Election workers navigate increasing controversy, scrutiny

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

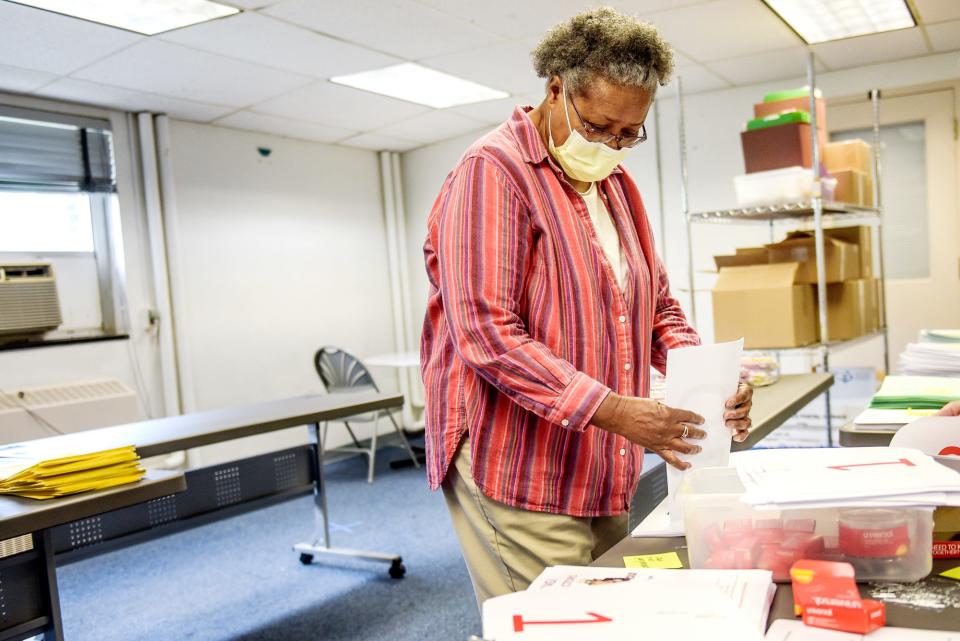

LANSING — For about 15 years, Janet Glisson has served as a precinct worker in Lansing, helping thousands of people vote on Election Day.

In 2020, she coordinated the Cumberland Elementary School precinctwith her granddaughter, Abigail Wiefreich. This year, at Wiefreich's urging, she moved behind the scenes to work with the city's absentee ballot counting board because of concerns about safety.

"Because of the (2020) election — the presidential election was so volatile — she didn't want me to work in the precinct," Glisson said as she compiled instruction manuals for this year's precinct workers. "She said, 'Seniors don't need to be here.'"

Election day is less than two weeks away, and election administrators and inspectors have been preparing: navigating several turbulent years, changing processes, fight a lack of election infrastructure, a pandemic and a right-wing movement casting doubt on election security.

Officials say some Republican election deniers, continuing to push former President Donald Trump's debunked claims of widespread fraud in the 2020 election, have sought to mobilize party members as election challengers and poll watchers. Some have even encouraged supporters to become election workers so they can search for evidence of what they perceive to be wrongdoing.

"The Republican Party seems to be recruiting individuals to serve as precinct workers to be employed by the local clerk and to serve as spies or moles for that party, by sneaking in cellphones, pens, calling Republican lawyers throughout the day, all of which is unacceptable behavior," Ingham County Clerk Barb Byrum, a Democrat, said.

Linda Marquardt, vice chairperson of the Eaton County Republican Party, said her county party hasn't coordinated any efforts for members to act as poll watchers or election challengers, but she knows of people who are looking to observe the process on their own accord.

"I think everyone can agree we want to reduce the potential for any nefarious or fraudulent activity. The goal should be that everyone has trust in our election process," Marquardt said.

Election workers are expected to be nonpartisan, something Lansing officials, like election supervisor Robin Stites, make clear to new workers at mandatory training sessions. For midterm elections, Stites said, the city employs about 650 workers. Clerks are supposed to strive for parity among workers' party affiliations, and in Lansing, Democrats and Republicans pair up when completing tasks.

"There's no partisan politics in the precinct ... You are an employee of the city during that day and so, therefore, subject to the same rules," Stites said. "All of this is what we went over with all of our workers. We had a few people we followed up with on (primary) election day, just to kind of reiterate that process."

But rules for what elections challengers can do are still in question after a judge Oct. 20 struck down instructions for election challengers created by the Bureau of Elections.

The order from Michigan Court of Claims Judge Brock Swartzle marks a legal victory for the Michigan GOP and Republican National Committee, which brought the lawsuit challenging the legality of the election challenger manual issued by the Bureau of Elections this year.

Swartzle's order bars election officials from using the manual and requires Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson and Michigan Elections Director Jonathan Brater to rescind the manual or revise it to comply with Michigan election law.

Swartzle found that some of the provisions in the manual such as a ban on the use of electronic devices at absentee counting boards were at odds with the law or failed to undergo the proper rule-making procedure with input from the public and state lawmakers. He wrote that Benson and Brater "exceeded their authority with respect to certain provisions" in the challenger manual.

Officials wary of election deniers

This year, in Kent County's Gaines Township, near Grand Rapids, a Republican-affiliated election worker stuck a personal USB drive into an electronic poll book — a computer storing voter registration data, including confidential, personal information about all voters in the precinct. Kent County Clerk Lisa Posthumus Lyons told the Detroit Free Press last month in a statement that the breach did not result in any access to voting machines and no results were affected. The compromised equipment was withdrawn from use.

Elections officials from Lansing, Ingham County, Charlotte and Williamstown Township said they haven't seen any suspicious behavior by poll workers in recent elections, but they have seen an increase in the number of election challengers.

Byrum said, typically, if a prospective poll worker has ulterior motives, officials find out based on how they interact with training — which is required for new workers. Under state law, workers must attend local training or pass a locally administered exam every two years in order to serve.

“I have been encouraging my local clerks to remember that they are, in fact, the employer of precinct workers, and may certainly relieve someone of their duties if they are violating their oath of office or being insubordinate,” Byrum said.

In Michigan, registered voters can be credentialed as election challengers by political parties or other groups to inspect precincts and absentee ballot counting boards, as long as they don't impede the process.

Non-credentialed observers also can act as poll watchers. According to a Secretary of State manual, challengers and watchers play a "constructive role" in the process, though only challengers can call into question a voter's eligibility or the way inspectors operate a polling place — provided they do so with specificity and clarity.

Charlotte Clerk Mary LaRocque, whose position in non-partisan, said the city hasn't dealt with any election challengers or poll watchers, but she expects them to be on hand for future elections.

During August's primary, Williamstown Township Clerk Robin Cleveland said, poll watchers challenging election workers was a constant at the township's two precincts.

"Every time I was in the precinct, there was one of our workers being challenged by a voter over something," Cleveland, a Democrat, said. "(Workers) have to be more on top of their game."

Concerns about voter intimidation led Byrum, Ingham County Prosecutor Carol Siemon and Ingham County Sheriff Scott Wriggelsworth — all Democrats — to issue a press release Thursday, assuring voters that law enforcement will address any instances of threats at polling places.

Resources — including time — are at a premium

One target of right-wing election deniers has been no-reason absentee voting, which was approved in November 2018 by nearly 70% of Michigan voters. Clerks say the process — which allows all eligible voters to request and cast ballots early through the mail or at designated ballot drop boxes — has made voting more accessible.

In 2020, absentee voting became the most-used form of voting in Ingham and Eaton counties. In 2020, 64% of Ingham County voters and 54% of Eaton County voters opted for absentee ballots. In this past August’s primary election, Ingham County's total rose to 67% of those casting ballots.

That year, voting at the polls was still the dominant method in Clinton County, where 85% of voters cast their ballots in person on Nov. 3.

Your guide for November:Here's what you need to know about the Nov. 8 general election in Greater Lansing

More:Here are the rules Michigan poll watchers, election challengers must follow

Because of the surge in use of absentee ballots, many municipalities have appointed absent voter counting boards to handle them. Byrum said local clerks have had to divert resources from precincts where in-person voting takes place. Ingham County itself invested funds in high-speed ballot scanners, envelope openers and other technology to facilitate the process, the clerk said.

Not all municipalities have the resources to obtain such equipment, like Williamstown Township.

Cleveland said the municipality, which has a population of just more than 5,000, could use another tabulator machine to count absentee ballots. Right now, they have three — one for each precinct and one for their absentee counting board, despite the increase in absentee ballots. But they cost $5,000 — "a lot of money for a small township," she said.

Under a Michigan law passed last month, only cities and townships with a minimum population of 10,000 can pre-process — but not count votes from — absentee ballots, starting two days ahead of August primaries and November general elections.

With the new law, Williamstown Township still doesn't have the option. Not being able to count early complicated matters in 2020, when Cleveland and her staff worked until 5:30 a.m. Wednesday morning. It also means election results trickle in later.

"That's an arbitrary number," Cleveland said. "People with 10,000 voters have more people working elections than the smaller jurisdictions like us, so it doesn't help us with our flexibility."

While a new tabulator would help, though, Cleveland said what the township needs most is more labor.

The typical profile of an election worker in Ingham County, Byrum said, tends to be women who are 50 to 80 years old.

Cleveland said many of her older workers stayed home during the pandemic. She's been able to find replacements to work at precincts, but they need more workers processing absentee ballots. Currently, Williamstown Township has about 20 part-time election workers, including herself, operating two precincts and an absentee voter counting board. Under state law, three workers must operate a precinct at all times. Cleveland aims for seven workers at each precinct, leaving only six workers to process absentee ballots.

“And it can't just be anybody. It has to be somebody who is able to work with computers, who's able to be very detail oriented to check signatures … there’s just a lot of nuance to elections,” Cleveland said.

More:Lawmakers pass series of election bills following negotiations on preprocessing ballots

More:Fact-checking allegations of misconduct against Benson: What we found

'We're pretty good PR people'

Overall, elections officials and workers — including clerks and part-time volunteers — say they welcome anyone with doubts about security to alleviate those concerns by being a part of the process.

Jayson Gillespie is a Michigan State University political science major and an intern for the Lansing Clerk Chris Swope's office. He said he hopes more skeptics sign up to work for their local clerk's office.

"To a certain extent, let them (challenge)," said Gillespie, as he verified one-by-one that signatures on voters' ballots matched their voter IDs. "We're not hiding anything here. There's no big conspiracy going on. They're more than welcome to come and have more confidence in the system."

In their communities, workers say they find themselves addressing concerns among people who are skeptical of the electoral system.

For Myrna Mitchell-Withers, that's not an entirely new experience.

A former public school teacher, Mitchell-Withers started working elections in 2012 during former President Barack Obama's re-election campaign. At her precinct, she helped many people who had never voted before, and only wanted to shade in one bubble at the top of their ballots for Obama.

Since then, she's functioned as a liaison for people in her life who are concerned about whether their absentee ballot will be counted.

"I say it's just as trustworthy as going to the precinct," Mitchell-Withers said.

On Oct. 19, a roundtable of six longtime Lansing election workers, including Glisson, said they also often occupy the same role in their communities. Sometimes, they said, it's helpful for people to hear the electoral process explained by a familiar face.

"I think we're pretty good PR people," Glisson said. "I have friends and family who will ask questions on the process ... when I explain how it all does, the whole process and how it's counted and recounted and there's so many people handling it, they feel more reassured to doing it."

Wiefreich has worked elections with her grandmother since she was 16. She said it's important for everyone to have experience working elections, but especially those with concerns.

"People just think that they know what they're talking about, and can so easily be like, 'Ballots are coming from nowhere, people are voting multiple times.' But until you see what's actually going on — how many things there are going on that fact check, double-check and make it so that isn't possible — you wouldn't know," Wiefreich said. "You kind of learn (about it) when you're in high school, but not really."

Detroit Free Press reporter Clara Hendrickson contributed. Contact reporter Jared Weber at 517-582-3937 or jtweber@lsj.com.

This article originally appeared on Lansing State Journal: Michigan election workers navigate increasing controversy, scrutiny