit during the three hottest months of the year, July through September, according to data from the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration.

Each year, the U.S. Border Patrol’s Tucson Sector, which covers the eastern two-thirds of the Arizona border, surges staff and resources to the area near Organ Pipe and the surrounding desert during the summer months when the number of rescue calls spikes.

This past year, the Tucson Sector saw a massive spike in rescue calls from people lost, stranded or injured along the desert. Agents recorded 28,000 rescues this past year, according to Justin de la Torre, the deputy patrol chief.

“Border Patrol, more often than not, has the best chance of reaching those people and saving their lives, more so than some of the state and local rescue assets that are out there,” he said.

However, as the number of migrant deaths increases in other parts of the U.S.-Mexico border, southern Arizona is and remains a focal point and a testing ground for best practices for how to search for and rescue migrants, as well as to recover and identify their remains.

The state’s extensive experience over the past two decades has led to a centralized system for collecting information, as well as the ongoing collaboration and cooperation between local and federal governments on the ground and an extensive network of civil nonprofits, even when their efforts occasionally come into conflict.

“It just got cobbled together over time. There was no ah-ha moment. It's just time and volume,” said Gregory Hess, the medical examiner for Pima County, the repository for information and bodies recovered at the border.

Farther south: In southern Mexico, the cost for migrants to reach the US is increasingly death

Here's how Arizona searches for and rescues migrants

After a baseline year during the COVID-19 pandemic, border crossings are on a rapid rise each year along the southern U.S. border. And not just on the rise. Migrant encounters have reached record levels, reaching more than 2.4 million last year.

Arizona’s Sonoran Desert reclaimed its status as the nation’s busiest crossing area. It was a distinction it kept for the better part of the past 25 years until migration flows shifted east to Texas' Rio Grande Valley starting in 2013 and then to Del Rio over the past three years.

In 1994, the U.S. Border Patrol began to implement a “prevention through deterrence” policy. It fortified the border along urban areas, believing this would deter migrants from crossing through more remote and risky areas.

But at the turn of the century, as more migrants began to cross through Arizona, more also died or went missing attempting to cross through rugged, parched desert terrain.

As migration flows shifted east a decade ago, the number of migrant deaths along the Sonoran Desert dropped for some time. But during the pandemic the numbers rose again, peaking to a record 225 remains found in 2021, the deadliest year on record in Arizona.

The peak corresponds with heavy restrictions along the U.S.-Mexico border when asylum processing was shut down at ports of entry and border agents expelled migrants back to Mexico immediately after encountering them under the public health rule known as Title 42.

The data on the number of remains recovered each year is available because the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner tracks the recovery of what it calls "undocumented border crossers."

Their work extends to neighboring Santa Cruz and Cochise counties. That covers the eastern two-thirds of Arizona’s border with Mexico. Since 2000, the office has recorded the recovery of 3,700 migrant remains.

As the main forensic office along the border, the medical examiner in Pima County takes in the remains of migrants found by law enforcement agencies such as the Border Patrol and the sheriff’s offices, as well as searches conducted by humanitarian nonprofits combing through the desert borderlands.

“You have to have a conscious effort to be able to track it. That's step one,” Hess said. “If you can't do it, then, you know, you can't report any information about it. And then if you haven't a mechanism by which you could report information about the deaths that you receive, then you have to be willing to do it, right, or make it available for people to see.”

The medical examiner collaborates with the Tucson-based nonprofit Humane Borders to create a Map of Migrant Mortality, which uses geographic information systems to track the areas along the Sonoran desert where migrant remains are found.

The interactive map allows users to search by year, location and other markers. Results include detailed information such as the date when the remains were found, and if known, the cause of death, name and age.

Humane Borders operates 35 water tanks along the Sonoran Desert. The blue tanks are marked by 30-foot blue flags. In 2022, the group put out nearly 20,000 gallons of water. Last year, that number was much higher because of six new tanks in the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument.

Laurie Cantillo, a board member with the group, said the data points, along with searches in the desert, allows them to track where people are crossing. That information helps them decide where they should install the 55-gallon water tanks.

But it also serves another purpose.

“That way Border Patrol, humanitarian groups, everyone understands the magnitude of the problem. And keep in mind that what you see on the death map is only the data that we have, the remains that have been found," Cantillo said. "How many more are out there that haven't been found?"

The Border Patrol also actively tracks migrant routes and locations where their agents rescued migrants or recovered remains.

The agency uses that data to map out where it puts 182 rescue beacons along the border. Thirty-four are in the Tucson Sector. The beacons are about 35 feet tall and have strobe lights. The beacon allows migrants to call for medical help and provide coordinates for rescuers.

The sector ended the fiscal year with more than 373,000 encounters, a nearly 50% increase over the previous year. It resulted in more than 12,000 emergency calls from migrants in distress.

“It's a tough thing to do. But at the end of the day, when there is a life or safety-type situation, that becomes the priority. And I can tell you that this past summer, the majority of the work that we were doing was rescuing people day in and day out, nonstop rescues,” de la Torre said.

Technology has made it easier for migrants to call for help. Cellphone coverage has greatly expanded even in more remote parts of the border. And more migrants now carry cellphones that allow them to call 911. The calls are answered by the sheriff’s office emergency dispatch and routed to the Border Patrol.

Historically, many of those emergency calls originated from the Center for Information and Assistance for Mexicans at the Consulate of Mexico in Tucson, a call center staffed by about 50 employees.

It began in 2013 when the area that the Consulate in Tucson covered received the greatest requests for assistance along Mexico’s consular network in the United States. Families would call to report a missing loved one. They shared that information with the Border Patrol.

“Many people, especially Mexicans who traditionally have had little success claiming asylum, don’t want to be found by Border Patrol,” said Rafael Barceló Durazo, the consul general in Tucson.

“In reality, they would continue walking for several days, and some, especially those who sustained any injuries or sprains, from falling from the wall for example, are the ones who would pass away,” he added. “So that’s an issue we’ve been dealing with for many years, but not just in the past, it’s happening now, too.”

The collaboration between the Consulate and Border Patrol developed into the Missing Migrant Program, which began at the Tucson Sector in 2015 and tasked the Border Patrol with doing a better job at tracking migrant deaths along the border.

About 1,900 Mexican migrants have been rescued since the program began, Barceló Durazo said. The remains of 380 other Mexican migrants have been recovered and identified.

The Border Patrol’s Missing Migrant Program, which began in Tucson, expanded border-wide two years later. De la Torre pointed to that program as an example of a best practice in one area being applied to other sections of the border.

In addition to piloting the Missing Migrant Program, Arizona continues as a testing ground for other border security and enforcement programs and policies.

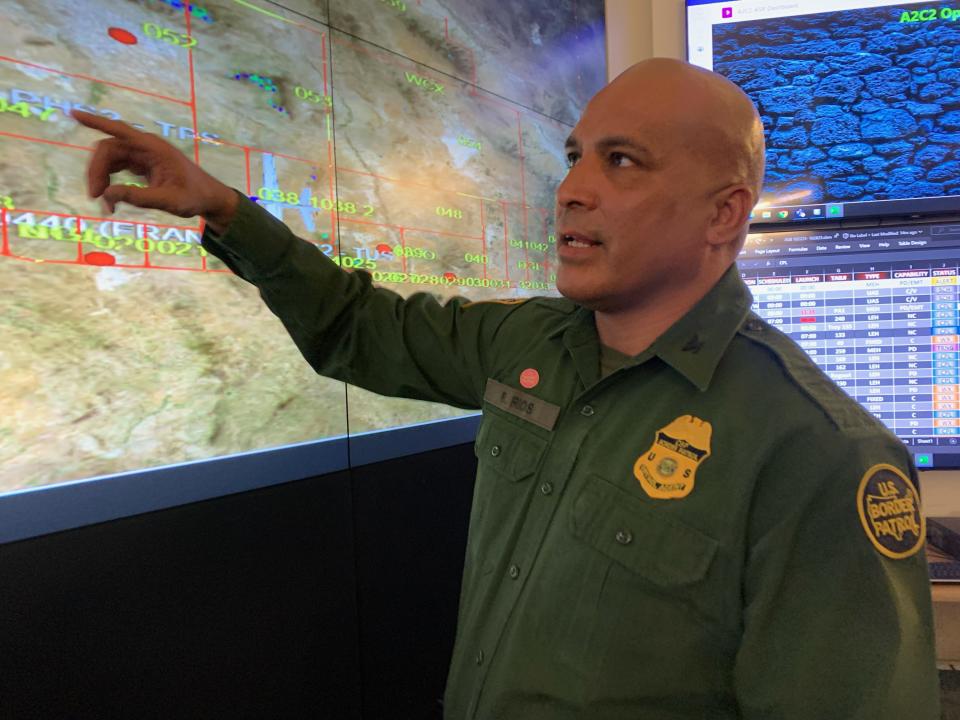

All emergency calls from lost migrants forwarded to the Border Patrol make their way to the Tucson Sector’s Air Coordination Center. It is the only center of its kind operating along the southern U.S. border.

Inside the sector headquarters in Tucson, the center is staffed at all times. Agents coordinate with nearly a dozen entities that have aircraft available and who regularly patrol different sections along southern Arizona. This includes local law enforcement agencies such as the sheriff’s offices; federal agencies such as Customs and Border Protection’s Air and Marine Operations; and even military branches in southern Arizona such as the Arizona National Guard or nearby Davis Monthan Air Force Base.

Ronaldo Rios, the acting director for the Air Coordination Center, said officials have access to the agencies’ flight schedules, as well as the capabilities available on each aircraft.

“That really streamlines that process of getting medical care out to the folks, whether it's for somebody that we've engaged that needs help, or for some of our own folks and potentially that help that are putting themselves in harm's way,” he said.

Humanitarian aid groups have gotten friction from Border Patrol

In addition to government efforts, numerous humanitarian aid groups also do searches and water drops on their own along the Arizona border. The exact number is unclear because many splinter from larger groups and start their own efforts.

Sometimes their work has caused friction with the Border Patrol. In the past, humanitarian aid volunteers faced charges for transporting rescued migrants in their own vehicles to get emergency aid or for littering after dropping off gallons in protected areas without permits.

The Border Patrol has even raided humanitarian aid camps along southern Arizona, accusing volunteers of harboring undocumented migrants, as they did in 2020 with the group No More Deaths. For their part, humanitarian aid groups have accused the Border Patrol of dumping or tampering with water supplies intended for migrants.

The situation at the Arizona border has cooled. Humane Borders says they are now more likely to face off with vigilante groups. They began locking the tanks and securing them in place, to make it harder for anyone to tamper with them. But they make it a point not to run afoul of federal or state laws.

“We're not allowed to transport individuals to a hospital. But we stay with them until Border Patrol arrives and give them water, try to help them cool down, give them some shade,” Cantillo said.

How are migrant remains identified in Arizona?

As the repository for the processing and collection of migrant remains, the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner has outgrown its current space. But a new $24 million facility is under construction and slated to open next year.

The building, located within the county annex on the south side of Tucson, was built in 1989 and has expanded over time. They added an outdoor cooler in 2005, for example, as the number of migrant remains recovered along the Sonoran Desert reached its first record peak, which would be broken time and time again over the next two decades.

“It's less efficient, right, because you're cooling multiple spaces,” Hess said. “So just one larger, more economically placed cooler will be much better for that. For just a large number of remains, we’ll have a better space that's not refrigerated, but it's just air conditioned, to house the unidentified remains that we’re retaining.”

The medical examiner has about 600 skeletal remains that have yet to be identified, as well as 900 remains that have already been cremated. Some of them have been retained for years.

Despite the nearly three decades of expertise that the Pima County medical examiner has developed in recovering and identifying migrant remains, there are still many challenges, especially with testing DNA samples.

“We'll go through these waves of building up this backlog of DNA samples that we have collected over a few years that we have no place to send them,” Hess said. “And then eventually we might get a grant to help.”

Grants, while helpful, are not a sustainable option, he added. They can make a big difference though.

Farther north in Pinal County, which is not on the border but still sees migrants trekking through the desert valleys, the medical examiner received in September a $500,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Missing and Unidentified Human Remains Program.

The funds will allow the Pinal County medical examiner to do DNA testing on 20 sets of remains at their facility that are unidentified. Suzi Dodt, the county’s medicolegal death investigator, said they likely are migrants who died crossing the border.

“Those are the hardest to identify, they're nearly always skeletal remains,” she said. “Photos from families and different types of tattoos or scars or marks that they have are no longer present to help identify them.”

The grant will allow Pinal County to collect about 240 DNA samples from families whose relatives went missing while crossing the border and will upload them to a national database for missing persons.

The Arizona Department of Public Safety also received nearly $850,000 under that same program to tackle a DNA testing backlog for more than 2,000 unidentified remains in Arizona, more than half of them are in Pima County. The money will allow DPS to hire two additional forensic staff for a three-year period, as well as equipment needed to carry out the testing.

For all of the advancements and coordination between local, state and federal agencies, and nonprofit organizations in Arizona, the full scope of migrant deaths remains difficult to understand.

The Government Accountability Office published a report last year saying the Border Patrol needed to improve the way it tracked migrant deaths through its Missing Migrant Program. Nobody knows how many deaths happen on the Mexican side of the border.

Hess acknowledged that the conditions in Arizona that allowed them to develop the system of reporting and identifying remains are very different than in other parts of the U.S. Southern border.

He said the inconsistency, in terms of funding and the attention paid to the issue, makes it harder to make a meaningful impact.

“We've been telling the same story over and over for years. And you know what? Nothing's changed,” he said.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Arizona border seen as model for migrant rescues, identifying remains