The end of the imperial governorship

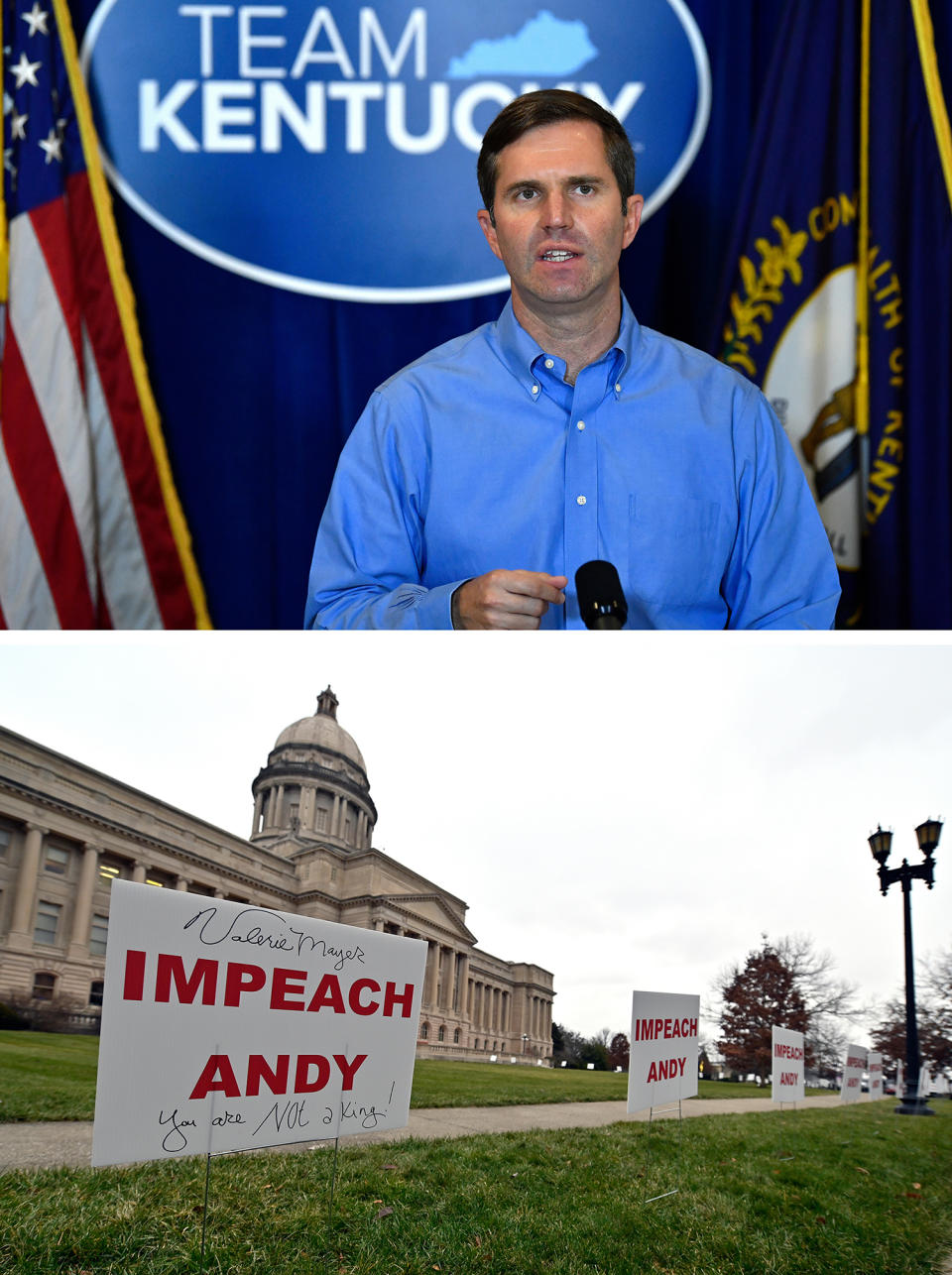

One of the first things on the agenda this year for Kentucky Republicans was figuring out how to kneecap Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear. They dropped legislation in January that placed new limits on the governor’s emergency executive powers, quickly passed the bill, overrode his veto and then fought him in court.

In the months that have followed, lawmakers across the country — from Maine to California, Oregon to Florida — have proposed and, in many cases, passed similar measures to curtail the sweeping powers bestowed on their state executives.

The tug-of-war between legislators and governors has the potential to shape the boundaries of gubernatorial authority for years to come and raises substantive questions of how much leeway the state leaders should have during prolonged crises.

Fiery debates over things like mask mandates and other economic restrictions were frequent last year, particularly in battleground states and those with divided state governments, as public health debates were imbued with election year considerations. But the conflict over the power of the executive transcends ordinary politics, playing out in states both red and blue, and even where one party controls both branches.

Lawmakers are only now realizing how much power they cede to the executive — and are attempting to reassert themselves in blunt ways. If 2020 marked the rise of the authoritarian governors, 2021 may be the beginning of their fall.

Republican legislators in Pennsylvania, frustrated with Gov. Tom Wolf, will ask primary voters next month to consider constitutional amendments granting the state’s General Assembly the power to end gubernatorial disaster declarations and require legislative approval for declarations that extend longer than 21 days.

In Kansas, GOP lawmakers already pushed through a law to sunset Covid-19 executive orders issued by Gov. Laura Kelly, a Democrat, and used their new power to reject a statewide mask mandate. Republican Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson has likewise signed a bill giving the legislature more power to check his and future governor’s emergency authority.

In New York, the Democrat-controlled Legislature limited Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s ability to issue new Covid-related diktats — one of the earliest signs of the Democrat’s diminished standing in Albany amid multiple scandals. Lawmakers even denied Cuomo political cover by rebutting his claim that he played a role in brokering the legislation.

And in Ohio, Republicans last month successfully overrode party-mate Gov. Mike DeWine’s veto of a bill that gave lawmakers say over numerous emergency and health orders.

“We can’t leave it up to one person — no matter how much we like him or her — and everyone else who was elected has to sit on our hands,” Ohio Senate President Matt Huffman, who made the issue a priority after assuming the top leadership spot in January, said in an interview. “That’s not how it’s supposed to work in a republic.”

As former President Donald Trump took a hands-off approach to the pandemic, bristling at any sort of forceful restrictions on public life, governors across the country flexed their muscles and exerted themselves in ways unprecedented in recent memory as they battled Covid-19.

Many state leaders have long had extraordinary powers to respond to crises, in some ways exceeding the domestic reach of the president. The pandemic won them even more authority — and exposed the limits of their existing powers — as state leaders took steps that reshaped the lives of their constituents.

Most governors insisted throughout the crisis that they were being guided by evolving science and trying to navigate uncertain terrain as best they could. But patience appears to have worn out for many legislators consigned to the backseat.

Lawmakers in nearly every state in the country have introduced a combined 300-plus bills this year related to governor’s emergency authority or executive action taken during the fight against Covid-19, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Only a fraction of those measures are likely to ultimately move out of committee, let alone be enacted into law, but the bills nevertheless reflect the considerable interest in recalibrating governors’ emergency authorities.

In some states, it has been a continuation of philosophical differences that have played out over the course of the still-ongoing pandemic. That dynamic has been particularly evident in places sporting Democratic governors contending with GOP-controlled statehouses like Kentucky, Kansas and Michigan, where conservative outrage over Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s pandemic mandates put her in physical danger last year.

But for other governors, it has been members of their own party who have been the ones trying to wrestle back control and deliver emphatic rebukes of their state’s leadership, as was the case in New York and Ohio last month. The move against DeWine marked the first successful override since the Republican took office in 2019 — and it came despite his pleading that the legislation “jeopardizes the safety” of residents and “handcuffs” the state’s capacity to respond to crises.

“It’s a bit of hyperbole to say people are going to die because of this because that presumes the legislature will collectively ignore that kind of risk,” Huffman said.

DeWine last week consolidated into one more than a dozen public health orders in order to “simplify” the rules for people, though he denied the changes had any connection to the newly empowered legislature.

A number of governors and their legislative allies have fended off efforts to pare back their authority, though lawmakers are still in session in most states and could still act.

Virginia’s General Assembly wrapped without taking up the issue as lawmakers head into an election year, and Connecticut legislators recently extended Gov. Ned Lamont’s emergency powers another month, to May 20.

Max Reed, Lamont’s communications director, attributed that extension to the sense of collaboration between the two branches of government, both of which Democrats control in Connecticut.

“Maybe there is a different understanding in states about what they’re facing when it comes to these emergencies,” Reed said. “We’ve had a mutual understanding about what’s been going on with our response and the economy."

Many governors saw their standing rise and fall — sometimes more than once — in the minds of their constituents as they charted through uncertain terrain over the past year. At times, they enraged religious leaders, business owners, public health officials and even members of their own political party.

The battle between legislators and governors was a major factor in the varying ways that different parts of the country responded to the pandemic. It has been somewhat overshadowed as states begin to lift restrictions — occasionally against the advice of public health experts — and national headlines are dominated by Republican-driven efforts to overhaul election laws and target how transgender youths are treated.

After Democrats failed to break GOP majorities in a single legislative chamber, and Republicans failed to supplant Democratic governors in places like North Carolina, the focus quickly shifted to altering the balance of power in state capitals with regards to pandemic policymaking.

“We all want to make sure that the governor is able to act quickly in emergency situations, but we need to think about what constitutes an emergency,” said Massachusetts state Sen. Diana DiZoglio, a Democrat who has introduced legislation to limit the powers of Republican Gov. Charlie Baker. “The governor has not signaled any intention of giving up his powers and the legislature has to be the check on the administration.”

Generally speaking, however, the GOP has tilted far more toward limiting what governors are allowed to do by law than Democrats to date.

Take the moves in Kentucky, where Beshear remains popular and last week signed a GOP-blessed bill to loosen early voting laws. Among other things, the laws passed by Republicans — which the governor’s office quickly challenged in court — place a 30-day limit on executive orders issued during a state of emergency unless ratified by the General Assembly, requires permission of the separately-elected attorney general before suspending existing statutes and bars the governor from altering election laws during an emergency.

“If he were a Republican, he would have been nominated for the Nobel Peace prize,” said Kentucky Democratic Party Chair Colmon Elridge, who previously served as an adviser to Beshear’s father, a former governor. “There is a time and a place to have those conversations, but with a little bit of time passed to assess the utilization of those powers.”

The courts have also struck down some of the ways that governors have tried to wield their powers. In some cases, top lawmakers were the ones leading the legal effort against the executive branch and local health departments.

At the end of March, the Wisconsin Supreme Court nixed Gov. Tony Evers’ ability to impose a statewide mask mandate in voting 4-3 that he ran afoul of state law by stringing together emergency declarations to prolong the mandate without approval from the GOP-run legislature.

And Michigan lawmakers cleared the way for a potential legal showdown after Whitmer vetoed legislation yoking new time limits on emergency orders issued by the state health department to nearly $350 million in Covid-19 testing funding. Earlier in March, legislative Republicans authorized Senate Majority Leader Mike Shirkey to sue the Whitmer administration if it attempted to spend money tied to such legislation.

“Executive fiat has not worked for Michigan,” state Sen. Lana Theis, who sponsored the vetoed bill, said in an interview. “We are supposed to be the voice of the people and we were elected to be that voice. How long do you get to go with a unitary executive?”

Whitmer has said the Republican legislature is playing a “dangerous game” by trying to leverage the money against her.

Similarly, Indiana Gov. Eric Holcomb, a Republican, on Friday vetoed a bill that would allow the legislature to call itself into special sessions during emergencies as a way to revoke gubernatorial edicts. Holcomb said he believed the provision was unconstitutional.

The situation has not always been so contentious, even though governors are instinctively reluctant to cede to any encroachment on the powers vested in their offices.

Utah Gov. Spencer Cox, who had been second-in-command to the term-limited Republican Gary Herbert before winning the governorship in the fall, managed to negotiate with Republican lawmakers on a timeframe to lift mask mandates and pare back the governor’s emergency powers going forward.

Rather than attempt to stymie the legislation wholesale, Cox’s office kept in close contact with lawmakers throughout the legislative process and helped secure several changes to the final bill language, Senate Majority Leader Evan Vickers said.

“There’s reasonable allowance to let the governor operate on a daily basis, so we didn’t interrupt anything on things like tornados or a chemical spill, and even on long term stuff they have room to operate,” Vickers said prior to the bill being signed into law.

Vickers said the negotiations helped head off moves by some lawmakers to further restrict the governor’s powers to combat the present crisis and engendered Cox some goodwill early in his term.

“The governor was working along with us even if he didn’t always agree with us,” he said. “I think we landed in a good spot.”