The end of a pandemic-era boost to SNAP benefits is compounding the burden low-income households already face

A pandemic-era boost to the funds low-income households receive to buy groceries is ending, setting the stage for a potential rise in food insecurity.

For nearly three years, an emergency allotment has provided households that participate in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, with at least $95 extra per month to spend on food.

Eighteen states have already halted the additional allotments. At the end of February, the remaining 32 states and Washington, D.C., will follow, putting a financial strain on people already struggling to make ends meet.

“I’m not worried that I won’t be able to make it, because I will be,” said Tanisha Ferran, a Wooster, Ohio, mother who can’t work because of chronic back problems. “But it will be, like, by the skin of my teeth every month.”

In states that have already stopped the allotments, anti-hunger advocates say there has been a noticeable rise in hardship among food-insecure families.

Georgia ended emergency SNAP allotments after May. At the Atlanta Community Food Bank, which serves 29 counties, visits increased by about 34% from July through December compared to the same period the previous year, said its president and CEO, Kyle Waide.

Waide attributed the increase in demand to the loss of the allotments, as well as the end of other pandemic-era measures, such as the child tax credit and universal free school meals.

“We’ve been worried about lines’ getting longer at food pantries for a variety of reasons," he said. "And as it turns out, those worries and concerns were well-founded.”

The SNAP emergency allotments were never intended to be permanent. They were supposed to last until the federal government declared an end to the Covid public health emergency, which the Biden administration announced this week would be in May. But instead, a last-minute provision in the government’s omnibus spending bill curtailed the SNAP surplus after February.

Grocery prices continue to increase, despite cooling inflation. The Agriculture Department’s Economic Research Service forecasts that food prices will rise by 4.2% to 10.1% this year compared to all of 2022.

“Everybody toward the bottom of the income scale is just facing really significant economic pressure right now,” Waide said. “The discontinuation of these programs, in some ways, couldn’t have come at a worse time.”

‘A lousy thing to do to poor people’

SNAP, formerly known as food stamps, is a far-reaching public assistance program: More than 42.3 million people across the U.S. participated in October, the most recent Agriculture Department data shows.

Eligibility is based on income, among other factors, with $253.43 being the average monthly installment for a SNAP participant in October, including the emergency allotment. Benefits are distributed once a month.

With the end of the allotments, SNAP benefits return to a format that anti-hunger advocates say was insufficient to begin with. The average SNAP household uses more than three-quarters of its benefits by the middle of the month, pre-pandemic data found, often leaving participants without enough money to cover the basics between payments.

Rep. Jim McGovern, D-Mass., the ranking Democrat on the Rules Committee and a champion of anti-hunger efforts, has fought for increased SNAP benefits. McGovern said that without the allotment, he worries that the U.S. is “going backwards” in its goal to end hunger by 2030.

“Ending the emergency SNAP allotment is bad, and it’s a lousy thing to do to poor people in this country when inflation is still a reality and food prices are high,” he said in an interview. “The SNAP benefit, even with the emergency allotment, quite frankly, isn’t adequate.”

The omnibus bill terminated the SNAP allotments early as part of a tradeoff that created a permanent federal summer assistance program for children who qualify for free or reduced-price school meals.

McGovern and others have argued that the programs should be allowed to co-exist.

“If this was the defense budget, no one ever has to decide between, you know, two missile systems,” he said. “They just build them both.”

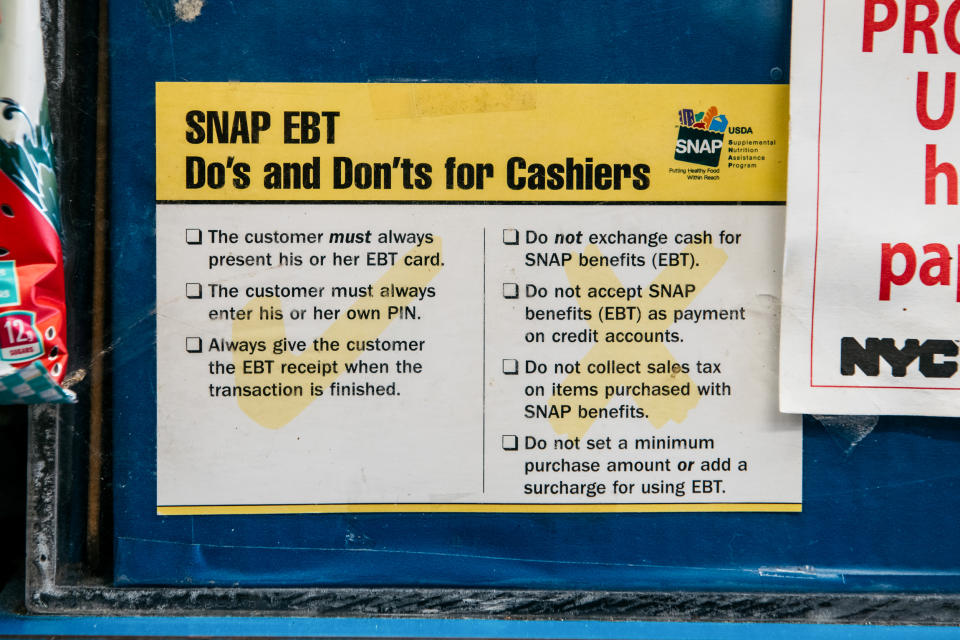

Still, anti-hunger advocates have lauded the creation of a permanent program during the summer, when low-income children often struggle to get nutritious food. The program will enable the families of about 30 million children nationwide to receive $40 per child a month to spend on groceries with via electronic benefit transfer, or EBT, cards.

“Even though it’s very frustrating that they were funded by ending the emergency allotment early, Congress did take dollars from a very temporary program to create permanent benefits for these kids,” said Lisa Davis, the senior vice president of the No Kid Hungry campaign at Share Our Strength, a nonprofit organization working to end hunger and poverty. “It’s still a very positive thing on balance.”

But some say other vulnerable populations are being overlooked.

Pauline Doty, 74, lives alone in Columbia, South Carolina, where emergency allotments lapsed at the end of January. With the emergency allotment, she hasn’t had to visit a food bank in the last three years, but she said she may need to go now that her monthly SNAP benefits have decreased from over $200 to $39.

“Thirty-nine dollars doesn’t hardly pay for even half a week of food,” she said. “I’m going to have to be more careful every time I shop.”

Doty monthly benefits dropped because the emergency allotment went away and because a bump in her Social Security benefits meant she qualified for less in SNAP funding. Her Social Security benefit is up by $80, which doesn’t make up for the loss in her SNAP payments.

The government recently issued Social Security beneficiaries the largest monthly cost of living increase in 40 years, which has had consequences for other seniors who are on SNAP, as well, disqualifying some of them from receiving SNAP altogether.

A much smaller SNAP payment requires Doty to change her purchasing habits. During the pandemic, the extra allotment allowed her to stock up on groceries and buy healthier food, including fresh produce, she said. Now, she will have to dip into her monthly Medicare and Medicaid payments for groceries, taking away money she had previously designated for products like over-the-counter medicines, supplements, shampoo and lotion.

“There have to be better solutions,” she said.

Low-income households across the country are certain to face the same dilemma, anti-hunger advocates said.

“Those families have to figure out where they’re going to pull from to be able to fill those gaps,” said Eric Mitchell, the executive director of the Alliance to End Hunger, a coalition of over 100 groups working to address the root causes of hunger. “Oftentimes those are the choices that families have to make — difficult choices between food and medicine.”

Michelle Sellers, 52, of Wayne County, Ohio, has diabetes and is concerned she won’t be able to eat the proper foods to manage her condition.

Just because the pandemic is no longer considered a public health emergency doesn’t mean people can buy the food they need, she said.

“This is not just a Covid issue,” Sellers said. “This is a hunger issue that’s been going on.”

An uncertain future for SNAP

Those advocating on behalf of low-income households hope to see an increase in SNAP benefits from the coming farm bill — or at least no further cuts. But it’s not clear which direction the farm bill will go.

The sweeping spending bill, which funds SNAP and some other federal food assistance programs, expires at the end of September, and it will need to be reauthorized. When it was last reauthorized in 2018, SNAP work requirements and other eligibility restrictions were sources of contention.

Those who resist expanding SNAP, McGovern said, “should all try living on a SNAP budget,” adding, “You can’t.”

Doty agrees. She said she’s grateful for the surplus funds she received for nearly three years.

“It was very, very, greatly appreciated and needed,” she said. “Now, I just would say there will be many people who have less and who need more.”

CORRECTION (Feb. 3, 2023, 11:48 a.m. ET): A previous version of this article misstated that Pauline Doty had never visited a food bank. She has, but not since she received SNAP emergency allotments. The article also misstated the position of Rep. Jim McGovern, D-Mass., on the House Rules Committee. He is the ranking Democrat, not its chairman.

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com