In Egypt, falafel is a breakfast food

Across the Middle East and Northern Africa region (MENA), falafel is served as a breakfast food and is usually prepared as a sandwich. Known as ta’ameya in Egypt, it's the meatless breakfast patty of MENA. Egyptian chef Moustafa Elrefaey of the world-renowned, Cairo-based chain Zööba explains that ta’ameya is a breakfast food for the same reason bacon is a breakfast food: grease.

“Sometimes you need greasy food in the morning to put a smile on your face,” he tells TODAY.com.

The bean-based balls are usually fried and make for a protein-packed meal to start the day. Falafel is inherently prepared vegan and gluten-free. In addition to its nutritional value, falafel is also an affordable street food.

“Ta’ameya is part of our identity and culture. We grow up seeing ta’ameya at the center of any family breakfast gathering regardless of your social class,” Elrefaey says.

There is hot debate over where falafel was invented, but the most widely accepted origin story is that this fritter originated in Egypt. It was possibly created by the Coptic Christians who abstained from eating meat during some religious holidays such as Lent. Another theory claims British officers who occupied Alexandria, Egypt in 1882 asked for fried vegetable balls similar to what they ate in India. Some folks believe that ta’ameya can be traced back to the era of pharaohs.

While the origins of the fried bean ball remain somewhat of a mystery, ta’ameya was likely the precursor to falafel, the national dish of Israel. Opinions vary over which country serves the best falafel, but there is no denying that ta’ameya is one of the most unique in the region, as it's not made from chickpeas like most other versions are.

In Egypt, the dish calls for dried fava beans (also known as broad beans). “Ta’ameya is made with crushed fava beans which makes it earthy and packs more flavor," says Elrefaey. "The fava beans make the fritter fluffier and highlight the spices and herbs in it."

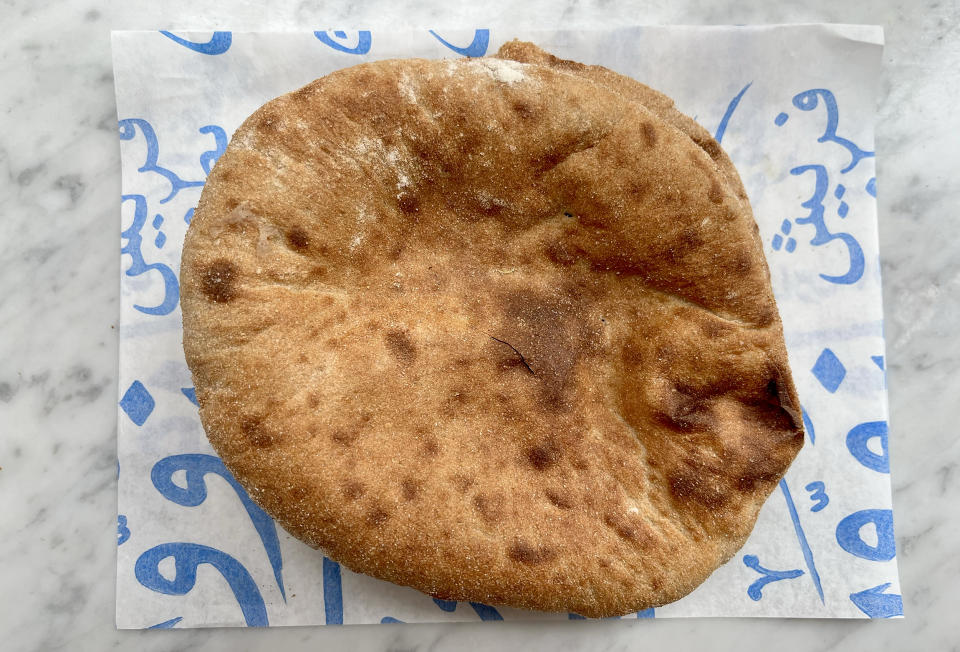

Fava beans used in ta’ameya provide a much creamier consistency and a more distinct flavor than chickpeas used in falafel. Ta’ameya is lighter and retains more moisture than falafel. The dough is less grainy but it gets crunchy on the outside when it is coated in sesame seeds and fried. Ta’ameya dough is pressed into a flat disc-like patty shape rather than a ball, which Elrefaey says fries faster in shallow oil. Ta’ameya is very flavorful as it is made using many herbs which creates a greenish hue in the dough.

“Falafel is everywhere, but I believe ta’ameya is more flavorful and works better than falafel in sandwiches, but it is not as popular globally. I wanted to introduce proper ta’ameya to the world and make it mainstream like falafel, so I opened Zööba,” Elrefaey says. The fast-casual Egyptian street-food chain has seven locations in Cairo, Egypt as well as outposts in Saudi Arabia and New York City. Over the last decade since opening, Zööba has won international awards for the best falafel including winning the London Falafel Festival in 2016, and was ranked No. 38 of the 50 Best Restaurants in MENA this year.

Making ta’ameya is a two-day process. The evening before you plan to cook the ta’ameya, leave a bag of dried fava beans soaking overnight (8 to 15 hours) in several inches of water. To save time, use dried split fava beans (yellow) rather than whole fava beans (brown) which would require skinning after soaking. When making the dough, use fresh herbs (parsley, cilantro, leeks) rather than dried variations.

Ta’ameya is served in warm baladi bread, which is still prepared today in a method similar to how the traditional bread was baked by ancient Egyptians around 3,500 years ago. The National Museum of Egyptian Civilization in Cairo has a display of circular wheat flour loaves found in the tombs of Deir el-Medina near Luxor from 1295 B.C.E., and the tools used to grind the emmer wheat into flour. Ancient Egyptians even made tiny figurines of people baking bread.

While it is unclear if the bread was being served with ta’ameya in Ancient Egypt, today the sandwich comes with an assortment of accompaniments such as raw tomatoes and onion and then drizzled with tahini. Elrefaey’s favorite way to eat ta’ameya is to put two discs in baladi bread with a dash of salt on top. “It is very simple but this way you get all the flavors out,” he says.

Often ta’ameya is served with a side of pickled vegetables. Zööba offers three options — classic with arugula and tahini, pickled lemon and beets, or spicy with roasted harissa cauliflower. But what sets Zööba apart are the sauces including a delicious and vibrantly colored beetroot hibiscus tahini and bessara — a mixture of fava beans, onion, garlic, cilantro and crispy onion.

This article was originally published on TODAY.com