'An embarrassment': Cincinnati borrowed millions to fix roads. They're worse than ever

Eight years ago the city of Cincinnati to much fanfare borrowed $100 million mostly to repair crumbling city streets, but anyone who's driven on city streets lately knows what really happened.

Today, with the money long spent and debt payments rolling in, the city's roads not only aren't in better condition, they're actually slightly worse, according to the city's own road condition index.

In 2015, when Cincinnati City Council approved borrowing the money, the city's roughly 16,000 roads − or 2,900 lane miles− scored 69 out of 100 on the road condition index, a score calculated by the company Data Transfer Services.

The current road condition index is 67, records show – falling short of the 69 minimum rating for the city's definition of "good" condition under its road evaluation system.

In fact, nearly half the city's streets (48%) are ranked as "fair" or worse condition. More than a fifth of the roads: more than 3,400, are graded as "poor" or worse.

The city's top street official told The Enquirer he wished the city could have done more. But paving a mile of road in the city now costs $520,000, up 56% from just two years ago. The city's streets are riddled with utilities or ancient water lines, many of which are also due for replacement, and there's no point in re-paving a street if it will just be dug up for a new water line or cable.

'The city's roads are an embarrassment'

City leaders, including Mayor Aftab Pureval, acknowledge crumbling roads are a problem, but the money to fix them is increasingly scarce.

So now what? In the 2024 city budget, which started July 1, Cincinnati City Council approved spending almost $19 million on street rehabilitation. At a repaving cost of roughly a half million dollars a mile that's 38 lane miles.

And the city will fall behind further every year. City documents show $19 million is far short of the $27.6 million needed for the year's planned projects which means paving and repairs will go undone. Projections show more of the same through 2027, with roughly a $10 million shortfall between the projects needed to be done and the anticipated spending every year.

"The city’s roads are an embarrassment ... unacceptable," said Jerry Newfarmer, former city manager of Cincinnati, San Jose and Fresno and president and CEO of the government-consulting firm Management Partners.

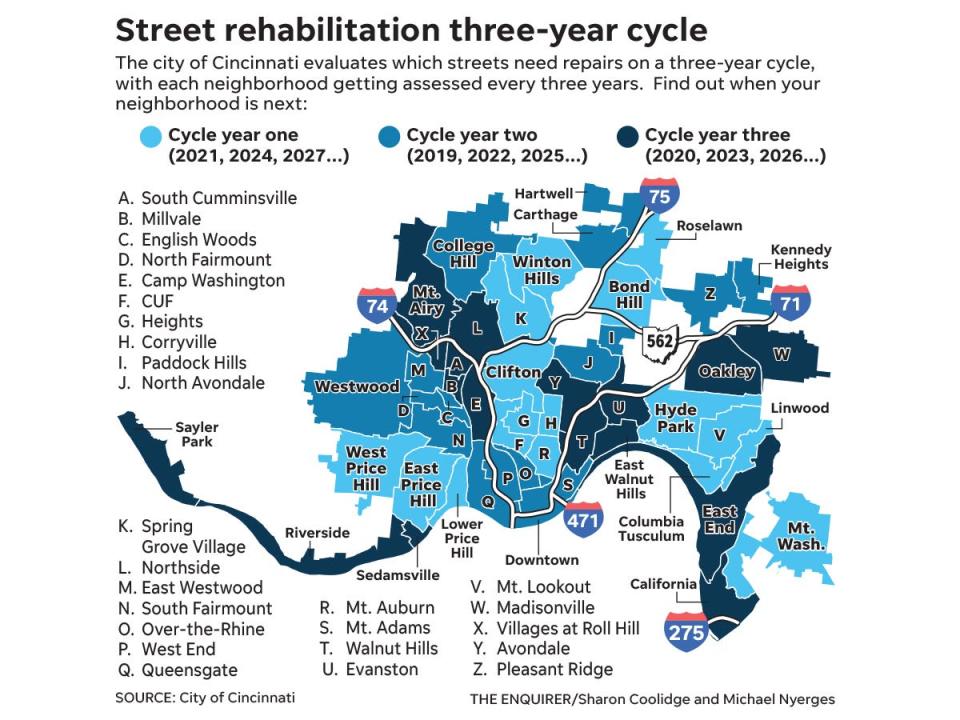

Cincinnati's 52 neighborhoods have roughly 16,065 listed roads the city is responsible for maintaining. Cincinnati City Council in 2000 directed the public services department to repave 100 lane miles per year, something that hasn't happened since 2018.

In 2016, then-Cincinnati City Manager Harry Black rolled out the street plan, pledging $69 million for road repair, with the rest spent on city vehicles. The spending was to last from 2016 to 2021, with at least 100 lane miles paved each year. Data from the city indicates it spent less than $62 million on street fixes.

City records show the 100-lane goal was met in the first three years. In the six years, 520 lane miles were repaved. Another 491 lane miles were resurfaced to help them last longer. But it wasn't enough to even make a dent.

Of the 16,065 roads in the city:

Just 73 − or less than half a percent − garnered a perfect score of 100.

Avondale had 25 of those; Camp Washington, 3; the East End, 1; Madisonville, 10; Mount Adams, 1; Northside, 16; Oakley, 1; Over-the-Rhine, 2; Sayler Park, 1; Sedamsville, 1; South Fairmount, 2; Walnut Hills, 7; and the West End, 3.

On the flip side, 16 neighborhoods had at least 25% of their roads graded "poor," "very poor" or "failed:" College Hill; Columbia Tusculum; East Price Hill; East Walnut Hills; the Villages at Roll Hill; Hyde Park; Kennedy Heights; Lower Price Hill; Madisonville; Millvale; Mount Adams; Mount Washington; Pleasant Ridge; Walnut Hills; West Price Hill; and Westwood.

Chris Ertel, whose official city title is principal engineer, heads the city's street rehabilitation program. But one might better call him the city's "streets czar." He's worked in the department for 24 years. Mention a street and he can rattle off what neighborhood it's in, its pavement condition rating and if it's slated for any sort of fix.

Ertel is grateful for the $100 million council dedicated under a program known around City Hall as the CAP program, short for Capital Acceleration Program. Of that money, $69 million was supposed to be spent on preventative maintenance on top of the annual paving and rehabilitation. Spending data shows $61.5 million was spent on road work. Much of the rest was intended to replace aging police and fire trucks.

The goal is an average pavement condition of 65. His dream? 70.

"It would take so much" to get there, Ertel said.

"The CAP kept us afloat," Ertel said. "We’ve been able to maintain because of CAP. We didn’t make up any ground. To keep it even, it takes $25 million a year. If we want to make an improvement, we need $50 million a year."

Street rehabilitation, Ertel's domain, is big-time fixes. Potholes are filled by another department: Public Services.

What's it like to live and work surrounded by decaying roads?

Herb Kohls, 29, knows a thing or two about poor road conditions: His family's business, Firehouse Nursery in Sedamsville, is surrounded by several roadways in various states of decay.

Located on Sedam Street in Sedamsville, the road in front of the business owned by his dad, is graded "fair." But the busiest streets alongside the property that draw the most traffic are Fairbanks Avenue and River Road – with different segments rated by the city from "good" to "poor." The two other streets that run behind the nursery, Hartman and Delhi are respectively rated "poor" and "fair."

"I feel like every time they fill a pothole around here another one just kind of appears," Kohls said.

While many of the area's streets are an eyesore, Kohls said the community is most concerned about a stretch of Fairbanks, rated "poor," about half a block up from his business that is a busy, curved route that merges into Delhi Pike.

While the speed limit is 35 mph, Kohls notes drivers frequently zip through the area at 50 mph or faster to and from River Road past the Eatondale Apartments. Local children are forced to cross the road to visit the LifeChurch.

"Luckily, nobody's been hit yet," Kohls said, but added a telephone poll there has been struck multiple times.

Ertel, the city's roads czar, said Fairbanks Avenue is one of those city projects that illustrates just how complicated it can get to fix a road. It's not always a question of new asphalt.

The first phase of fixing Fairbanks was the underground utilities: The water main was replaced last year. They knew the area was dangerous, so they had to arrange financing and redesign, which includes a new stop light where Fairbanks curves and meets Delhi Pike. But then Delhi officials said there's a landslide problem near the project site, so city officials had to coordinate it with the township's mitigation efforts.

Construction is set to begin within days, Ertel said.

Nearly half the city's neighborhoods have a bigger share of "poor" or worse roads

At 24%, Sedamsville has a larger share of streets graded "poor" or worse than the city overall. But it's hardly alone: 16 other neighborhoods have at least a quarter of their roads that notch a 50 or less on the city's condition index. Only seven of 52 neighborhoods (California, East Westwood, Over-the-Rhine, Paddock Hills, Pendleton, Queensgate and Spring Grove Village) have fewer than 10% of their roads graded "poor" or worse.

Northside Community Council President Briana Moss said road conditions in Northside, with 17% of roads graded poor or worse, is a top concern and it’s been this way for decades.

She was recently cleaning out a community council storage closet and found a 1981 neighborhood report. The top request to the city? Yep, road repair.

She herself doesn’t drive, but she uses a wheelchair. At times she encountered sidewalks in such poor condition she has been forced into the street, only to find a huge ditch making it more dangerous to use the road.

“A constant thing you hear about is ‘My street is terrible,’” Moss said. “ Potholes. Potholes. Potholes.”

She recently tried to help a citizen get Kentucky Avenue repaired, only to be rebuffed by the city. “The person was being told even though your street is really, really bad, we don’t have any money.”

The city's solution? Have the community council request the repair. That sounds easy, but it isn’t. Community councils every other year can make three project requests to the city, things that typically benefit the whole neighborhood.

“I was super upset,” Moss said. “You expect her to compete with her neighbors for money that should benefit the whole neighborhood?”

Dane Avenue, near the popular Northside Yacht Club, is "genuinely unsafe," Moss said. And it has been that way since she moved to Northside 15 years ago.

“The condition of the streets is the oldest problem in Cincinnati,” Moss said. “As soon as the city started to pull away from inclines and streetcars they created a forever problem.”

Moss said she will continue to vigilantly advocate for her neighbors. But, she added, “I don’t have a great solution other than putting in transit structure."

Northside is slated to be a bus rapid transit route between Downtown and Mount Healthy. More bus use, Moss hopes, would lessen traffic and preserve road quality as much as possible.

It's worse elsewhere in the city.

Nearly half of Millvale's and Mount Adams' roads have ratings of "poor" or worse. Roughly one-third of the roads in East Price Hill, Hyde Park, Madisonville, Walnut Hills and Westwood are also that bad.

City choice: Lower goals or spend more money?

A city audit of the road rehab program, released in March after The Enquirer first sought road conditions, shows the city is so behind on road maintenance there's a $50 million deficit over the next five years just to catch up.

One recommendation in the audit: scale back the 100-lane mile goal. Another says there needs to be a better operating plan.

Officials with the Cincinnati Department of Transportation and Engineering, which oversees the street rehabilitation program, acknowledged problems and suggested a "complete city-wide infrastructure review similar to the Smale Commission from 1987" to determine how much all the needed repairs would cost.

Pureval, who was elected in 2021 and took office in January 2022, said he knows road conditions aren’t where they need to be. The road improvement project was the baby of former City Manager Harry Black, who served under Mayor John Cranley.

“Our Public Service workers and our Department of Transportation and Engineering team do amazing work with the resources available, but the reality is clear – our roads need more repair,” Pureval said.

The city has $400 million in deferred maintenance issues, which includes sidewalk and road repairs. “Costs are rising more quickly than revenues.”

He cited the possible sale of the Cincinnati-owned railroad this November, which is subject to voter approval, as part of the solution. The plan is to sell the Cincinnati Southern Railway to Norfolk Southern for $1.6 billion. That money would then be used to create a trust and investment money from the trust would be directed toward current city infrastructure. It's anticipated to be an amount that's at least double the $25 million the city gets from the railroad lease, money that is also used on infrastructure.

“I added an additional $2 million in this year’s budget toward street rehab, but we need to do far more,” Pureval said. Council had been slated to put $17 million toward road maintenance, but Pureval sought the higher amount.

Councilwoman Meeka Owens, chairwoman of Council's Climate, Environment and Infrastructure Committee, said she knows the poor condition of city streets are on residents’ minds.

There will never be enough money for the city to repair streets in a way that's acceptable, she said.

“It’s a looming issue,” Owens said.

She echoed Pureval in saying money from the railroad sale could help with street repairs and repaving but said it’s time to do things in a different way.

“We need to think about bike lanes, multimodal transportation, Red Bike, scooters. How do we hyper-elevate those modes of transportation? There has to be a transformational shift in how we think about transportation.”

Still, Newfarmer, the former city manager turned consultant, said ensuring residents have driveable roads is a basic necessity for the city.

“Scaling it back is going the wrong way," Newfarmer said. “Taking care of the roads and other infrastructure is the second most important thing the city does. The first thing is public safety ... leaders of the city are stewards of the condition of the infrastructure."

Newfarmer is a city resident and sounds like one.

“I have not driven on all the roads of the city,” he said. “The ones I have driven on are in pretty bad shape.”

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Why are Cincinnati's roads so bad? $100 million later, they're worse