Elpidio Valdés creator Juan Padrón was Cuba's Walt Disney. His death brings tributes

Tropical bloodsuckers and a charming liberation soldier, with sun-drenched fangs and valiant machetes, drew part of the indelible legacy of Cuban cartoonist and filmmaker Juan Padrón over a nearly 60-year career.

A pioneer of Latin American animation and a cultural icon in his homeland, Padrón died in Havana on March 24 of respiratory complications (not related to the novel coronavirus) at the age of 73, his son Ian Padrón announced via a mournful Facebook post. Thousands of responses and dozens of video tributes have flooded the family since.

“The last mambí,” as Padrón is often regarded, gave the Cuban people their soul in animated form, creating work with immense pride and clever silliness.

He was born during the pre-revolution era in the Matanzas province on Jan. 29, 1947, and was artistically inclined from an early age. Precociously talented, the 16-year-old Padrón published his first comic strip in 1963.

Around the same time, he began working in animation for state-run television stations. His collaboration with Australian director Harry Reade on the 1963 animated short film “Viva papi!” (which he remade on his own in 1982) and a stint working for the Cuban army’s film department set the foundations for lifelong and colorful audiovisual adventures.

The artist gave birth to his most beloved brainchild, and Cuba’s most emblematic animated character, in 1970 with the first printed appearance of Elpidio Valdés, a mustached mambí fighter in the war of independence between the island and Spain during the late 1800s. A fearless hero, Valdés wittily embodies both a strong sense of patriotism and the “humor criollo” that laughs at local vicissitudes.

Supported by the Cuban film institute, known as ICAIC (Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos), Padrón made numerous “Elpidio Valdés” shorts throughout the 1970s. In 1979, an eponymously titled 70-minute project became the first animated feature ever made in Cuba and to this day one of the most celebrated in the entire region.

Two more movies, “Elpidio Valdés contra dólar y canon” (1983) and “Elpidio Valdés contra el águila y el león” (later re-released as the episodic series “Más se perdió en Cuba”) continued the historically driven franchise. Frank Gonzalez, the voice of Elpidio for all of its existence, would go on to become one of Padrón’s closest artistic partners.

“Elpidio Valdés is a character that reflects Cuba’s desire for independence, the Cuban people’s love for the homeland, and repudiation for interventionism,” Ian Padrón told The Times via video call from Florida in a room decorated with his father’s artwork. “But while my father created it with historical rigor, he also did it with a lot of humor.”

Named after the 19th century Cuban novel “Cecilia Valdés” by Cirilo Villaverde, the round-faced paladin who turns 50 this August has entertained multiple generations of children, and embedded its popular theme song — “The Ballad of Elpidio Valdés,” composed by acclaimed singer-songwriter Silvio Rodriguez — in the collective consciousness.

Animation had featured in ICAIC’s program since its establishment in 1959 with artists like Jesús de Armas and Hernán Henriquez, but before Padrón’s creations, Ian noted, the Cuban animation focused on experimental and highly intellectual productions that didn’t engage with the masses.

“My father’s vision to create popular animation to reach the audience, make them laugh, and pack movie theaters, forever changed the medium in Cuba and influenced other filmmakers to look into comedy and be less didactic in their work,” added Ian Padrón, who considers Elpidio Valdés a brother. (Despite being a fictional entity, the character is as much a part of the Padrón family as any flesh-and-blood member.)

But although Valdés was Padrón’s most endearing character, the animator identified in a stronger manner with his work more imbued with darker hilarity. “My father was never solemn,” explained Ian. “His trademark was his sense of humor, both in his oeuvre and his life.”

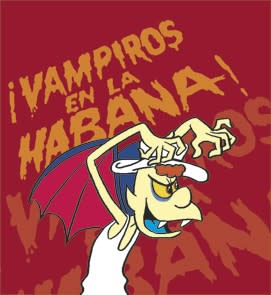

Beginning in 1980, Padrón explored more mature topics in the long-running series of one-minute shorts “Filminutos.” The first episode heralded his interest for placing vampires in a Cuban context, which later evolved into one of his landmark works, the 1985 cult-classic “Vampires in Havana” (available to rent on Amazon Prime), a wacky, 1930s-set, musical period piece that plays with both horror and gangster genre tropes.

Trumpet player Pepito, a descendant of Dracula himself, gets caught up in the crossfire between a Chicago-based vampire gang, Capa Nostra, and European undead posse Grupo Vampiro, as each clan tries to get their hands on the “Vampisol” formula, a potion that allows them to live by day under the sun. For the 2003 sequel “Más vampiros en la Habana,” Padrón brought back Pepito, but this time Nazis enter the picture as new villains.

According to Ian, his father found the fear vampires inspired in people comically paradoxical. He saw them as rather unhappy monsters, unable to enjoy a day at the beach or drink anything besides blood. His “tropicalized” parody pondered what would happen if they had arrived in Havana, where, ironically, the sun burns strongly most of the year.

While “Vampires in Havana,” which was distributed in the United States by the Cinema Guild in 1987, is widely revered, Ian believes that Padrón’s greatest achievement was the “Quinoscopios,” a series of dialogue-free, entirely graphic shorts adapted from drawings by legendary Argentine cartoonist Quino (née Joaquín Salvador Lavado Tejón).

Padrón first met Quino in Havana in the 1980s during the local film festival, where he served as his informal guide. As Ian describes it, it was “amor a primera tinta” (love at first ink). After working on the “Quinoscopios,” Quino allowed Padrón to create a new collection of animated shorts based on “Mafalda,” his most prominent strip, in 1993. The pair remained closed friends over the decades.

Peerless in the history of animation in Cuba, comparable in grandeur only to the U.S.’s Walt Disney and Japan’s Hayao Miyazaki, Padrón operated with scarce resources but vivacious idiosyncrasy that cemented him as a solid influence in the “cubanía” (Cuban identity) and has been a beacon for animators beyond the island nation’s borders.

“As a young CalArts student starving to find Latin American animation, Juan Padrón's fantastic ‘Vampires in Havana’ more than filled my belly with inspiration! To witness such a specifically Cuban film but have it be so incredibly universal was quite the revelation,” said Jorge Gutiérrez, the Golden Globe-nominated Mexican animation director of “The Book of Life.” For Gutiérrez, “the wild story, the hilarious art and design, the incredibly unique animation, the amazing voice cast, and the wonderful music” made the film explode with passion missing in animation from other parts of the world.

During his final years, Padrón dedicated his time, almost exclusively, to painting images of his most famous animated figures on canvases. One of his last public appearances of note was in 2017 when the Havana Film Festival New York hosted an exhibit of his artwork.

He left behind many unrealized projects including a third installment in the “Vampires” saga, a musical based on those same characters, a new book collecting some of his earliest Elpidio Valdés strips, and more screenplays to bring him back to the screen. His last completed painting, a vivid portrait of Elpidio, hangs on a wall in his son’s home.

A filmmaker in his own right whose debut feature, “Habanastation,” was Cuba's submission for the foreign-language film Oscar in 2011, Ian Padrón finds solace in how the memory of his father resonates so powerfully. “He was a very timid person, and he always wondered if people remembered him or knew what he had done. He would be astonished to see how many people from distinct walks of life coincide in their admiration for his work. That would make him very happy.”