Can English unite a divided America? A Mexican American scholar weighs in

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The story of American English is how the nation’s different groups have made the language their own — but it’s also about the way it connects Americans.

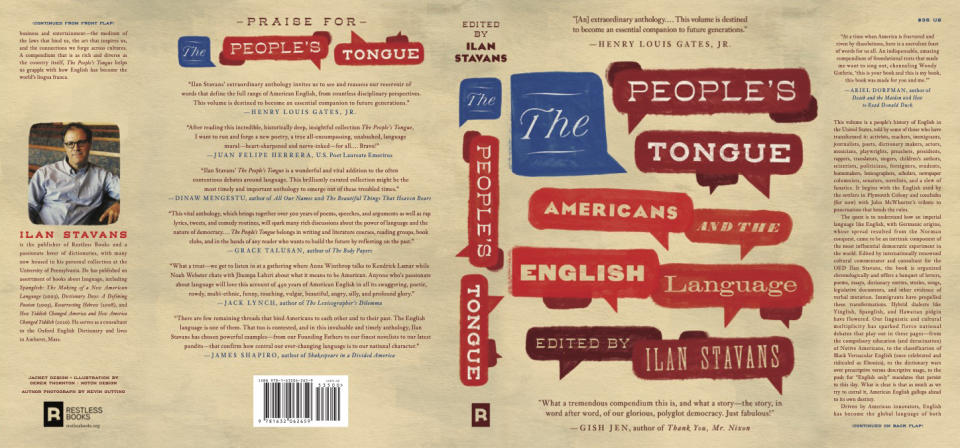

The latest book by the Mexican American author and scholar Ilan Stavans, “The People’s Tongue: Americans and the English Language,” looks at how American English has set and pushed boundaries for more than four centuries — and become a global language.

“We live in a time when the country is dramatically fractured and polarized. And some people can’t even see each other face to face,” Stavans said in an interview. “But while one group uses English in one way and others use it in different ways, we are all still speaking the same language, which is the language that is being projected from the United States to other parts of the world.”

The power of American English, from the speeches of President Abraham Lincoln to modern-day rap lyrics and even former President Donald Trump’s tweets, are all part of the nation’s powerful identity.

“The People’s Tongue” is an anthology, curated by Stavans, that includes articles, essays, poems, songs, stories, excerpts from novels, speeches, tweets and other milestones of American writing that show how the language has changed from the early settlement days of the 1600s up to 2022.

“To create a new nation, you need a language,” Stavans, who’s a consultant to the Oxford English Dictionary, writes in the introduction. “Other ingredients are also required in forging a nation: a territory, a flag, a government, a currency, a postal service, and so on. Language, however, is the crux. Without it, you have no conversation.”

In the introduction, Stavans, who grew up in Mexico speaking Spanish and Yiddish, describes his experiences learning English in New York almost four decades ago.

“My first exposure to its multifarious character was in the New York City subway, attuning my then innocent ear to the intermingling tonalities of a typhoon of tongues,” he wrote about the diverse influences that feed into American English.

Some highlights from the book are Noah Webster’s preface to his two-volume dictionary of American English, a letter from the Native American author and speaker Simon Pokagon about Indigenous voices reacting to imperial power in English, an essay by the novelist James Baldwin about Black English and a poem by the Dominican American writer Julia Alvarez exploring what it’s like to be bilingual in Spanish and English. It even includes a compilation of Trump’s tweets from 2015 to 2021 that were directed exclusively at the television network CNN.

Stavans describes the English language as a space where history, politics, religion, science, business, technology and other cultural influences have set and pushed the boundaries of American identity. And he says that during those conversations and arguments, which have spanned multiple generations, Americans discovered their humanity by speaking the English of their communities.

“At the very center of ‘The People’s Tongue’ is a question: ‘Who is in charge of the English language, and who decides what’s correct and proper and what isn’t?’” he said.

From ‘colonial language’ to American

“The great struggle that this country goes through is that of turning a colonial language into its own language," said Stavans, to supersede the empire that colonized it.

“But within two centuries, this colony-turned-nation will itself want to be an empire that will bring its language through Hollywood, technology and business to other parts of the world," he said.

Part of the answer, Stavans says, can be found in the historic tensions between the British Empire and the U.S. and how Americans forged early identities through the friction between the colonies and the empire, the monarchy and a new democracy.

“This is an inherited language from England,” he said. “But early Americans are also thinking about what we can do, if we’re breaking away from England, to break away from the English language of the British monarchy.”

For early Americans, that meant rethinking English from a language of empire to a language of empowerment.

To demonstrate the point, the book includes a proposal by Founding Father John Adams (before he became the second president of the U.S.) calling for the creation of an American Language Academy to reinforce the democratic values and character of Americans.

“It is not to be disputed that the form of government has an influence upon language, and language in its turn influences not only the form of government, but the temper, the sentiments, and manners of the people,” Adams wrote.

Stavans sees the relationship between language and government as a driving force that has shaped the identities of multiple generations of Americans, from the War of Independence to the Civil War to even current legislation about immigration.

In a nation where social mobility — while debatable — is the norm, Stavans said in a follow-up email, the types of American English — such as Spanglish, Chinglish, Black English — move up into the middle class as people assimilate. These varieties empower its speakers, allowing them to project their identity into the mainstream.

As an example, Stavans said, Latinos can share many common experiences, but they are also very diverse, including when it comes to language.

“There are Latinos of all kinds, in terms of class, race, age, gender, education, nationality and, of course, politics,” he said. “For starters, liberals and conservatives call themselves by different names: Latino Democrats and Hispanic Republicans.”

Embracing English — and Spanglish

But speaking English does not mean becoming English-only Americans. Stavans compares groups like Latinos today with early American revolutionaries who used English as a tool for empowerment.

“The forces within our minority have led us to abandon Spanish in order to be more successful or more patriotic,” Stavans said. “But there is a current in the book that I hope is clear and loud — how we have also been bilingual and what bilingualism has allowed us to achieve.”

Americans dress themselves “by using a particular lexicon,” which he compares to clothes one wears as a form of identification.

A popular example of a Latino lexicon, featured in the book, is the Spanglish adaptation of the poem “A Visit From St. Nicholas,” often better known as “The Night Before Christmas”:

“The stockings were hanging with mucho cuidado

“In hopes that abuelo [grandpa] would feel obligado

“To bring all the children both buenos and malos [good and bad]

“A nice bunch of dulces [candies] and other regalos” [gifts].

For comparison, the original poem, which dates to the 1800s, says:

“The stockings were hung by the chimney with care,

“In hopes that St. Nicholas soon would be there;

“The children were nestled all snug in their beds,

“While visions of sugar-plums danced in their heads.”

Spanglish, Stavans said, “used to be ridiculed a decade ago; today it is not only a source of pride but a way into the labor market, as well as a mechanism to expand American culture — from within.”

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com