Enlisting the immune system: mRNA cancer treatment new target for Biden administration

In its bid to fight cancer, the Biden administration this week announced plans to enlist the mRNA technology made famous by COVID-19 vaccines.

The idea is to create a platform of mRNA technologies that could turn the immune system against cancer and other diseases.

In this case, messenger RNA-based technology would be used to turn off and on multiple genes within immune cells involved in cancer, auto-immune diseases, organ transplant rejection and chronic conditions like long COVID. By contrast, existing vaccines use mRNAs to produce specific proteins to be targeted by the immune system ‒ the spike protein of the virus that causes COVID-19, or, with cancer vaccines under development, ones on the surface of tumors.

The new research project led by Emory University in Atlanta will receive up to $24 million from the administration's Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H).

A 'big shift' for cancer treatment? mRNA vaccine shows promise against melanoma

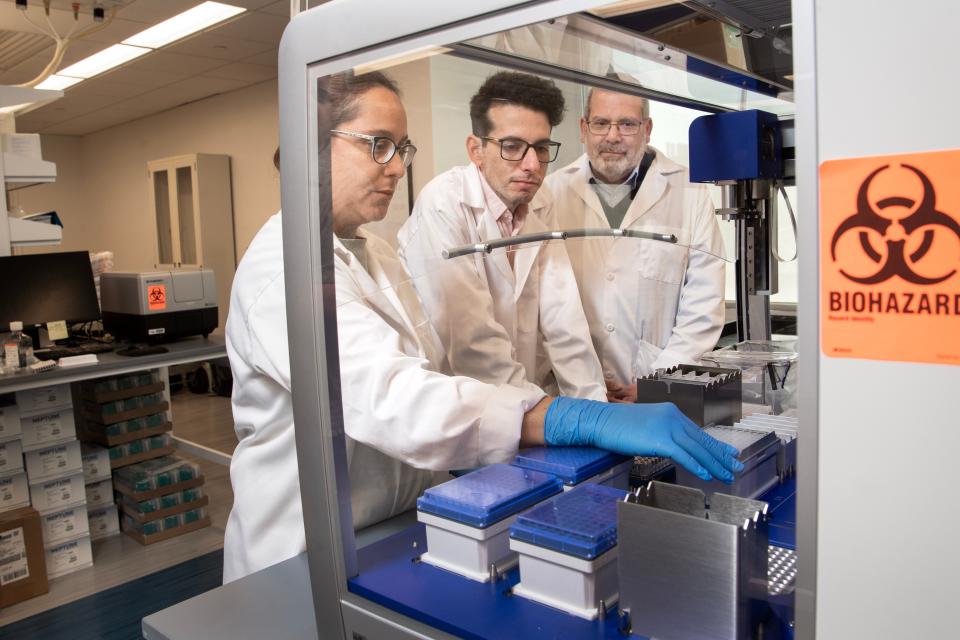

USA TODAY spoke about the new effort with Philip Santangelo, a professor in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Emory and Georgia Institute of Technology, who is leading the work. Below is an excerpted version of the conversation:

Q: What can mRNA do that traditional cancer medications can't?

Most of the tools that exist so far are in some ways are not as complex as they probably need to be. In the case of tumors, we want to make sure that the T cells (the soldiers of the immune system) are better at killing the tumor cells.

There are also cells in the tumors that are very good at turning off the immune system. We need to be able to get at these cells and either get rid of them or prevent them from functioning.

Q: You think this approach will work, not only with cancer, but also for other conditions, like auto-immune diseases, organ transplant rejection and long COVID?

When you go to auto-immune disease and organ transplant rejection, there you need to do the exact opposite (from cancer) ‒ turn down how the immune system is functioning.

One of the issues with long-COVID is sustained immune activation, so how can we go in there and not use steroids, but use our modulators to turn down how the immune system is functioning?

A lot of chronic infections, infectious diseases and cancer look very similar. They can teach other. We can learn from those in terms of how to break the cycle.

Q: In a sense, you're amplifying abilities these immune cells already have, right?

Clear those infections. Clear tumors. It's not that different. We're not making them do things they're not already good at.

Think of it as a piano and we're playing it slightly differently than it was being played before.

This is trying to program the immune system to work better than it has. And I think we can. I think it's doable.

Q: The companies that make the mRNA COVID vaccines are also making cancer vaccines. How are yours different?

We're still using the same basic technology, we're just delivering it differently in order to control how the immune system functions.

Could it be used alongside a Moderna cancer vaccine or a BioNTech cancer vaccine? I think very likely. If anything it would help enhance them.

We needed to take a big, bolder step in order to get the immune system to do what we wanted to do.

Q: These vaccines would be used after cancers develop, not to prevent them, right?

We call these vaccines, but really they're therapies.

We have used them in a more prophylactic-type setting (before cancers develop), but I think they're more powerful when they're used as a therapy.

Q: What do they actually do?

We do not cut or alter anyone's DNA. That would be bad and freak everyone out. We use mRNA because it's transient. It's easier to deliver. It doesn't go into the nucleus (of the cell, where the DNA is). It degrades reasonably quickly.

We want to let it do it's thing, but we don't want that drug to hang around forever and mRNA gives us that opportunity.

‘Watershed moment’: Doctors finding new hope in treatments for deadly pancreatic cancer

Q: What are the potential side effects?

We can use very low doses, which is important for fewer side effects.

Right now I'm not too worried from a safety point of view. But safety is very much a part of our evaluations.

Q: What about cost? Do you expect these to cost more like a very expensive cell-based therapy or a relatively inexpensive vaccine?

This is fast (to make). We're using a very small number of cells, probably a thousand-times less RNA than most vaccines. From a cost perspective, this has the ability to be accessible to everyone.

Q: What would treatment look like? Multiple shots? Infusions?

We do typically dose a few times.

We would draw blood. RNA is delivered to cells that program some of what they're going to do and it's given back to the individual.

You may also get an IM (intramuscluar) shot at the same time to control different aspects of the immune system.

If this were cancer, (the patient would get treated) probably three or four times over a few months and that should do it, I hope. That's the goal.

Q: Other immune therapies work really well for some types of cancers, but not all. Do you expect your approach to work for certain types of cancers?

I think it'll affect more, because we can tailor it for specific cancers.

There's no silver bullet. No one-size fits all. It may depend on the tumor itself. We're trying to develop a big bag of tricks, a better toolbox that can be tailored for a specific tumor.

Q: What can we expect you to have accomplished, say, three years from now?

In three years, we hope to have a few winners that could move forward toward the clinic. That's really the idea. It's not impossible.

Contact Karen Weintraub at kweintraub@usatoday.com.

Health and patient safety coverage at USA TODAY is made possible in part by a grant from the Masimo Foundation for Ethics, Innovation and Competition in Healthcare. The Masimo Foundation does not provide editorial input.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: mRNA, made famous by COVID vaccine, now enlisted for cancer treatment