Broken Harts, Episode 6: 'Beautiful Black Boys'

Before Jen and Sarah Hart adopted their second set of siblings in 2009, Devonte, Jeremiah, and Sierra had been—according to their Social Security cards—Devonta, Jermiah, and Ciera Davis, three children living in Houston, under the care of their mother, Sherry Hurd, and her boyfriend Nathaniel Davis, whose last name the children took on even before the couple married in 2010. But in 2005 CPS removed the siblings from the Davises' care, due in large part to Hurd's record of substance abuse, and placed them in the Texas foster care system.

When this happened, the children's aunt Priscilla Celestine, the sister of the siblings' birth father, fought to get them out, even moving to a new home and hiring an attorney to help plead her case. Celestine was ultimately successful in having them brought into her care, but not for long; a fateful decision to let the children’s mother watch them while Celestine worked one day resulted in the children's permanent removal from the home—a home the Davis siblings had lived in for only five and a half months.

Celestine tried to fight this decision, but the presiding judge for that case, Patrick Shelton, who is now retired, ruled against her custody. In response to questions about how the Harts were allowed to adopt Devonte, Jeremiah, and Sierra after an allegation of child abuse had already been made against them, he pointed to the lack of criminal charges in the state of Minnesota. Shelton told criminal justice site The Appeal: "Unless there’s a criminal charge, what can you do? Believe it or not, kids get bruises that do not get beat." Shelton also denies reports that he or his associate judge favored nonrelative adoptions over placement with family members.

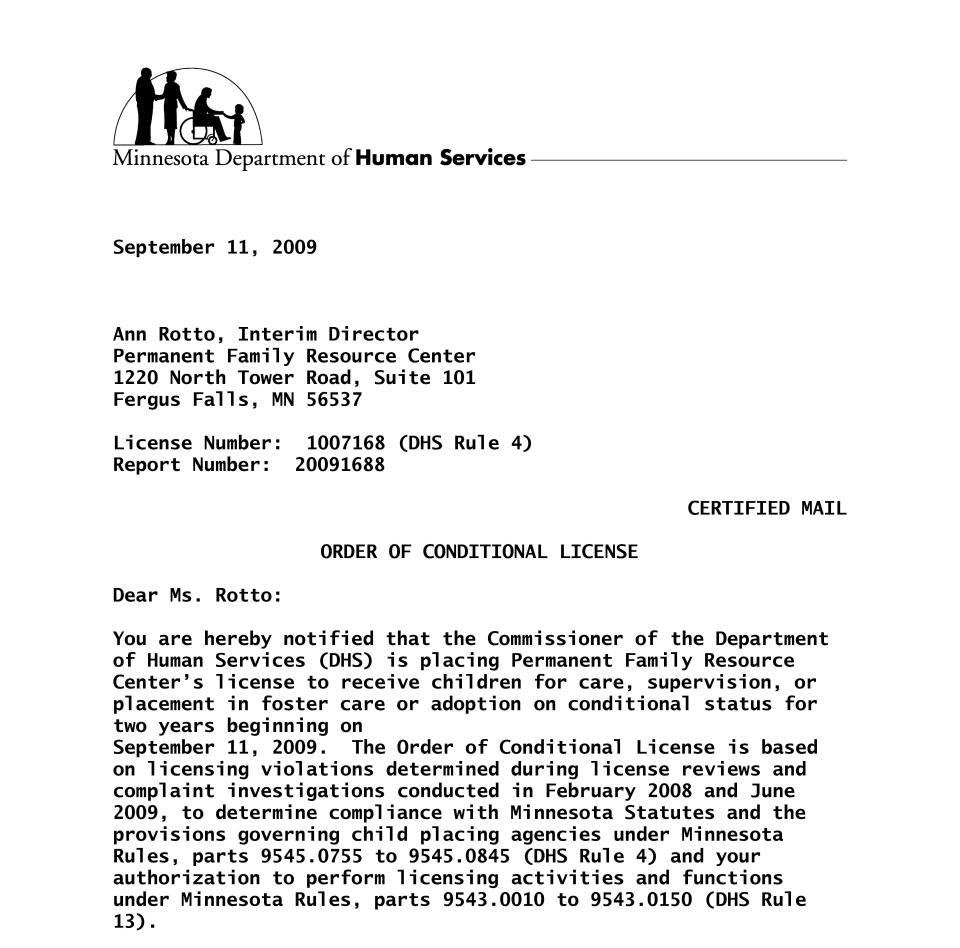

The agency that later facilitated Jen and Sarah's adoption of the Davis siblings closed in 2011, but at the time it was known as the Permanent Family Resource Center. According to a 28-page report filed by the Minnesota Department of Human Services in September 2009, only months after Jen and Sarah officially adopted their second set of siblings through the agency, the organization was placed on conditional status after accruing 17 licensing violations, ranging from failing to submit paperwork to failure to complete proper background checks on participating families. For perspective, over the past 10 years, the Minnesota DHS has issued only three conditional licenses for child placement agencies.

Back when the Harts were clients, the Permanent Family Resource Center ran the Waiting Children Program, a service that provided families in Minnesota and North Dakota with access to foster kids living in Texas, Washington, Ohio, Idaho, Oregon, California, and Florida. The website reads: "Children in this program are living in foster homes or residential facilities and a termination of parental rights (TPR) has occurred. They are legally available for adoption. The average wait for a child after approval of the home assessment is between six months and three years. Individual circumstances and conditions in specific programs may involve a longer waiting period."

It took Jen and Sarah Hart less than a year to legally adopt Devonte, Jeremiah, and Sierra.

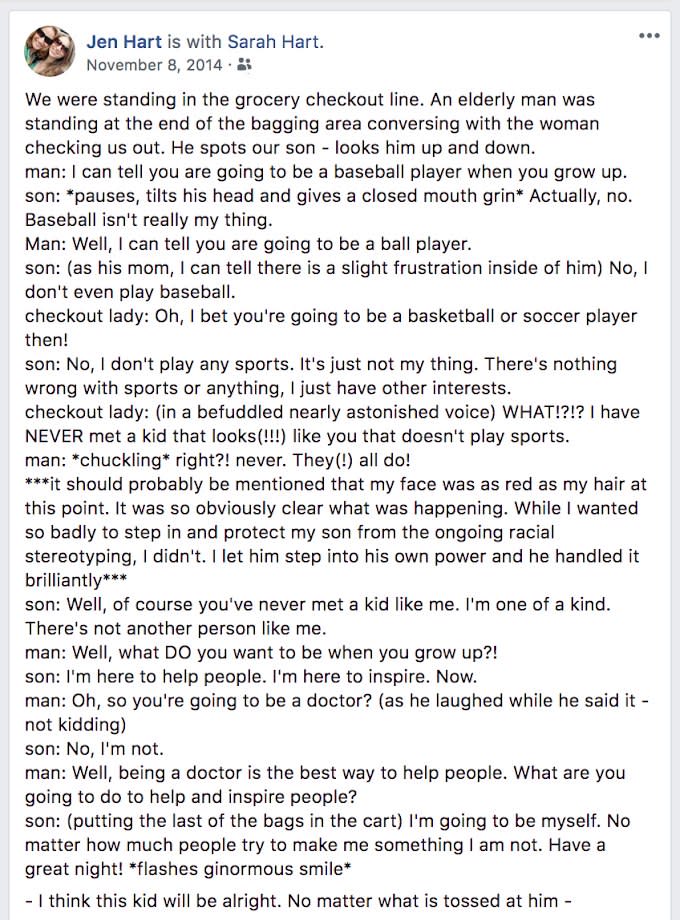

As with many who knew the Harts, Shonda Jones, the attorney who represented Celestine in court, takes issue with the disconnect between the facts that emerged after the fatal March crash and the fiction Jen Hart presented on Facebook. She recalls reading a post wherein Jen describes a particular incident of racism involving a store clerk and Devonte. "I read this article where I think one of the adoptive moms had said she was in a store," Jones says. "She was in a store and she was checking out and a cashier and I think an older gentleman—the impression was that it was an older white gentleman and a cashier who was also Caucasian—were having this discussion about Devonte, asking him something about whether he was gonna play sports."

In the November 2014 post, Jen describes an incident in the checkout line of a grocery store where she says the Caucasian man in front of her takes one look at Devonte and says, "I can tell you are going to be a baseball player when you grow up." According to Jen's post, when Devonte says he's actually not interested in the sport, the Caucasian woman bagging the groceries allegedly replies: "WHAT!?!? I have NEVER met a kid that looks like you that doesn't play sports," to which the man reportedly says: "Right?! Never. They all do." Jen goes on to lament having to watch her child be subjected to what she calls "ongoing racial stereotyping." But Jones doesn't believe the incident ever actually took place. In fact, in her opinion: "It never happened."

Friends of the Harts often recount the stories Jen and Sarah told about how unwelcoming their neighbors were, how much abuse this unconventional family faced, and how “unsafe” it was for them at times. But Bill Groener, who lived next door to the Harts back in West Linn, Oregon, believes that this was a tactical move on the mothers' part. Maintaining a sense of fear may have helped Jen and Sarah keep the ongoing abuse under wraps.

But was this all truly calculated, as Groener suspects? Or was it just ignorance at work? In a July 2016 Facebook post, Jen shares seemingly heartfelt frustrations on the topic of systemic racism. Her words and anguish feel genuine. "My beautiful black boys," she writes alongside a picture of Jeremiah and Devonte smiling in hoodies and beanies. "We talk endlessly about the realities of this world. So much beauty—so much pain and suffering. These boys live and lead with love, but I will never deny them their human right to be frustrated, sad, and ANGRY about the perpetual violence and murder of people of color…. My feed is filled with people (white and POC) that want to help make a difference, but are completely at a loss of what to do. Opening up and breaking the silence is a start, because white silence is black death. If that statement makes you uncomfortable, I'm not sorry. Black pain matters. Black anger matters. BLACK LIVES MATTER."

Back in 2007, after Jen and Sarah adopted Markis, Hannah, and Abigail, a case worker visited the women's home in Minnesota. Her findings were positive—she recommended that Jen and Sarah be allowed to adopt a sibling group of up to five more children. Her report, filed on July 11, 2007, read: "The Harts are open to any race and gender, although they would prefer to have at least one boy in the sibling group. Jen and Sarah have adopted biracial children and they have the tools and knowledge to adopt more children from the African American heritage. They are prepared to advocate for their children and to secure the necessary services to support their family." But what does it mean to be a white advocate for black children?

A 2015 evaluation of data on 600 children adopted in Minnesota, the same state where all six Hart children first lived with Jen and Sarah, examined whether being raised by someone of a different race is inherently damaging. The conclusion: not necessarily. Emma Hamilton, the lead author and a doctoral candidate in counseling psychology at the University of Texas at Austin, put it this way: "Being raised by someone of a different race is not inherently damaging to the development of the adoptees, but that much depends on how white parents talk about race with their children of color and help them identify with people of their own race.”

Jen and Sarah Hart spun alarmingly effective stories, particularly on Facebook, that neatly explained away the kids' strange behavior while simultaneously covering up the truth. They kept Markis, Hannah, Devonte, Abigail, Jeremiah, and Sierra from being able to connect with people who had similar backgrounds. They kept the neighbors from interfering. And most important, they ensured that the voices of the Hart children were never, ever heard. But what was their motive?

That, and more, next time on Broken Harts.

Subscribe now to our new podcast, Broken Harts, from Glamour and HowStuffWorks and based on this story from the October 2018 issue of Glamour. New episodes will air each Tuesday; find them on Apple, Google, Spotify, or wherever you like to get your podcasts. For the full transcript of this episode, click here. Have any tips, feedback, or questions? Email us at brokenhartspodcast@gmail.com

Top photo by Zippy Lomax.