Elections are public's voice. NJ voters must finally be able to initiate ballot questions, too.

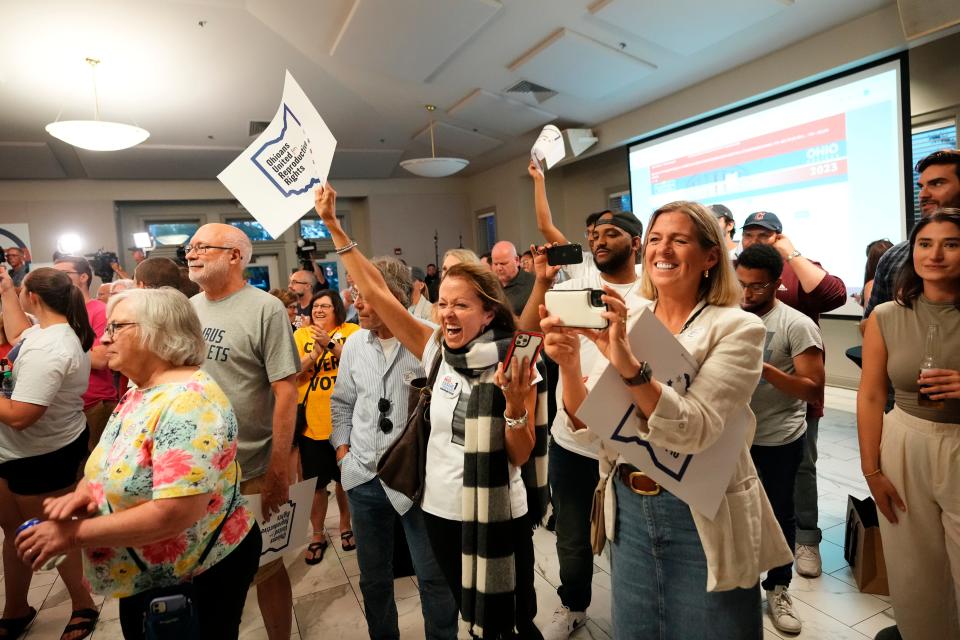

It clearly surprised Ohio Republican leaders that so many people turned out in an August special election. Ohio Secretary of State Frank LaRose scheduled the vote in a traditionally low-turnout month in hopes of heading off the coming ballot question in November on rolling back some of Ohio’s recent laws that curtailed legal abortion options. But many Ohioans are angry about these drastic new abortion limits, and they intended to show that by using their power — preserved in the recent vote — to change their state constitution by simple majority votes on public ballot questions.

Progressives across the nation are celebrating this “victory for democracy.” But, while it is good that in Ohio, the partisan trick to raise the constitutional amendment margin to 60% failed, the critics were right on one thing: considered apart from the cynical stratagems in this case, there is something very odd about this much popular power to (a) put a question on the ballot through a popular petition drive, (b) without the legislature’s approval, that (c) will, if approved by 50.1% of voters, change the state constitution — as opposed to making an ordinary state law that, as in Alaska and Wyoming, statehouse majorities with the governor could amend after two years.

This is certainly not what Madison, Hamilton and other framers of our federal Constitution thought “republican government” required, when their document guaranteed that every state must have one. They believed that it should be harder to change constitutional law than ordinary statute, which should be controlled by simple majorities in representative legislatures (which is why they never imagined, and would have opposed, a filibuster in the federal Senate). Of course, they also did not expect statehouse districts, including Ohio’s, to be so gerrymandered as they now are.

It takes 60% in both chambers of the Ohio Legislature to put a proposed constitutional change on the ballot for approval by Ohioans. It is the same in New Jersey, except that the state Legislature can also pass a proposed amendment by simple majority in two subsequent years and then it goes on the ballot for popular approval (see IX §1 of the New Jersey constitution). For example, in 2021, the Statehouse in Trenton passed both the amendment to allow sports betting on college athletes and the amendment to allow charitable organizations to raise money by holding raffles. The former was rejected by the public, while the latter was approved.

The result is that, in Ohio, a public petition process may be an easier route than going through the elected Legislature, whereas New Jersey lacks any public initiative option, and there is not yet any grassroots drive to get the state government to establish one.

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, 15 states allow public petition drives to place on the ballot questions that, if approved by the general electorate, will amend the state constitution. But not all of them allow a simple majority of voters to approve proposed amendments. In three other states, including Ohio, Michigan and Nevada, the Legislature gets a chance to enact a detailed law implementing the theme of a successful petition drive. If it does not, the question then goes on the ballot. But in Nevada, for a constitutional amendment to pass when it comes from a petition drive rather than from the Legislature, it must be approved by a simple majority of voters in two subsequent elections.

Moreover, while pro-democracy reformers also point to Michigan’s public-initiated amendments in 2022 to strengthen voting rights, they rarely seem to focus on several deep blue states that do not allow direct public petition drives to put any questions on the ballot. Like my home state of New Jersey, Vermont, Maryland, Hawaii, New York and Rhode Island allow no popular initiative process to force a question onto the ballot, even to make an ordinary state statute.

On a radio show in May, I challenged New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy to urge the Democratic-controlled state Legislature to place a question on the ballot in 2024 concerning whether to keep the Mount Laurel ruling by the New Jersey Supreme Court. This ruling has become a vehicle for builders to force small towns to let them put up five- to six-story buildings, in which a mere 10% or 15% of units are designated as “low-income.” He flatly refused, because he knows that voters would probably repeal the Mount Laurel regime. Then he and the Statehouse would have to do all the hard work to create a much better low-income housing program that could focus on rebuilding the most blighted and impoverished neighborhoods in New Jersey’s larger towns and cities. For the same reason, the Statehouse majority in Trenton does not want to establish a petition process for New Jersey residents: they want to monopolize all control.

This is not to deny that there are problems with public petition drives. They have to have limits and complex review standards to work well, as Ohio’s process illustrates. In my book, "The Democracy Amendments," I discuss the criticism that petition drives sometimes reflect more the priorities of special causes popular with rich NGOs, celebrities and rich donors than the highest priorities of the general public.

California is notorious for this phenomenon. But then, state legislatures also cherry-pick the topics they send to voters, and the role of big donors is less visible in their case too. New Jersey’s Statehouse will not put that Mount Laurel question on the ballot, but they were happy to kick the marijuana legalization question to the general public so they did not have to approve it directly.

Transparency in NJ elections: NJ ELEC just tossed 107 cases. What did we expect from 'reform'?

Garden State open records: NJ can't scrap OPRA. Murphy and the Legislature need to save it

My book also considers whether there should be national ballot questions, perhaps in presidential election years, to change a federal law, or even to send a constitutional amendment to the states for ratification. For example, American voters would almost certainly vote to jettison the filibuster — probably by over a 60% margin, although this would not need to be a constitutional change.

I also consider whether three-fifths of the states (30), acting together, should be able to place one or two bills on the federal House and Senate agendas that must get a final vote each term. This would enable public petition drives across many states that allow them to have an indirect impact on the agenda in Congress.

Overall, the book develops 25 such structural reforms to the Constitution, including nonpartisan national election standards, banning the filibuster, and instituting strong anti-corruption requirements, that would strengthen American democracy. Ohio’s experience certainly proves just how much Americans across the political spectrum are yearning for fundamental and pro-democracy changes.

John Davenport, a resident of Caldwell, is a professor of philosophy and Peace and Justice Studies at Fordham University. He can be reached at davenport@fordham.edu.

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Ohio's Issue 1 election results could impact NJ – just not on abortion