Elena Ferrante's 'Lying Life Of Adults' Is A Story Of Innocence And Experience

The further one gets from one’s own adolescence — the dreams, the heartaches, the haircuts — the harder it is to see it as anything other than mildly ridiculous. Why did you dedicate reams of dreary diary entries to a monosyllabic teenaged boy with curtains who never so much as glanced at you (hi there, Joe Collinson!), or spend hours in front of the mirror scrutinising the many faults of your face (spoiler alert: they get worse!). You know absolutely that it all seemed gravely important at the time, but the feelings, as the years pass, become cloudy and far away.

It is novelists who stand the best chance of getting us back there, to the age of euphoria and narcissism, when the world revolved around and in us. And it’s perhaps only novelists who can attempt to do so with a straight face. The success of Sally Rooney’s Normal People is testament to the potency of portrayals of this difficult age — although her knack and penchant for sex scenes probably help. (See also, in a private moment, the recent BBC adaptation of that novel.)

The accurate and evocative depiction of adolescence is also a significant factor in the fierce devotion inspired by the works of the Italian writer Elena Ferrante and in particular My Brilliant Friend, the first book of her Neapolitan Quartet, one of the out-and-out literary sensations of recent times. Ferrante’s young people experience emotions at supernatural pitch; there is no slight that is not devastating, no passion that is not all-consuming, no betrayal that doesn’t ricochet for decades. Never have the travails of adolescence been so eloquently legitimised.

For her newest novel — which prompted overnight queues when it was published in Italy last year, and is out here in September — Ferrante is back on this fruitfully unstable ground. The Lying Life of Adults opens with the narrator, Giovanna, recounting a pivotal moment in her early life: one that appears as initially slight to the reader as it is reportedly meaningful to her. One night, she overhears her father telling her mother that Giovanna is “getting the face of Vittoria”, his estranged sister, a wicked aunt whose malign influence Giovanna has been thus far spared. But the mysteries of Aunt Vittoria — the woman her father despises so much, the woman the teenage Giovanna feels she is destined to resemble, and not just facially — is too much. Vittoria becomes an obsession for Giovanna, and then, a quest.

Readers of Ferrante’s work will not be surprised to learn that Giovanna’s pursuit of her aunt is also a descent, both geographical and Dantean, from her usual territory in the “highest part of Naples”, which extends only as far as the leafy, hillside neighbourhood of Vomero, “down, and down” to the darker, poorer, scarier and nameless parts of the city, from which her uptight, intellectual parents have also sought to keep her. Here is where, as the novel progresses, the tenets of Giovanna’s life, everything she thinks she understands about human behaviour, will be undermined and overthrown, and where her Aunt Vittoria, grief-stricken and ferocious, is waiting.

Giovanna becomes bewitched by her aunt’s dramas, and befriends the three children of Vittoria’s married (but now dead) lover, Enzo, over whom Vittoria continues to exert a powerful and not entirely benign influence. As a consequence, she starts to uncover the lies that her own parents have spun her — sometimes to protect her, sometimes to protect themselves — and also to understand the power that telling lies can bestow. As the slightly awkward English title of the book suggests, learning that you can manipulate the truth is part of growing up, a way to rebel against those who have circumscribed your world, and to define its parameters anew.

Oh, and did I mention the sex? Like all adolescent protagonists from Jane Eyre to Adrian Mole, Giovanna is driven by a need to give herself, bodily, to someone, though she can’t quite decide who. Enzo’s younger son Corrado, who is vulgar and keen? His friend Rosario, who has a car and apartment and creepy teeth? Roberto, the boyfriend of Enzo’s daughter, Giuliana, a handsome religious scholar who spots Giovanna’s own intellectual brilliance (although we are informed, by-the-by, that she is also blessed with prodigious breasts)?

The Lying Life of Adults is being adapted by Netflix — My Brilliant Friend, before it, was made into two series for HBO — and contains savage observations about class, and the permeability of identity, with characters often forming relational trios that echo and overlap in intriguing ways. But if we’re honest with ourselves, Giovanna’s burgeoning love life is the underlying energy of the novel, the intrigue that keeps us hooked. In the meantime, she is getting to know herself bodily too. Masturbation she considers “a reward for the unbearable effort of existing”, in the way that only a teenager can: “It seemed to me that the desolate creatures destined for death had a single small bit of luck: alleviate the suffering, forget it for a moment, setting off between their legs the device that leads to a little pleasure.”

It might be tempting to ascribe the curious nature of some of these descriptions — compared, say, to the sensuousness of Rooney’s — to the act of translation (although Ann Goldstein, who has translated all of Ferrante’s works into English, does so again here with precision and poise). Yet the distancing quality of translation, the measured, formalising effect, is in some ways fortuitous: is puberty not, after all, a time when we feel disassociated from ourselves, like aliens in our own skin? Like us, Giovanna also experiences the distancing effect of language more literally: her new acquaintances speak Neapolitan dialect. “What a pity to be the last to arrive, not to speak the language they spoke, not to have true intimacy,” she reflects.

Elena Ferrante is famously a pseudonym, the real author’s identity a much-speculated-upon secret. But she (although occasional arguments are made for a “he”) is believed to be at least in her fifties, and would therefore be taking a longer imaginative leap than say, Sally Rooney, who is 29. And yet she gets us there, willing us not to scoff at the simmering intensity of Roberto declaiming to Giovanna that, “Life should make you run away when it’s dull,” to which she replies, “Life makes me run away when it’s suffering.”

Somehow, Ferrante finds and asks the question that is at the heart of the adolescent experience, that underscores all the pettiness and the posturing and the bravado and the crippling self-doubt. “I feel ugly, like I’m a bad person,” writes Giovanna, “and yet I’d like to be loved.” Not silly at all.

The Lying Life of Adults by Elena Ferrante is out on 1 September. Pre-order it here.

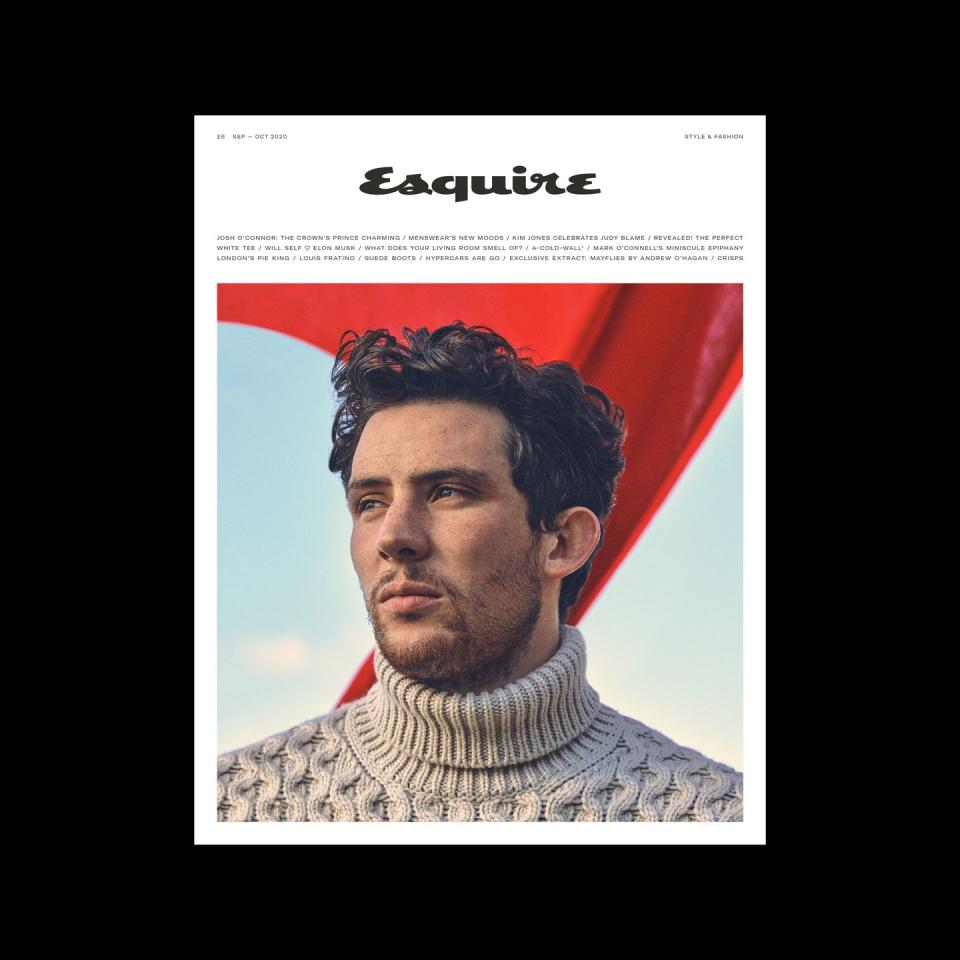

This story is taken from the September/October issue of Esquire, on-sale now.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox

You Might Also Like