El Niño likely in 2023. Here’s how it differs from La Niña, what it means for the PNW

Just as three consecutive La Niñas finally stop affecting global weather patterns, conditions in the swirling waters of the Pacific Ocean strongly suggest an El Niño could arrive in the coming months, weather experts say.

The World Meteorological Organization, an arm of the United Nations, estimates the likelihood of an El Niño developing in May or June at 60%, with the probability increasing to 80% by October.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has predicted a 61% chance that an El Niño will be in place by August through October.

What is El Niño and how will it impact the Pacific Northwest?

El Niños and their opposites, La Niñas, are naturally occurring weather phenomena that usually appear every two to seven years as a function of how the Pacific Ocean interacts with the air above it.

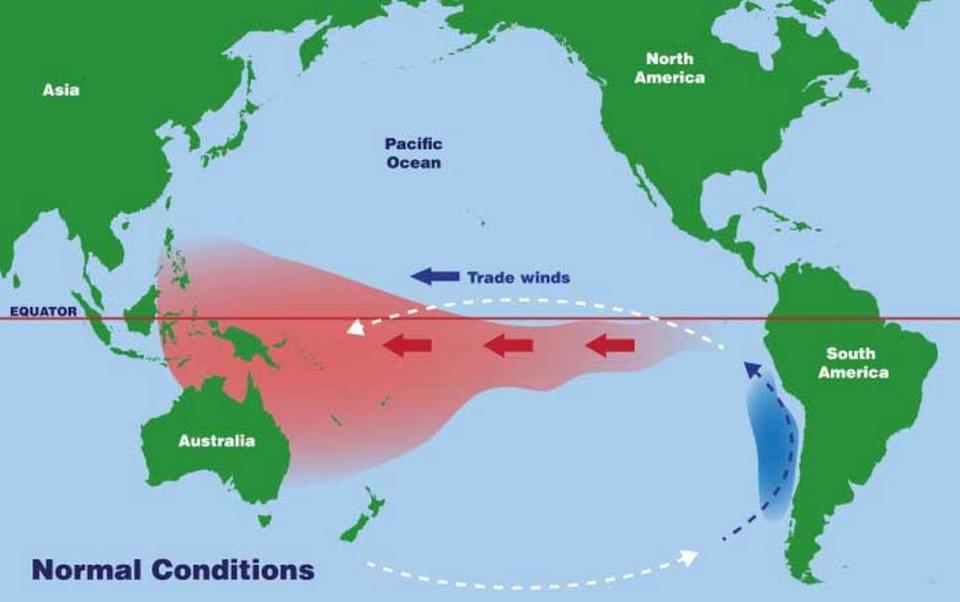

El Niños happen when the Trade Winds — winds that blow along the equator, east to west over the Pacific — weaken, causing the warmer water to move east toward South America, accumulating there before moving north to California and south toward Chile, according to NOAA.

In El Niño years, NOAA says, rain clouds form over the warm ocean water and move inland, dropping more rain than usual in South and Central America and the U.S.

During an El Niño winter, the Pacific Northwest is usually drier and warmer, while the southern U.S. will experience wetter-than-usual conditions. El Niño doesn’t have as big of an impact on the Pacific Northwest in the spring and summer, National Weather Service meteorologist Joel Tannenholz told McClatchy News.

“There are too many other factors in weather to say that El Niño is directly responsible this far north,” Tannenholz said.

How do El Niño and La Niña differ?

A La Niña happens when the Trade Winds are abnormally strong, sending warm water from off of South America, in the eastern Pacific, toward Asia and Australia, in the western Pacific.

As the warm water moves west, it takes tropical rainfall with it, disrupting the normal circulation of the atmosphere and affecting jet streams.

El Niño occurs when the jet stream dips further south than usual in the Pacific, amplifying the storm track across the southern U.S. and Central America, but keeping stronger tropical moisture away from the north.

During a La Niña, it’s typically wetter and colder in the Pacific Northwest throughout the winter. La Niñas and El Niños can also affect the Pacific hurricane season, which runs from June through November; La Niñas result in colder water and less intense hurricanes, while El Niños can result in stronger and more frequent storms, Tannenholz said.

How does El Niño affect storms and hurricanes?

Forecasts for the 2023 hurricane season vary. The University of Arizona’s yearly forecast calls for up to nine named hurricanes, as many as five of which could be major hurricanes with Category 3 winds or higher.

“We expect a good, nice El Niño to come back after a few years of La Niña,” stated Xubin Zeng, University of Arizona professor of hydrology and atmospheric sciences, in a news release.

La Niña conditions have occurred for three straight years, for only the third time in recorded history. The other two times were from 1973 to 1976 and 1998 to 2001.

“It typically ping pongs back and forth, in general, from one to neutral to the other and back,” Weather Service meteorologist Dave Groenert told McClatchy News. “Sometimes you do get return years, but to get a third return year, I don’t know if anyone really knows why that’s the case.”