Empty cockpits, canceled flights, crowded airports: Congress tackles pilot shortage

AJ Sick sat in the Denver airport for 11 hours.

The 27-year-old from the Chicago suburbs was stranded on a June afternoon after traveling to Colorado for a wedding. His flight was scheduled to leave on a Sunday at 3 p.m. but kept getting delayed − not from bad weather but because of a missing flight crew.

A gate agent announced later that evening that the flight was rescheduled for the next day.

Sick said the line for customer service stretched for more than three gates. He thought about renting a car to drive 12 hours home. None was available. He contemplated purchasing a car to drive home and resell later at the used car dealership where he works, but the news of the delayed flight came too late.

“We were clueless. We were misinformed in the beginning,” Sick said. “They assumed the flight crew was going to be on, but they all timed out.”

Sick is just one traveler who has experienced turmoil at airports this summer as the airline industry grapples with several problems leading to flight delays and cancellations:

Pandemic-era staffing reductions.

Bad weather that exacerbates staffing shortages.

A pilot shortage with nearly 15,000 pilots set to retire in the next five years, according to a 2022 study from the Regional Airline Association.

Air traffic controller shortage with 10% fewer fully certified air traffic controllers than a decade ago.

Increased demand as pre-pandemic travel levels return.

Lack of resources and support for prospective pilots.

These are problems that lawmakers in Congress are working to address as the two chambers debate the Federal Aviation Administration reauthorization, legislation that authorizes funding for the agency through fiscal year 2028.

Specifically when it comes to a shortage of pilots, those leaving the field exceed those entering it. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 18,000 openings for airline and commercial pilots are projected each year.

Dennis Tajer, spokesman for the Allied Pilots Association, the labor union representing American Airlines pilots, said addressing the shortage is a pipeline problem that starts in the cradle and ends in the cockpit.

“There’s pilots out there; they’re just not getting through the pipeline quick enough,” he said.

More: FAA warns staffing shortage could snarl summer travel

A childhood dream

Ezekiel Andrews’ first flight was at 12 years old. His family was traveling from Birmingham, Alabama, to Columbus, Ohio. Andrews' grandfather, who had a fear of flying, opted to travel by bus.

The then-12 year old embarked on a Southwest plane, and when the plane arrived in Columbus, his grandfather was still an hour away.

“It was from that moment on,” Andrews, 37, told USA TODAY. His curiosity for how he arrived home faster than his grandfather led to his childhood dream: becoming a pilot.

Andrews graduated high school, assuming he needed to join the military or earn an engineering degree to become a pilot. He decided to enroll at Auburn University to study engineering.

His ongoing 10-year journey to becoming a pilot hasn’t been easy.

Two years into his program at Auburn, Andrews pivoted from engineering to enroll in the aviation program at the university and started taking flight lessons. But he struggled to pay for the flight hours required to advance his certifications, working multiple jobs in factories and warehouses to make ends meet. He paid $170 an hour for a plane rental and instructor. Now, he estimates those prices have more than doubled.

“I’m just broken, like a broken car on the side of the road just watching everybody driving by because I just couldn’t afford to get the repair person out,” he said.

He was told several times he needed to drop out, but his dedication never faded. He saved enough money to buy a flight simulator and used his college girlfriend's laptop to practice flying. For Andrews, it wasn't about lack of skills but a lack of resources.

It took him one year to reach his first solo flight, when it typically takes a few weeks to a month, he said.

The path to commercial airlines

Aspiring pilots start as student pilots before advancing to become a recreational pilot. They then reach the private-pilot level, when they can carry passengers and fly for limited business purposes, before moving on to obtain a commercial rating, which allows them to fly for hire and compensation.

The Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association found 60% of those who earn a student pilot certificate never progress in earning additional licenses. Seventy percent to 80% drop out before obtaining a student pilot certificate.

The final license – an airline transport pilot certificate— allows pilots to fly with major airlines. The FAA in 2013 raised the minimum requirements for the certificate to 1,500 hours from 250.

Most pilots, like Andrews, work as flight instructors to obtain more hours. He has earned 530 out of the 1,500 hours needed.

The pay is poor − Andrews makes $10 an hour for office work and $20 an hour for flight instruction. Because of bad weather or malfunctioning equipment, he often doesn't spend a full eight hours in the sky. He hasn't been able to keep up with his peers who are now flying 737s with major airlines while he is still working to rack up flight hours.

Andrews struggles to support his family and 2-year-old daughter. Plus, he owes a lot in loans− more than $120,000 for his four-year aviation degree and an additional $120,000 for his pilot certifications.

“If I lose my job, it’s going to be almost impossible to find another one unless I have a significant amount of flight instruction hours,” he said.

Andrews' story is similar to that of many aspiring pilots who face barriers to completing training, but he hasn't lost sight of the end goal.

“I just keep thinking of that little boy on that jet,” he said.

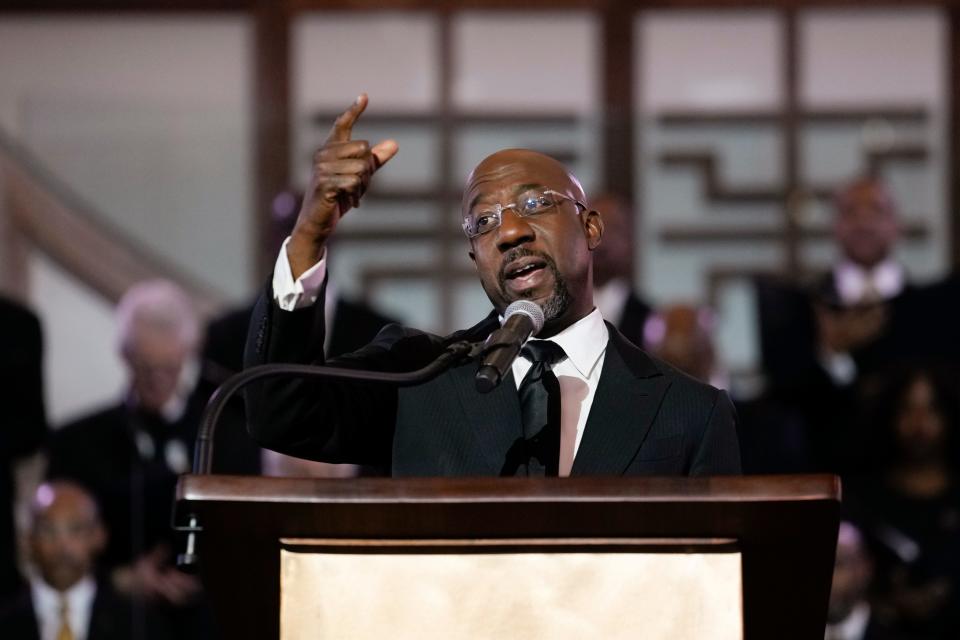

Warnock, lawmakers talk solutions

Sen. Raphael Warnock, D-Ga., is one lawmaker looking to address the workforce challenges in the aviation industry that are contributing to the pilot shortage. He met with Andrews to hear his story at the DeKalb-Peachtree Airport in Chamblee, Georgia, last April.

“He had that passion in his eyes that you’d like to see when you encounter a young person who has found what they were put here to do,” Warnock said.

The Georgia senator said the shortage of pilots, air traffic controllers, mechanics and aviation technicians is an opportunity to prepare the future workforce.

“We don’t have enough pilots, and the only way to address that is to broaden the pipeline and to provide the resources that we need so that young people who are ready like him can get the training,” Warnock said.

Warnock introduced the AIRWAYS Act— the Advancing Inclusion and Representation in the Workforce of Aviation and Transportation Systems. The bill establishes a grant program to support the education, recruitment and workforce development of aircraft pilots and technicians, encourages participation of underrepresented populations in the airline industry and strengthens aviation programs at minority-serving institutions.

“We’re not going to be able to respond adequately to the shortage if we don’t create pathways for young people regardless of their income and their ZIP code,” he said.

Warnock said the aviation sector, specifically related to pilots, is “woefully underrepresented” in terms of diversity.

“I think people make a mistake when they see the issue of diversity as somehow separate from the workforce shortage," he said. "I think those are two sides of the same coin.”

Congress turns to yearly FAA authorization

There have been efforts in both chambers to address workforce development in the airline industry as Congress looks to authorize FAA funding before it expires at the end of September.

But not all solutions come without controversy.

The House passed its version of the FAA reauthorization bill, which:

Improves recruitment and retention of industry workers.

Increases hiring targets for air traffic controllers.

Establishes workforce development programs.

Raises the retirement age from 65 to 67 for commercial pilots.

Some lawmakers, as well as pilot union groups, oppose the measure raising the retirement age.

"This terrible policy puts us completely out of sync with our partners in Europe and would cause myriad issues for training, scheduling and could even require reopening pilot contracts," Rep. Pramila Jayapal, D-Wash., who chairs the House Progressive Caucus, said in a statement.

Lawmakers in the House also debated a provision that would relax the minimum experience and training requirements to serve as a professional airline pilot, but it was struck out of the House’s final version of the bill.

The Senate is now working on its own version of the FAA reauthorization. Jayapal encouraged senators to eliminate the provision raising the pilot retirement age.

The Regional Airline Association, an association representing North American regional airlines and non-airline members, applauded the move in the House to raise the retirement age.

"While long-term policy solutions must continue to focus on pilot training and career access, short-term solutions are needed today to mitigate against further air service collapse," Regional Airline Association President and CEO Faye Malarkey Black said in a statement.

Warnock called raising the retirement age and reducing training requirements “Band-Aid” solutions to the workforce development problem.

“When you’re sitting on a tarmac, hoping the plane takes off or sitting at a gate waiting on a pilot, nobody asks is the pilot a Democrat or Republican,” he said. “I think we need to get politics out of the way and bring forward common-sense solutions.”

Don't blame the ones who showed up: Pilot shortage driving airline reliability struggles this summer

Solving the shortage

Tajer, the spokesman for the Allied Pilots Association, said changing requirements like the retirement age for pilots or the experience and training guidelines could have a significant effect on the airline industry's safety record.

In addition to the Allied Pilots Association, the Air Line Pilots Association, which represents 74,000 pilots, and the Southwest Airlines Pilots Association, which represents 10,000 pilots, do not support increasing the retirement age or lowering the bar for training to get pilots onto the flight deck.

To Tajer, who has spent 30 years as a pilot, increasing the retirement age by two years is an area that is unstudied, untested and unnecessary. The International Civil Aviation Organization does not allow pilots older than 65 to fly, meaning American pilots in that age category would not be able to fly internationally.

“It likely will not resolve this pilot staffing problem ... and if it did, it would be marginal and only short-lived because it’s a two-year extension,” Tajer said.

Solving the pilot shortage starts in the pipeline, Tajer said. He pointed to systemic problems like prospective pilots who often have to take out commercial loans for flight hours, facing higher interest rates compared with education loans.

“The real solution to this is not only improving the financing and the ability for not just someone who has the wealth to do it in their family and making that loan manageable, but it’s actually connecting the pilot to the flight experience they need so that there’s a smooth transition,” he said.

Tajer said the industry has been divided between those who have the resources needed to become a captain with a major airline and those who do not have those resources, which keeps diversity out of the industry. Similar pressure points exist for air traffic controllers, mechanics and ground workers who all play an important role when it comes to safety, he said.

“This is what happens when you don’t tend to the pipeline and then you turn on the faucet and expect to have a good flow and there’s only a trickle coming out.”

What about air traffic controllers?

A June audit from the Department of Transportation Office of Inspector General found that air traffic control centers are facing staffing shortages that pose threats to the country’s airspace.

According to the audit, which was done from November 2021 to April 2023, at least 20 out of 26 – or 77% – of crucial facilities are staffed below the FAA's 85% threshold.

The COVID-19 pandemic led to a backlog in training. The suspensions and refresher-training requirements have added to controller certification times.

The shortage is leading air traffic controllers to often work overtime.

'Only going to get worse'

Airlines and union representatives have acknowledged the shortage in recent years.

United Airlines CEO Scott Kirby said in April last year that the pilot shortage for the airline industry is a real challenge.

“Most airlines are simply not going to be able to realize their capacity plans because there simply aren’t enough pilots, at least not for the next five-plus years,” CNBC reported he said during a quarterly earnings call.

Also last year, Casey Murray, president of the Southwest Pilot Association, told Yahoo Finance that fewer people are entering the pilot ranks.

“This is going to go for the rest of the decade, and it’s only going to get worse.”

Contributing: Zach Wichter

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Turmoil at airports: How Congress is trying to fix the pilot shortage