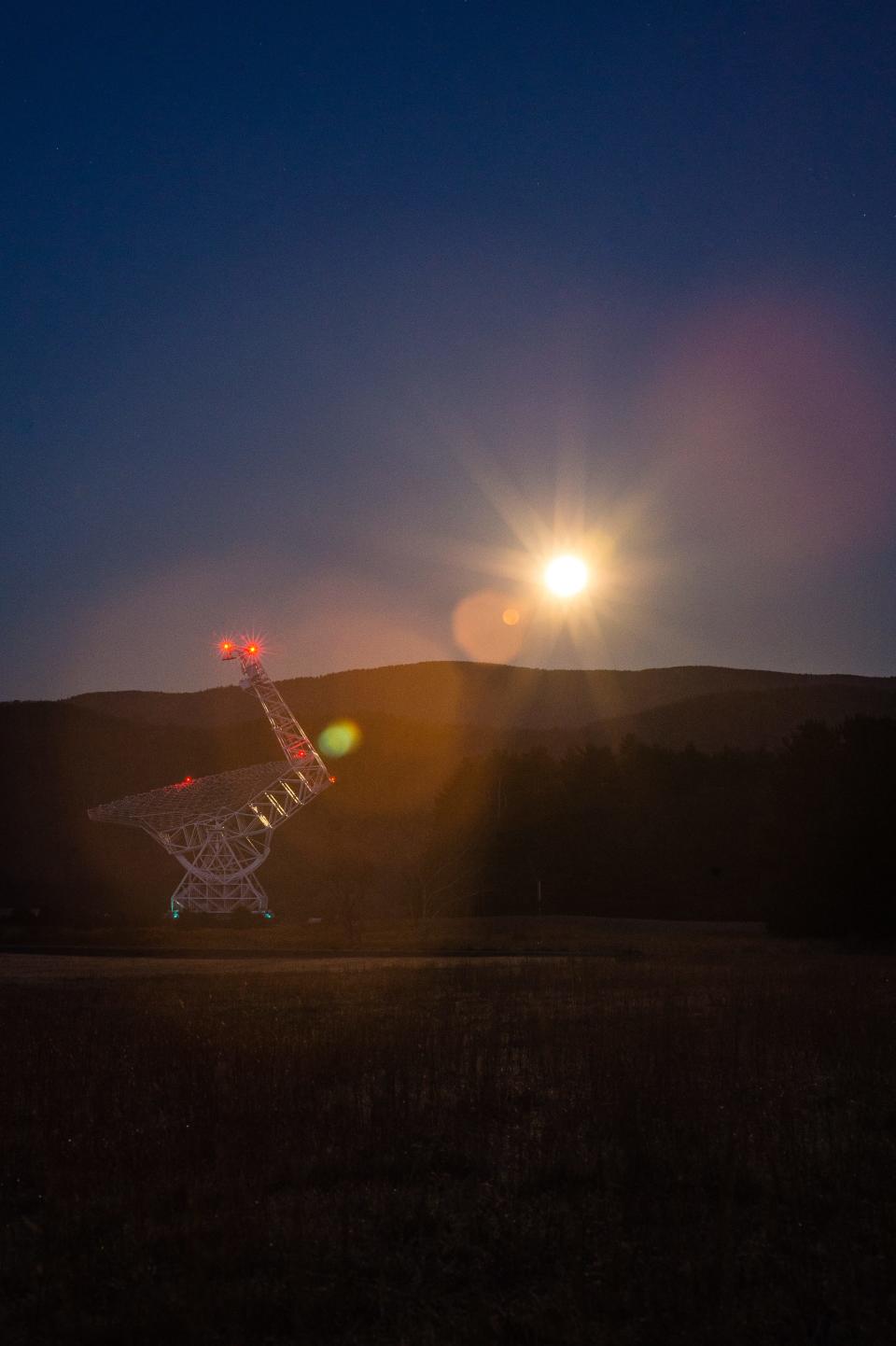

Enjoying the eclipse is priceless, but getting professional-looking photos is expensive

TUSCARAWAS COUNTY – So, you want to photograph this year’s total solar eclipse, huh?

This astronomical event is surely one not to miss, but if you’re looking to capture it in all its glory, you will likely need some pricey photographic equipment if you want to approach what the professionals have trained for and hope to capture perfectly.

In order to visually eclipse the fabled Goldilocks Zone – forgive the pun – in which conditions are just right for water to remain liquid, you’ll need to accomplish three things: bring both the sun and moon a lot closer by magnifying them; protect the camera sensor before and after totality (assuming you’re not using film – a different discussion entirely) with a dense solar filter that blocks out most visible light; and stabilize the camera and lens with a tripod.

Assuming you are prepared to do all that, some research will also need to be done to dial in the proper camera settings so that you are not futzing around while the event is happening. Trust me, if you are doing that, those three-or-so minutes of totality will pass by before you realize it.

The proper professional lens to do this right typically costs north of $10,000 if you are looking for a high-quality, highly magnified photograph of the eclipse. Camera bodies capable of taking a solid picture are pricey, too, as is the tripod needed along with a star tracker (if that's your thing) which will move your rig to track the sun and moon as they transverse the sky, so you do not have to worry about making a physical mistake ruining your once-in-a-lifetime photographic opportunity.

It’s what we do

Photographers can be a notoriously fickle bunch when it comes to the business of knowing exactly what they want to photograph and how. When it comes to astronomical photography, or capturing anything having to do with heavenly bodies, adding the scientific component can make us downright snobbish. A lot of that has everything to do with planning and timing, because if your calculations are in the least bit off the shot will get missed.

Can you use an iPhone?

What about my iPhone? Can’t I use that, you ask? Well, again, you face some considerable technological constraints around distance and exposure for a bright object you cannot safely look at with the naked eye or through a smartphone without causing severe damage.

A lot of photographers use a familiar phrase when criticizing photographs that are not as effective or evocative as they could be: get closer. This typically means you are just too far away for that photograph to be meaningful, or you have not successfully made a good with the subject being photographed – usually a person. So no, your camera phone is not going to do you a lot of favors either.

A really good photographer once had a key piece of advice for me after a portfolio review, during which he said, “Sometimes the best photographs are the one’s behind you.”

Sometimes, when professionals are looking for poignant moments in time to photograph, there is something happening 180 degrees in the opposite direction. So if you are up to the technical chore of capturing the eclipse itself, focus on other things going on around you. Embrace all the glory of what will be happening on the ground and in the sky that is not the eclipse. There will be plenty of aha moments to capture, or downright laugh-out-loud moments that you will be able to look back upon with fondness. And if you have family planning on sharing in the celebration of the event, all the better.

In a recent article published by EarthSky, NASA photographer Bill Ingalls said, "The real pictures are going to be of the people around you pointing, gawking and watching it. Those are going to be some great moments to capture to show the emotion of the whole thing."

Look for those kids with pinholes punched in shoeboxes used to view the eclipse safely or someone with a colander projecting the eclipse onto the pavement. If there’s decent foliage on the trees, the event will also provide fun to observe shadows cast on solid surfaces. There are watch parties to be found along the path of totality that you could attend. Or just lounge in your backyard wearing your certified viewing glasses and take some selfies for a good laugh.

Of course, here in Ohio, there is a high probability of partial or total cloud cover. That too, is part of the experience worth photographing in my humble opinion.

A personal family history

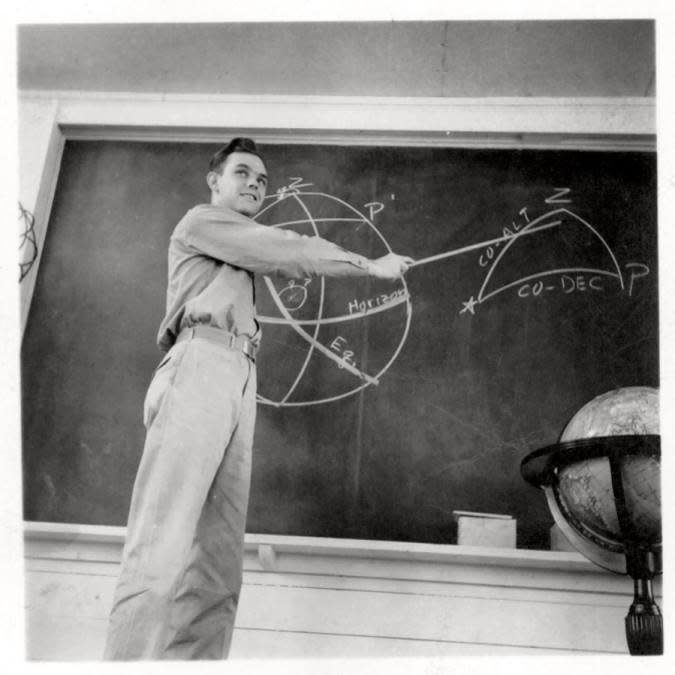

My grandfather figured out how to do it in 1962, on film.

I can trace my personal interest in photography back to my childhood growing up in San Jose, California. My grandparents lived just to the northwest, in Palo Alto, not too far from where Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak had a garage that predated the formation of Apple Computer. My grandfather, Carroll Sears Rankin, was the consummate family historian and documentarian. While he did not always have a camera in hand, he frequently used a Pentax K1000 manual focus film camera. I fondly remember playing the role of navigator when we took trips to drop off rolls of film at the local camera store.

Grandpa was a World War II veteran of the Army Air Corps, having flown 38 combat missions as a navigator over the South Pacific in various B-42 Liberator models. He saved everything from the war, down to his flight logs replete with handwritten notes. At one point, he even taught navigation in Hondo, Texas, and was photographed doing so for an article in Life Magazine. So, I like to think that scientific knowledge equipped him a little better than the average person to accurately measure just where the sun and the moon were going to be at the right time.

On a trip back home to San Jose a few years ago, my mom and I were thumbing through his collection of slide carousels and I noticed one that said, “Eclipse 1962.” I plucked it out and took a quick picture of me viewing. I wish Grandpa were here to tell the story of how and why he photographed that eclipse, and of course to offer me a little navigational advice as I embark on my journey to documenting April 8, 2024.

Technical advice

For those truly interested in photographing the eclipse, there is lots of resources online to help you through the process, and, no, it is not too late to figure it out. With the proper safety equipment in place, you can do tests photographing the sun to get comfortable with the process. You'll need to adjust the focusing ring of your lens manually on a pre-determined infinity mark on the lens barrel. A lot of contemporary lenses do not have those printed on them anymore, so it all must be done in camera through the viewfinder. After putting on the front solar filter, you can verify the exposure by shooting the sun, which will almost blacken the view depending on the density of your filter. Looking for sun spots to focus on will help achieve desired sharpness.

And remember, do not look at the sun without proper eye protection or a solar filter securely attached to a camera lens. I cannot stress this enough.

Because of the aforementioned variables and more, I think it is useful to provide some helpful links, rather than getting too wonky here.

The American Astonomical Society has a guide to acquiring safe solar viewers and filters: eclipse.aas.org/eye-safety/viewers-filters

The society also offers a definitive how to – my personal favorite guide on photographing the event: eclipse.aas.org/imaging-video/images-videos

The standard planning tool to plan and map out your outdoor photographic excursions in natural light is hands down the Photo Ephemeris, online or as a standalone app: photoephemeris.com

If you really want to use your smartphone, technology has certainly gotten better to do so, and Sten Odenwald from NASA Goddard Space Flight Center has a page devoted to that technique: eclipse2017.nasa.gov/smartphone-photography-eclipse

Looking for something fun to do along the path of totality? Visit a definitive guide, state by state: festivalguidesandreviews.com/solar-eclipse-festival-guide/

If you feel yourself getting frustrated, put it all down and enjoy the momen. Now, where is my colander? I would love to hear about your special plans for eclipse viewing – no matter how far you travel, as well as seeing your photographic results. You can email me at the address listed below.

T-R staff photographer Andrew Dolph can be reached by phone at, 330-289-6072, or by email at adolph3@gannett.com. You can also find him on Instagram @dolphphoto.

This article originally appeared on The Times-Reporter: Getting professional-looking photos of eclipse will be expensive