How Ellen and Wendy McWilliams-Woods became LGBTQ trailblazers in Akron Public Schools

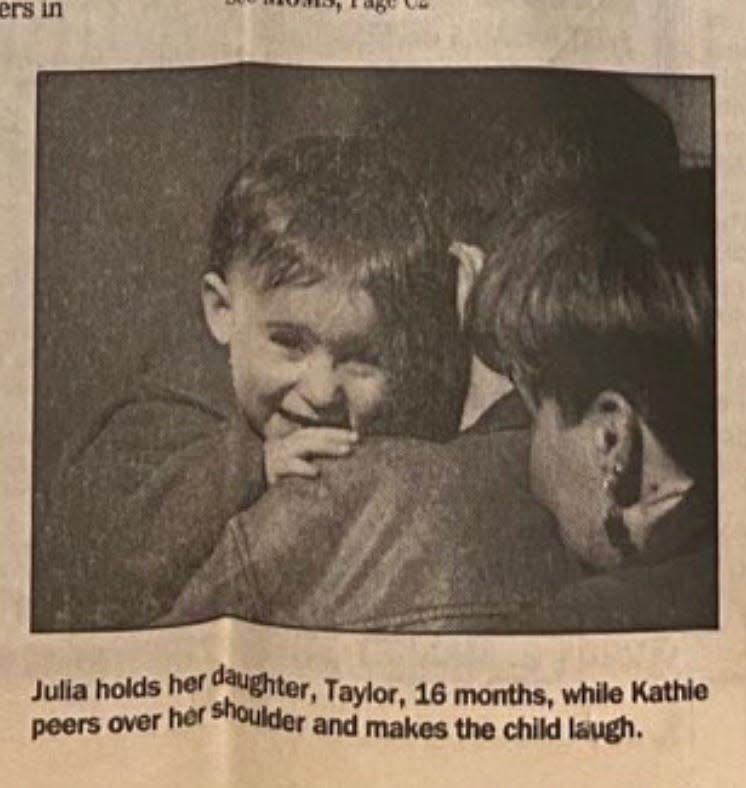

The little girl's face on the front page of the Akron Beacon Journal's Life Style section on March 12, 1997, showed pure joy.

In the black-and-white photo,16-month-old Taylor is laughing as her mom holds her over her shoulder. Her other mother is standing behind them making Taylor laugh.

"Lesbian Mothers," was the headline on the story, which featured two families with lesbian parents, including Taylor's. Her face is the only one visible in the photo, and the caption and the story identify her parents only as Julia and Kathie, noting in the story those weren't their real names.

The two women worked for a local school district, the story explained, and while they were out in their families and at work, they didn't want to cause any "backlash" for their district for employing gay women as teachers.

Those women were Wendy and Ellen McWilliams-Woods, who each had extensive careers in Akron Public Schools.

Thursday, Ellen will retire from Akron as the No. 2 in the district. The assistant superintendent and chief of academics will leave after 30-plus years as a special education teacher and administrator who oversaw massive changes in academics for the district.

She also leaves a legacy of leadership as an out, proud member of the LGBTQ community who, with her wife, pushed the district from the inside for over three decades to be more inclusive to families like hers — just by living their authentic lives.

"Pretty much from the beginning, we never hid who we were," Ellen said at their home in Kent this week.

'We're just going to be who we are'

They met at Kent State University in graduate school for deaf education, where they bonded as political junkies fascinated by the Iran Contra hearings, which were on TV at the time.

Ellen had grown up in a religious family that ran several ministries for people with disabilities, leading her to a career in special education. Wendy started losing her hearing in her early 20s, and by graduate school had learned sign language but still had some hearing function, and switched from a sociology program to one in deaf education.

Ellen had been out since her teenage years and largely accepted in her family. For Wendy, it was a longer journey to understand and accept her sexuality, and Ellen became her first relationship. It was a relief to Wendy to find someone who understood sign language, as she would rely on it more and more until receiving two cochlear implants decades later.

In the late 1980s, Akron schools had one of the largest deaf education programs in the state, so Ellen and Wendy both landed student teaching positions there, and then permanent jobs in the program.

They didn't make any announcements that they were together. But they also agreed they would never lie about it.

"Just from the beginning, we were, like this is us and we're just going to be who we are," said Wendy, who has worked at Kent State since retiring from APS 10 years ago.

Slowly, their coworkers understood they weren't just roommates. Nearly all were accepting, the couple said. They remember Wendy's coworkers calling Ellen when Wendy needed to go to the emergency room after a bee sting, even if she couldn't technically be Wendy's emergency contact.

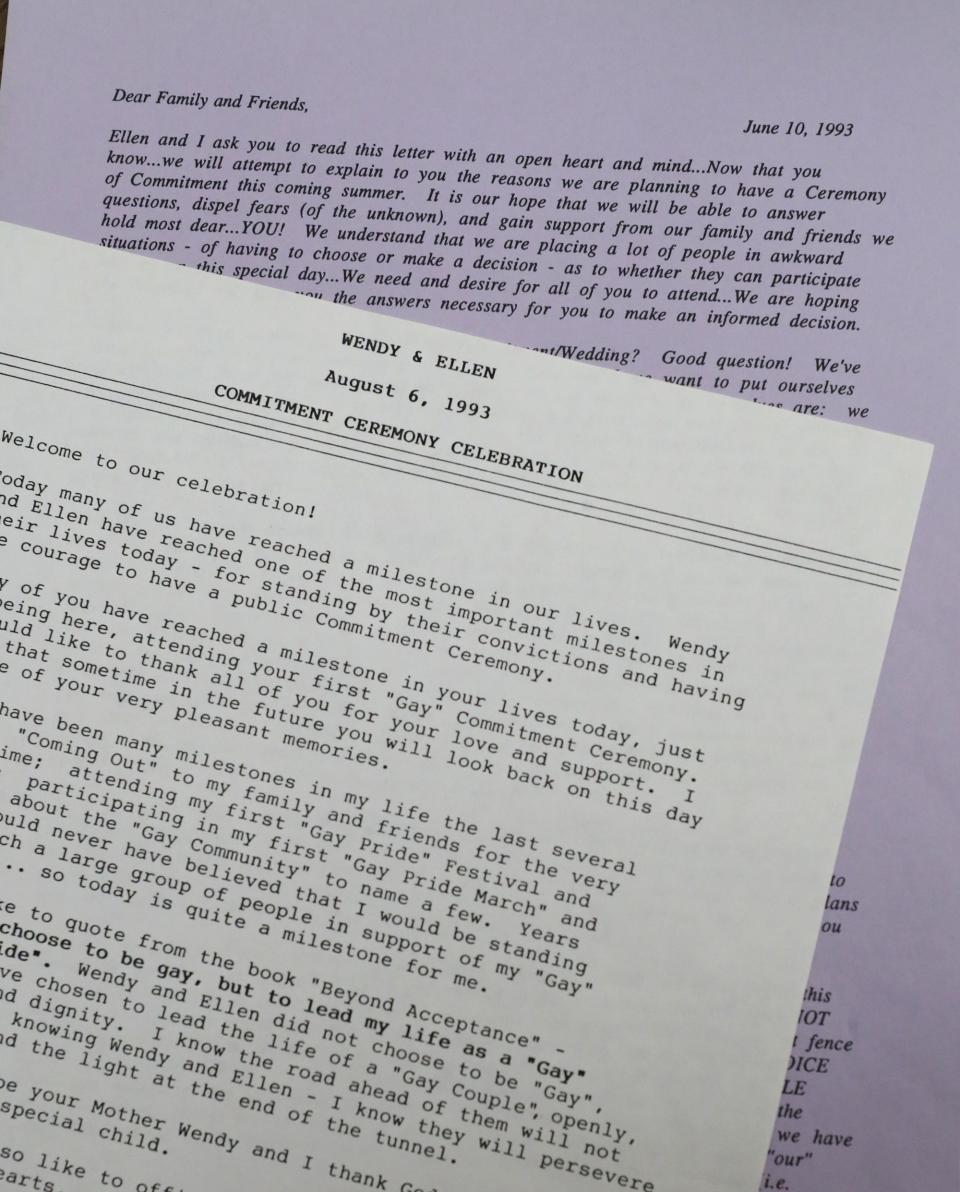

In 1993, the couple wanted to start a family. Being the "progressive traditional" family that they are, they wanted to get married first. That wasn't legally possible at the time, but they wanted to take vows in front of their family, friends and God, just the same as any other couple.

They invited 250 people to a commitment ceremony.

"The minute we decided to do that, this was the moment that, there's no going back at this point," Ellen said. "We're totally going to be out there because everybody and their mother's going to be invited to this."

They discussed the possibility they could be fired, not because of any direct threats or warnings from their bosses, but there were no legal protections for gay employees.

It was worth it, they decided, because committing to each other was something they had to do.

"It was the unknown of what was going to happen, and it felt risky," Ellen said. "And we knew that there potentially could be consequences, there could be consequences for families, it could cause issues for the district. But we also felt confident that we could do this."

Word of their pending nuptials spread quickly. Ellen said they heard from teachers in other school districts that they were the talk of teachers lounges across the region.

"It just wasn't a thing back then," Ellen said. "Or if you did it, it was secretly in your backyard with just 10 of your close friends and that was it. This was very unusual to have 250 people at a big event."

Numerous Akron employees, including administrators, wanted to come to the wedding but were afraid they would be penalized at their jobs, so they called human resources ahead of time to ask permission to attend the wedding, she said.

"Fortunately our human resources office, their response was, 'Hey, it's the 1990s, it's ok, your job is safe, you're not going to get fired by going,'" Ellen said. "But that was the climate and the culture back then, is people were nervous, people were afraid to go."

'People had no idea what to expect' at their wedding

The couple didn't expect everyone to be happy for them. Some expressed they couldn't support the event. Wendy and Ellen said that was OK — they would show grace to anyone who didn't understand, and for close family, would love them toward acceptance.

"We weren't going to be upset about that. We weren't going to reject them because of that," Ellen said. "We knew this was a journey for everyone, and we always felt like we had a responsibility to help people along."

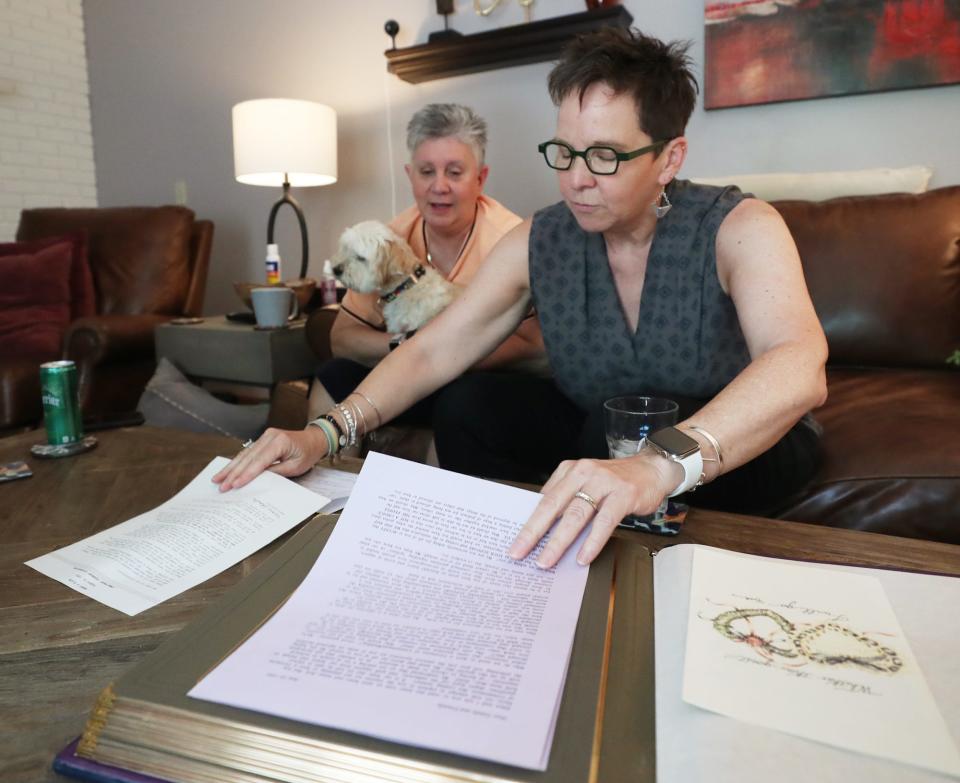

They wrote a letter and sent it to everyone they invited explaining the event would be just like any other wedding they had attended, and their reasons for doing it even though it wouldn't be legally binding.

"We love each other very much... we want no easy way out," it read. "In many ways... we are very traditional."

Ellen said their children read the letter now and can't believe it was necessary.

"Back then, absolutely," Ellen said. "People had no idea what to expect."

Whether out of love or curiosity, nearly all 250 invitees showed up to the Cuyahoga Falls Sheraton hotel for the event.

"They give you an estimate that a third of people invited to a wedding don't come – and everybody came," Wendy said. "So we didn't have enough space for the ceremony. They had to move us out of whatever room it was... They put us literally in the hallway and we ran out and got curtains to cover the (windows looking out to the) parking lot."

The Rev. Joan Campbell, the first ordained woman appointed as general secretary of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S., performed the ceremony. The reception featured an ice sculpture they designed themselves, with a heart and two upside down triangles, a symbol for gay pride.

Wendy's mother, Loretta, gave a speech welcoming Ellen to the family and expressing how proud she was of her daughter and her new spouse for their commitment to each other and their convictions. The speech received a standing ovation led by the 20 or so gay people in the audience.

'I want the same of what any other father gets'

They weren't fired from their jobs. Wendy said the district was "quietly supportive."

But they also were not afforded the same benefits a heterosexual married couple would receive. They had to have their own health insurance plans, increasing their costs significantly. But their first big hurdle was when they had their children.

Wendy gave birth to their daughter Taylor in 1995. Ellen was working in the administration then and was able to take leave she had accumulated to be with her family.

But three years later, when Ellen gave birth to their daughter Bailey, Wendy was a teacher and wasn't sure how to fill out her leave form. She asked another teacher's husband, who also worked in the district, how he took time off when their children were born. He said he marked it down as parental leave, so Wendy did the same.

That's when the call from human resources came. The director, Wendy said, was willing to give her the time off but wanted to know why she couldn't just use sick time.

"I want the same of what any other father gets,'" she responded. "I'm a parent."

She's not sure how the paperwork eventually shook out, but she was satisfied to have stood her ground, and let the district work out the technicalities.

"That was one of those first steps again, just pushing that envelope," she said, noting that largely, they were lucky. "The only backlash we would get were things like that. Just calling and questioning it."

They did receive some questions from their students' parents.

Wendy said one blunt parent, when she noticed Wendy was pregnant, asked her about it and about being a lesbian. Wendy confirmed that she was gay, as she had promised not to lie.

"I said, 'But I'm a good teacher,' and she said, 'Oh, excellent teacher, but God does not agree with (being a) lesbian,'" Wendy recalled. "And I go, 'My God does, but it's ok.'"

Another parent questioned how she would talk to her students about it when she had the baby. Wendy noted her students were kindergarteners and most of them assumed she lived at school.

That parent ended up throwing Wendy a baby shower at the school.

Legal challenges mount in parenthood

Outside of the district, they faced the same restrictions any same-sex couple faced, including not having legal rights to the each other's biological children. Biological mothers had to give up legal rights to allow another person to adopt their children. For example, if Taylor had to go to the hospital for some reason, Ellen could only be the point person on her care if Wendy, who gave birth to Taylor, were not available.

Before the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 in 2015 in the Obergefell v. Hodges case that granted gay married couples the same rights as heterosexual married couples, school districts and colleges were starting to pass their own policies extending benefits for partners.

Ellen said she was a supporter of that in Akron, but didn't want to be the sole flag bearer for the issue.

"This needed to be a district thing that our human resources office or our board had to be advocating collectively," she said. "So I always tried to be careful and tried to inform and advise but encourage to use the normal processes rather than me being the sole person advocating."

The district was working on a partner benefits policy but had not completed it when the Supreme Court ruled, making it moot.

Ellen said Akron schools has always been out front of such issues of equity.

"The district has been incredibly supportive of us through the years and I think they've done the right thing when needed," she said. "I think there always could be quicker movement, but I think overall when you look at the landscape, we have not had the barriers that other people have had."

With that support, she rose to assistant superintendent and chief of academics, appointed to the role 14 years ago by former Superintendent Sylvester Small. Ellen said she couldn't know how many other LGBTQ people are in as high of leadership roles in education in Ohio, but said she didn't know of many. To be at her level now required years of support and acceptance to climb the ladder at a time when that often was not available to gay people, or it came at the expense of living a fully out life.

Wendy and Ellen said that was never an option for them.

Ellen said they always taught their kids to never be ashamed to say "I have two moms."

"And I think that approach is why we've had so much success because there is no shame," she said.

Her work in Akron, she said, and the district's equity work as a whole, has been centered around that same priority of making sure no student has shame for who they are or what their family looks like.

Her own child's first grade teacher was the perfect example for that, she said.

On the first day of school, Taylor drew a picture of her family.

"Aren't you lucky to have two moms!" her teacher responded when she saw it.

Wendy and Ellen sent the teacher flowers the next day.

A ruling and another party for 200 people

When the Supreme Court made same-sex marriage legal, Wendy and Ellen sobbed at the kitchen table. Ellen took the day off in anticipation of the ruling. They made phone calls through their tears, celebrating with their daughters and other family and friends.

They went to the Portage County courthouse immediately to receive an application for a marriage license. The judge briefly sent them away while they worked on language for the application, and when they returned in the afternoon, they received the second application for a license for a same-sex couple in the county.

On their way out of the courthouse, they got a call from Rev. Campbell, who had married them 22 years prior. She was thrilled for them. They asked her to marry them again. She said she would be honored, but she was on her way out of town soon. Could they do it in two days?

Two days later, they held a private ceremony at Campbell's home with just themselves and their children.

"We didn't tell the rest of the family because we knew if we did we were going to have 200 people show up again," Ellen said.

They later threw another party in their backyard for those 200 people.

"I will say our celebration here felt like it wasn't just celebrating our union, we were celebrating the Supreme Court decision as a whole," Ellen said. "We were celebrating the legal part. It was so important for our kids to get that."

This time, no letter of explanation to guests ahead of time was required.

Contact education reporter Jennifer Pignolet at jpignolet@thebeaconjournal.com, at 330-996-3216 or on Twitter @JenPignolet.

This article originally appeared on Akron Beacon Journal: Ellen and Wendy McWilliams-Woods served as LGBTQ trailblazers in APS