Emerging voice in poetry Courtney Faye Taylor is helping us 'Concentrate'

I like to think I have an ear for stars in the making, like I can see those atoms of light circling each other, ready for gravity to squeeze them together and create something dazzling. After all, I was bopping to Lizzo when she was just a Big Grrrl in a small world (somebody please tell her to put that album back on Spotify) and forcing all my friends to listen to her too.

When it comes to my interests, especially music and art, I do the opposite of gatekeep. And so you, my dear reader, absolutely need to hear about this up and coming writer I’ve encountered. She’s a real classic in the making.

Poet, artist, Cave Canem prize winner, and 2023 NAACP Image award finalist Courtney Faye Taylor will be visiting Savannah State University (SSU) at 1 p.m. and the Book Lady at 7 p.m. on Friday, Feb. 10 as a guest of the Georgia Poetry Circuit (GPC). SSU has been the first and only HBCU part of the GPC since 2014.

More:Designer Natalie Chanin weaves creativity and community in her latest book, 'Embroidery'

More:Unvarnished Theater re-emerges in Savannah with staged reading of 'The Moors'

More:If you run across a severed limb in Savannah, don't freak — it's just art

In partnership with the Book Lady, the university has been able to bring three poets a year to visit and talk with its students, although it’s a task that’s become more and more difficult over the years. “Because the university has had some massive budget cuts, we can no longer use state funds,” explains Chad Faries, professor of creative writing and literature and SSU GPC liaison. “We're trying to fund it hopefully either through our student group, or seeing if we can get a donor to ensure that the circuit continues.”

Despite Faries’s admitted bias (he’s also a poet), he believes poetry can convey a more impactful message on current issues than hard news articles. “As an educator, I'm interested in critical thinking,” he says. “But as a poet, I'm also really interested in affairs of the heart, what moves us and what motivates us as humans.”

This ability to touch people’s hearts is exactly what he saw in Taylor’s work when she was nominated as a GPC poet. “She's a good fit for Savannah State, I would say, because she's exploring very specifically the Black female experience,” says Faries. “I feel like she has messages that need to be heard.”

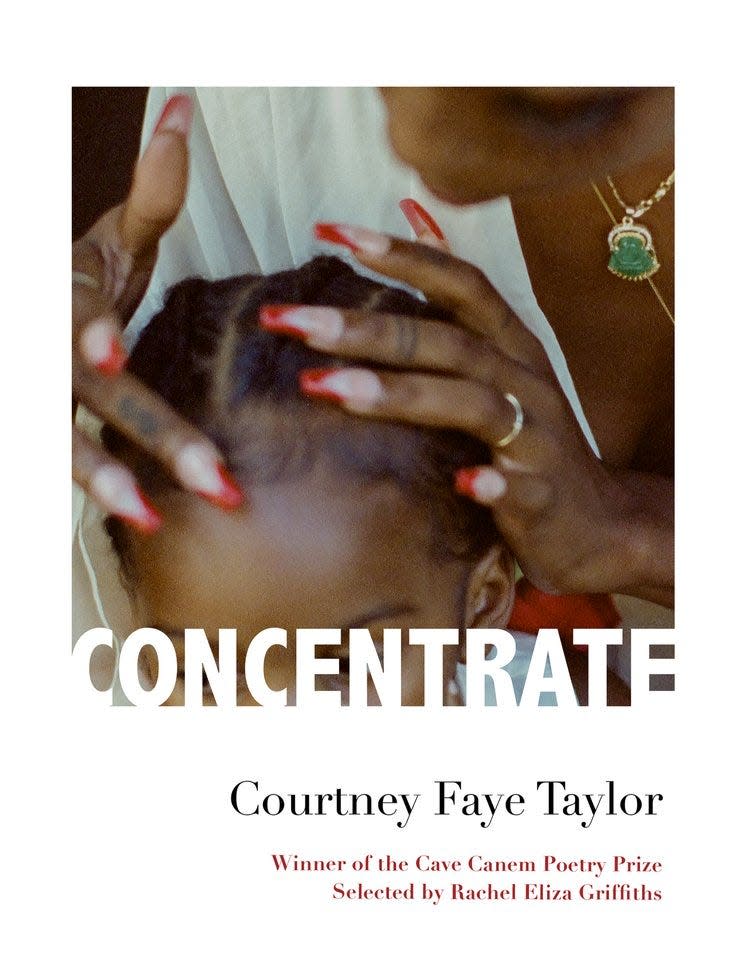

Along with those messages, Taylor brings a tenderness to activism that reminds me of classic practitioners such as bell hooks and contemporaries such as adrienne marie brown. Her debut collection "Concentrate" is an exercise in defining care as “empathetic intention” rather than a well-meaning but ultimately empty platitude.

There’s no shortage of Black tragedy but the result is those tragedies blending together and one becoming numb from experiencing it so often. It can end up a double-homicide of sorts — the first, a physical death; the second, metaphysical, a reduction of a full, complex person to a cautionary tale.

The 912: Rest in Power, Tyre

One such story caught Taylor’s attention. In 1991, Latasha Harlins, a 15-year-old Black girl, walked into a convenience store to buy orange juice and was subsequently shot and murdered after being accused of shoplifting by the Korean American shopkeeper Soon Ja Du. This incident and trial, which resulted in no prison time for Du, led to the 1992 LA riots. Unfortunately, this story is neither new nor unique. Harlins is another scarlet stripe on this country’s flag, her second death the erasure of her as a Black girl who lived 15 full, colorfully complex years of life before she was shot.

Taylor performs careful and reverent necromancy in reviving the rest of Harlins’s story, examining this in the context of Black girlhood, tension between communities of color and white supremacy’s role in that. She dissects these topics with the meticulousness of a surgeon yet the understanding that these things can be messy and contradictory and aggravating. “I'm [still] going to write about that pain, if writing about that pain frees me or someone else,” Taylor says. “I think it's important to center myself and my communities, to not write to be understood or digested by whiteness, to not translate my experience so that it's simplified for whiteness.”

After remembering Alexis Patterson, a Black girl who had gone missing when Taylor was young and growing up around Milwaukee, she searched the internet, wondering if she’d ever been found. Though that search initially had nothing to do with her debut collection, it sparked a curiosity to excavate the representation of Black women on missing person fliers. “A lot of things come from curiosity,” Taylor says. “I'd say I'm curious about something and so then I walk into it.”

Often, the urgency of the internet can push us into the “Why is no one talking about this?” frenzy, especially when it comes to instances of Black tragedy. However, Taylor defies that urgency, prioritizing handling the story and herself with care, leaning on the idea that “rest is resistance.”

More:Why an Oscar-nominated actor is coming to Savannah to perform in the former Calhoun Square

Inspired by collage artists Debra Roberts and Lorna Simpson, vocal and visual poet Douglas Kearney, and contemporary painter Rozeal, Taylor compiled her research on Harlins’s story with posters of missing Black girls and women. She conducts this exploration of Blackness, femininity, and coming of age against the backdrop of white America and the tensions and unity between communities of color through a range of forms — from poetry to essays, collages to plays.

“I think even experimenting with form in Concentrate was a way for me to give myself reprieve because there's something about allowing myself to process traumatic events through multiple mediums that gives a sort of breathing space,” Taylor explains.

It’s important to note, though, that this doesn’t mean she avoids feeling the full weight of the heavy subject matter. “I also think painful work is painful work,” she says. “There's a little bit of it where I need to feel those things in order to work my way through it; it's like a balancing act.”

After reading her work and other interviews, it was in speaking with Taylor when I could clearly see the grace with which she performs that balancing act. There is a tender and heartfelt yet grounded and firm nature to her voice. I heard both layered echoes of "Greats" from the past and the warm familiarity and chic cool of an older sister.

It’s a voice that will no doubt carve its own echo in poetic history, a voice that will become a star and hang in the sky for years to come. For now, I’m grateful that voice will fill the intimate space of our local bookstore here in Savannah.

In Conversation with Courtney Faye Taylor

So you’re about to visit several universities across the North and South, is there anything in particular you’re most looking forward to, whether that’s in the author talks or within the cities themselves?

"When I wrote 'Concentrate,' I really hoped the book would spark meaningful conversation. So, when I'm on the Georgia Poetry Circuit, I'm looking forward to engaging in those important conversations with readers. I want to hear the different ways people enter the material of the book and the different ways people come to understand its navigations of white supremacy and racial opposition, and how readers bring their own lived experience to that understanding.

"I approach a lot of my events as this kind of blend between a reading and a craft talk. So I think that really invites a certain level of engagement that opens up space for that kind of dialogue. So I'm excited for that. I went to undergrad at Agnes Scott College in Atlanta. When I was there, I spent a lot of time in Atlanta, never really went to other parts of Georgia, so I'm also excited to just see Georgia. I feel like I won't have any other opportunity to see all of these cities. It's exciting to get to know the state in that way."

Place plays a significant role in 'Concentrate.' Is there a way that you plan on capturing your travels for future work? Where do you typically look to find the heart of a place you’re visiting (book stores, coffee shops, beauty supply stores, etc.)?

"I love this question. Because yeah, I think, really, for me, when I think of my favorite part of Concentrate, or the part that was the most pivotal for the collection, was going to LA and writing those essays that appear in 'Four Memorials.' That trip did make me think of ways travel could play a part in my writing as a whole. I'm somewhat of a homebody, so traveling consistently is like a new thing for me. And it's particularly new because I'm on tour. But I've really enjoyed it so far.

"And I do think there's a way travel can show up in my work again, partially because I think I'm a different writer in every different city that I've lived in. I think there's a poem that I'm writing, let's say in Kansas City that I would never write if I was living in Atlanta. So I do think wherever I move my writing kind of moves. And yeah, I would love to see how I can kind of lean more into place in my work in a very deliberate way."

Are there places that you tend to visit when traveling that you're like, ‘oh, I have to go to that city's local coffee shop or restaurant or something’?

"I'm big on coffee. So everywhere I go I have to find coffee shops, several coffee shops. So yeah, that is important. I think it also depends on where I'm going. I just came back from DC and so I was like, ‘every time I'm in DC, I gotta go to the Black Smithsonian now.’ I think going to historical sites, Black-owned bookstores, coffee shops is always important to hit on when I go out. "

Since you’re a homebody, how do you take care of yourself while traveling? And because a good bit of 'Concentrate' centers around racial and sexual violence, were there ways in which you practiced self-care so you didn’t harm yourself in the process of engaging with difficult subject matter?

"Yeah, while traveling, self care just in general, I take my time. I also think that's true of my writing. I take my time while writing not to rush my emotional process, taking breaks. I also [believe] that “rest is resistance” idea, not letting this fear that I'm on a time limit affect the work that I'm doing. I think even experimenting with form in 'Concentrate' was a way for me to give myself reprieve because there's something about allowing myself to process traumatic events through multiple mediums that gives a sort of breathing space. So I'm processing all of these events and ideas through poetry, essay, visual art, playwriting in some instances, and I think all of those genres helped me move through the work in different ways that I needed at different times.

"And then in the same vein, I also think painful work is painful work. And so there's a little bit of it where I need to feel those things in order to work my way through it. So it's like a balancing act between ‘I need to go here and I need to let myself go here’ so that I can capture what I'm trying to say. But yeah, I think overall having those practices that we can turn to when we do need that space and that joy redelivered to us is really important."

In that same vein, do you feel there’s this extra pressure on Black artists, sometimes even more so on Black women artists, to constantly be engaging with and making art about tragedy in order for their work to have value? Is there any advice you have to free oneself from this pressure?

"Yeah, this is a good question. Because I do think whiteness expects us to perform our pain and industries make money off of the backs of that expression. So I'm always mindful of the ways work about Black pain is digested, but at the same time, I'm [still] going to write about that pain, if writing about that pain frees me or someone else. So when I do that sort of work, I think it's important to center myself and my communities, to not write to be understood or digested by whiteness, to not translate my experience so that it's simplified for whiteness.

"I think that's the advice I would give to Black writers, to stay true to your voice, to read other Black writers who do this work, and just establish community with those writers. I think we often think of writing as a solitary act, but it's heavily communal and so leaning on other writers who write about our multifaceted realities and how they navigate what that means to do that work as a writer, and how that impacts itself but also what it means to put that work out into the world and not have control of how it is taken, and how it's dealt with. And with that in mind, just making sure that we put that work out with immense care."

Are poems typically arriving to you like that as images and stories that you're encountering?

"Yeah, I think that I'm kind of one of those poets that tends to wait for inspiration to strike. I kind of have to be moved to write something. Though I do sit down almost every day to write, most of that writing is revision, but the initial part of a piece is usually like an uncontrolled spiritual sort of thing. It's like a line that will come to me, a certain scene, and then from there, the work evolves and grows over time.

"But recently I've been more driven by feelings. A certain emotion will spark a session of writing. I think after that spark, after I've let everything out, I have this long word document of writing or if I'm working with images, I'll have all these images, which I'll think of as like an ice block, and then the revision process is like chiseling it away to create that sculpture.

"For 'Concentrate,' it’s interesting to think about how certain poems came to be. Like you mentioned, the missing flyers. How that kind of came was that I just randomly remembered a Black girl who was missing when I was a child. When I lived in Wisconsin, I lived near Milwaukee, and her name was Alexis Patterson. And she’s still missing. I just remembered her one day and I was like, ‘I wonder if anyone found her.’ I was just Googling her and then I found the missing persons flier for her and then I kind of started to look at other missing Black women and girls.

"So it came from that; it really had no link to 'Concentrate.' And so, from there, I started becoming interested in the way Black women and girls were defined on these fliers, the images that were used. And just examining that medium, like that missing persons flier, and what it means. And so from there, the visual poem came and then from there, I saw how it could fit within the larger concept of Black girlhood that I was talking about in my book. A lot of things come from curiosity. I'd say I'm curious about something and so then I walk into it. And then other times, it's a line or an image that I write down in my iPhone Notes app and then somehow it finds its way into a larger work."

What does your editing process look like? How do you refine expansive, sometimes amorphous subjects into one centered piece of topical meditation?

"Yeah, yeah, that's hard to kind of think about the ways that we sink down to focus on one thing. I think that was a big thing I had to deal with while editing this book. It was an exciting but a very rigorous process. The draft of the book that I brought to the publisher is much different than the one that's out in the world right now. And this was my first time working with professional editors, so I was really grateful for the perspective they offered and the ways they would see my work because they were completely new to it.

"Editing involved a lot of organizational changes. I don't have a lot of titles for poems in the book and so when they got the book, I wanted it to feel like a collage and poems run into each other because they're not defined by having separate titles, but it did make for a confusing reading experience. So, we worked to put in more section breaks to instill a clear movement and progression through the book. Editing was also a fair amount of cutting, letting go of poems I loved but poems that didn't quite fit the message I was trying to deliver. I think the silver lining of that is that those poems still exist and they have life elsewhere, they will have life elsewhere. It's exciting to see them reborn in another context."

It’s like arranging a gallery, right?

"I love that. I love thinking about it like a gallery, and it's hard because there's no right answer to what sits next to what but it creates really different stories. So when you're working on something where there are like so many stories you want to tell, it's hard because placement determines that story to some extent. And then the book really lives in that format forever. A lot of poets work in more digital forms where they can manipulate maybe a poem in the book over time. So there is a space that we're in where we're thinking about how to allow poetry to live even more so, how it can live in the digital space. So I think it's an interesting conversation that's still happening."

In your discussion for Poets & Writers, you mention making sure your work is in “caring hands.” What led you to Graywolf press and how were you sure that was the right home for your manuscript?

"Yeah, I've always admired the poets that Graywolf publishes. Claudia Rankine's book 'Citizen' was one of the first texts that I read when I was getting my MFA. It had a big impact on what I imagined for myself as a poet. Harriet Mullen, another Graywolf poet, was another early influence of mine. I tried to find presses, magazines, organizations that have a good track record with supporting and honoring their artists. Graywolf was one of several I think did a really good job with that. My experience with them only confirmed that and it's been really amazing. But to some extent, I mean, it's still a risk wherever you go, because you will never be able to know how your experience will be unless you just kind of lean in. But to me, it's important to look at the writers whose books have shaped me and see who those writers have trusted with their work."

Today, there seems to be a harsher magnifying glass on words and their role in perpetuating certain cultural stereotypes. However, sometimes that magnifying glass can be so harsh and unforgiving that there’s no room left for nuance in the race for political correctness. In your interview with the Poetry Foundation, you mentioned your hesitation with including racially insensitive terms from Ice Cube’s 'Black Korea.' It also made me think of the more recent use of a gay slur in Kendrick Lamar’s 'Auntie Diaries' that ignited online debate on what constitutes purposeful use of stereotypical slurs in art. What would you say is the line between purposeful and gratuitous?

"Yeah, that poem was one that required me to really think about what I wanted to say and the impact of what it would say. At first, I had taken those words out and what remained in their place were these open brackets to suggest that something had been taken out, so using erasure to make a commentary. But once I spoke with my editors about that poem, we kind of talked about what that removal does and the ways that it can kind of sanitize the history. And so it became important for me to include those words, because I wanted to make sure I was accurately representing the tensions and hostilities that defined that period. So, to me, it started to become like I want to be truthful, even in the ways where that truth feels so uncomfortable to point to. Especially because I'm pointing to this example of anti-Asianness that is perpetuated by a Black artist. It feels important to point to that too, just as [important as] pointing to anti-blackness.

"So it became an important thing to keep. To remove the lyrics from the song would be running the risk of sanitizing that and not shining a light on that. And so in 'Concentrate,' it was important for me to show the entirety of our dynamics as communities. What I hope to do through reusing Ice Cube’s lyrics is to create a new conversation about the song, hoping to allow us to think of it in new ways, and to consider it critically against the backdrop of the LA uprising and the insidiousness of white supremacy that pits communities of color against one another.

"I think ethics are always at play when we write about marginalized communities, especially ones outside of our own lived experience so there's always a consideration of what's purposeful versus gratuitous. My guiding light, in writing 'Concentrate' and all my work, is care. I want to make sure whatever I'm doing, is done first and foremost, with empathetic intention. And so I do think that was kind of a central obsession of mine: the care in everything that I was doing."

This is the nuance missing from online conversations.

"In Kendrick’s case, he's creating a whole new song, choosing to use that slur there, which I think calls into question ethics in a different way. I just feel like there's a lot of nuance to the choices we make as artists and we never escape responsibility either. I think that accountability is also really important."

I love that you love reality TV, especially since it’s often dismissed as 'junk food' or a 'guilty pleasure.' And despite its name, it tends to present this caricature of people that feels furthest from truth. Still, as the saying goes, art imitates life, so I’m curious to hear what artistic inspirations you find in reality TV when your poetry leans toward a grittier, more grounded tone and structure?

"Yeah, I love reality TV because it is so unreal. It is more unreal than any fictionalized or scripted movie or TV show, but it's marketed as authentic so we subconsciously feel like we're getting this dramatic inside look into someone's really messy life. And I get invested in it, like I really do care what happens on 'Real Housewives' and I really do care about the couples on 'Married at First Sight.' It's escapism.

"In that same way, doing writing exercises while I'm watching these shows feels like a fun escape from the serious nature of what my writing can be. And I really love to see what becomes of these poems that are like these little transcriptions. They read like a collage of voices and they remind me of some of the poly vocal work that's done by poets like Fred Moten and Harriet Mullen. I think I'm still trying to figure out what reality TV has to say about me, but I feel like there is something about our interests and obsessions that have something larger to say. I think what it's teaching me is to pay attention to what I'm drawn to and why there is more to say about that. As I figure that out, I'm excited to see what comes up."

There is this addictive quality to it and it is entertaining.

"I don't know if you watch the Circle. I think when it first came out, I was just so interested in it being a game show where manipulation is the point. Social media is a manipulation. But we kind of pretend like it isn't. This social environment is created very intentionally for me to maneuver in a certain way. In a very fun, light-hearted way, [it] points to the inauthentic nature of what we do every day when we get on the internet. So that's another one that's just really interesting to me."

Your collage work reminds me of the visual artist John Alleyne’s silkscreen monotype print “In Between the Skin Fade” and Glenn Ligon’s "Runaways "(1993). Were there any specific artists that influenced or guided your visual practice while working on Concentrate?

"Debra Roberts and Lorna Simpson are two black collage artists that really inspired the way I approached collage in 'Concentrate.' In the book, I write about the visual art of Rosario, particularly their woodblock prints that merge Black and Japanese culture. I write about that in a direct way. That work was really influential to me and I came across it in the middle of writing the book. I went to 30 Americans, which was this exhibit that was touring around like some years ago. I also think of poet Douglas Kearney. He does a lot of sound and visual work in poetry. And so that's another influence of mine, particularly him influencing the ways I saw writing’s potential to lift off the page. I think of those as the influences, and there are many, but those come to mind."

Like you mentioned before, being a writer can be isolating work. How do you seek community when you need to take a break from the page?

"I have some friends that I exchange work with here and there. It's important for me to have people I can call on that are my go-to readers. That became even more important after I left academic spaces. I wasn't in undergrad anymore, wasn't in the MFA, so I didn't have a built-in readership anymore and kind of felt like for the first time, I was out here alone without real readers that I could go to any time. It does take time to cultivate that community, so I'm happy with the ways that I've cultivated that and the ways it's still growing.

"An organization that's been key to that is Cave Canem, who gave me the prize but also has the yearly retreat. It was the most meaningful workshop. I feel like I would bring in these poems and my workshop group would be like ‘it’s not there,’ but they were meaning it in a way like ‘you’re not present in this work’ like ‘I’m not feeling this work,’ very much in the way of ‘you have more to say; there’s a truth that is right there but it’s just not on the page yet.’ And no other workshop has been able to really get at that for me as a Black writer. It’s invaluable to have someone who can see you so quickly, like we don’t know each other but you can see me so quickly because you share my experience and you care about my experience in a way that no one else really can."

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: Courtney Faye Taylor on her new book 'Concentrate' at The Book Lady