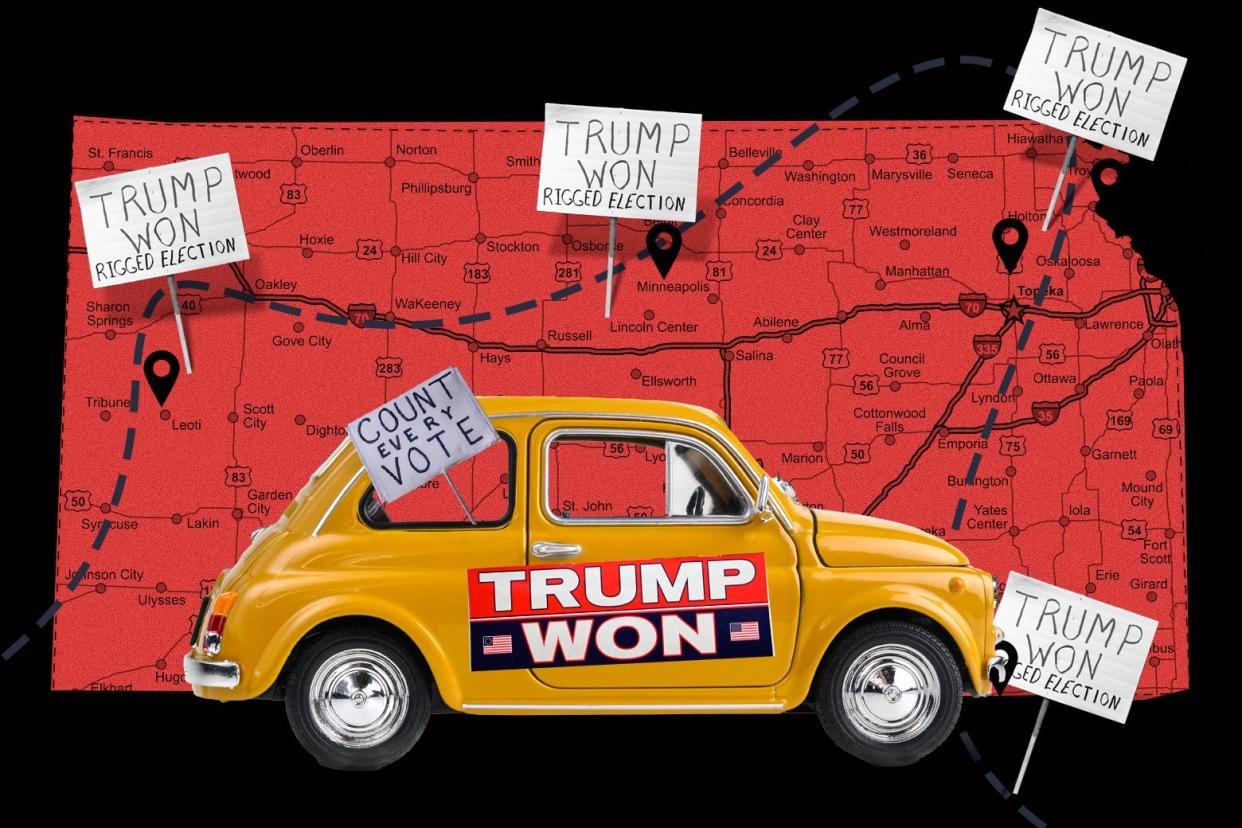

Election Denialists Have Taken Their Show on the Road

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The Kansas Legislature hosted an odd contingent last month. Proponents of QAnon conspiracy theories, lobbyists from conservative “dark money” groups, and vigilantes willing to take covert action to find proof of election crimes showed up for a two-day forum to present on such topics as “Election Machine Vulnerabilities,” “Voter Roll Maintenance,” and “Ballot Harvesting.”

Speakers probed questions like: Is the governor “secretly coordinating with the Biden White House to undermine Kansas elections?” At one point, a prominent conspiracy theorist and Twitch streamer—known as one of the Trump camp’s key election denial “sources”—was scheduled to speak. (It appears that her invite was later rescinded.)

Because the session was an invite-only event, actual election administrators and legitimate voting rights groups such as the League of Women Voters were shut out of the proceedings. So, for two days, Kansas legislators were treated to hours and hours of conspiracy theory propaganda.

And yet, the session was such a minor news event that the coverage remained limited to stories in the state press that fact-checked the misinformation. It did not make national news at all.

The smallness of this story—of conspiracy theorists getting exclusively invited to address the most powerful legislators in a state, representing themselves as “experts,” and monopolizing lawmakers’ attention, years after the 2020 election—shows just how endemic and downright ordinary the election fraud conspiracy theory movement has become in the U.S. since 2020.

It also shows how the movement persists.

Election denial conspiracy theorists are still very much banging the drum—and not about legitimate threats to voting systems, like the kind uncovered by the Washington Post and Fani Willis’ sweeping RICO indictment of Donald Trump and 18 alleged co-conspirators. Instead, they are pushing the same baseless ideas about foreign meddling, rigged results, and Democrat nefariousness that fueled the Jan. 6 Capitol riot.

“Looking back at the energy in 2021, after the election—it broadly has subsided,” said Daniel Griffith, the senior director of policy at Secure Democracy USA, a legitimate voting rights and election integrity nonprofit. “But there is some vocal shrinking minority of folks who are throwing a lot of energy at this stuff still. In pretty much every state, you have at least a couple legislators who will entertain their ideas and introduce bills. I don’t think it’s going away.”

Many of the speakers at the Kansas Legislature subscribe to outlandish views.

Greg Shuey, the president of a group called the Liberty Lions League, is, for example, a proponent of a theory known as “Italygate,” which holds that during the 2020 election, an Italian defense contractor, working with senior CIA officials, uploaded software to military satellites to switch votes from Trump to Biden. (In variations of this theory, the Vatican also played a role in helping to switch the votes.)

“We are asked to trust companies that have direct and indirect relationships with our foreign adversaries while being denied the ability to really see what we have bought and are using for our elections today,” Shuey said in his presentation. “Why would anyone think that Kansas is immune from machine manipulation?”

Appearing via video call was Clint Curtis, a programmer who has long claimed—highly implausibly, given several patently false details of his story—that he was hired by a Republican politician to spy on NASA and separately to write a code that would “control the vote” in West Palm Beach, Florida, in 2000. Curtis unsuccessfully ran for Congress in 2006 and 2008 and has continued to push dubious claims about vulnerabilities in the technology. At the session, he presented his story again. “This is why you can never trust computers,” he said.

Thad Snider, another presenter, was one of six plaintiffs to file a lawsuit in federal court in Kansas pushing to invalidate the 2020 election, arguing that the Chinese government could have tampered with the elections through servers based in China. At the two-day event, he expounded upon the dangers of laws that allow third parties (usually volunteers or campaign workers) to collect ballots from voters’ homes, and other perceived nefarious efforts, citing debunked but viral videos that “proved” there were incidents of ballot stuffing and other forms of tampering. “I don’t trust the government,” he said. “I trust the people, and we will go through this ourselves, and we will watch it and make sure that it’s right.”

Mark Cook—an IT worker who has been a featured guest on MyPillow CEO Mike Lindell’s show Lindell TV to promote the theory that Dominion Voting Systems rigged the 2020 election—also appeared at the event. He has the distinction of having actually participated in potential crimes related to voting.

Cook has previously been accused of helping an elections clerk smuggle data out of voting machines in an effort to try to find evidence of hacking. It doesn’t matter that his scheme ended up implicating him in potential crimes rather than exposing others; he sticks to his belief that the 2020 election was stolen. “Think about that: What does dominion mean?” Cook said at the Kansas session, referring to Dominion Voting Systems. “They want to have dominion over us. We need to open our eyes.”

At least one conspiracy theorist—a zany and dangerous character called Terpsehore Maras, also known as Tore Maras—proved too divisive to keep on the roster for the Kansas Legislature event. A Twitch streamer and QAnon conspiracy theorist with a number of other names, Maras is perhaps most infamous outside the election-denying community for putting on a benefit concert in 2018 in North Dakota called “A Magic City Christmas,” ostensibly to benefit homeless shelters and buy wreaths for veterans’ graves, only to then pocket the money.

But Maras’ more political work raised her public profile in 2021. She has, at various points, run to be Ohio’s elections chief; organized a national scheme to have QAnon supporters run for office; and pushed her followers to try to dig up dirt on elections officials. (Maras’ QAnon content on Twitch has been financially fruitful; her fans once donated more than $100,000 to a GoFundMe for a new car.) To lend credence to her various campaigns, Maras falsely claimed, at various points, to be a medical doctor and to have a Ph.D., and she made dubious claims to having an intelligence background.

These claims wound up in one notable document: In a lawsuit to try to overturn the 2020 election, Trump lawyer Sidney Powell, one of several people indicted over potential election fraud in Georgia and a leading voice of the Dominion Voting Systems conspiracy theory, cited “a private contractor with experience gathering and analyzing foreign intelligence” who knew of a plot to rig the U.S. election. That source, the Washington Post reported, was not a private contractor with experience gathering and analyzing foreign intelligence but Maras herself. (Maras appears to have been disinvited to the Kansas Legislature shortly before the event itself.)

Still, perhaps the most dangerous speakers at the two-day event were the polished “experts.” At one point, two lobbyists took the floor to speak about state and federal “agency involvement in voter registration and legal issues”—meaning untoward government interference in the state’s elections. The two lobbyists, who live not in Kansas but in Maine and Virginia, represent a conservative organization based out of Florida that has supported welfare restrictions and campaigned for the elimination of ballot drop boxes. They had a pointed question for the lawmakers: Why was the governor, Democrat Laura Kelly, hiding the agreement she made in a “backroom deal” with voting rights nonprofits, without lawmakers’ knowledge, on matters concerning voter registration? Was it because the “deal” was plainly meant to register more Democrats?

“These deals are hidden from the public as well as this Legislature until they are disclosed by others months or even years after the secret deal has been made,” one of the lobbyists said.

This was plainly false. During the Legislature’s lunch break an hour later, the Kansas Reflector requested copies of the agreement, and the office of the governor, the secretary of state’s office, and one of the voting rights nonprofits each forwarded the Reflector a copy—quickly and without a fee. The 2021 agreement was nothing more than standards that brought the state into legal compliance with the National Voter Registration Act. Nothing had been concealed.

But it’s easy to see how these lobbyists’ implications could take root, in the minds of the aggrieved, and then become amplified beyond the statehouse.

The session in Kansas was only the latest in a string of such conspiracy-laden hearings in the Legislature over the past several years. But Kansas isn’t the only place where this activity is continuing after last year’s midterms. In late January, for example, a state Senate election committee in Arizona invited a group called “We the People AZ Alliance,” an organization that once tried to recall the Maricopa County supervisors, to give presentations at two separate formal meetings of that state’s Senate Elections Committee. Misinformation from those presentations appeared as the basis for a number of bills that were eventually passed, though Democratic Gov. Katie Hobbs vetoed them.

In 2022 an NPR report found that over the previous year and a half, four election denial influencers—Mike Lindell being the biggest among them—had appeared in more than 300 events across 45 states and D.C., often with elected officials and political candidates. The Election Integrity Network, run by the conservative activist and election denial scheme leader Cleta Mitchell, has been mobilizing election denial efforts across different states, including Kansas.

“We do know there’s multistate orgs that are coordinating these efforts and providing ideas to the folks,” said Griffith, the Secure Democracy USA policy director, referring to election denial activists. He noted that a lot of the language in various bills proposed in different states sounds familiar, as much of it is rooted in the same conspiracy theory claims.

“Every state will have a bill that limits voting machines or ballot drop boxes or other supposed integrity aspects. It’s the same ideas everywhere, even though each state runs their election individually and has their own experience,” he said.

Wendy Weiser, the director of the Democracy Program at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law, also spoke about “an interdependent network” of individuals who are pushing these ideas at the state level. “Those who come testify are often the same people who are driving those strategies,” she said.

That the lineups include few to zero voting activists with real expertise doesn’t seem to matter. At least, it didn’t bother state Sen. Mike Thompson, the Kansas legislator who chaired his state’s bogus committee on elections. “It’s not about the expertise but I think you look at, for example, the work some of these people have done and they’ve committed huge amounts of time,” Thompson told the Kansas City Star. “Experts don’t necessarily come with a degree after their name or a company name to back them up.”