Enquirer investigation: Cincinnati homicide cases unravel after deals with informants

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Locked up on a murder charge, Quincy Jones wanted to make a deal.

Jones, known as “Q-Ball” on the street, was a heavyset 31-year-old with a gold tooth and a penchant for big talk. He’d been connected for years to a violent Cincinnati gang and his criminal record included robbery, assault and drug charges.

This time, in late 2008, Jones was in the kind of trouble that could send him to prison for the rest of his life. He decided to use the only bargaining chip he had left.

He started talking.

Jones told police and prosecutors in Cincinnati that he knew details about at least a dozen homicides and could help put the suspects behind bars. He would do this, Jones said at the time, because he expected something in return: A plea deal that cut years off his own prison sentence.

“I know how to work this system,” Jones wrote to a fellow inmate at the Hamilton County Justice Center, explaining his strategy. “I’m going to make it work for you too.”

Before his violent death in 2012 – prosecutors say he was shot for “being a snitch” – Jones became a prolific police informant, joining a network of informants and cooperating witnesses who for years helped Cincinnati law enforcement close homicide cases.

The informants sometimes testified in multiple cases and, like Jones, worked with detectives and prosecutors who vouched for their reliability.

But an Enquirer investigation found several of those cases later unraveled, raising the possibility that unreliable informants helped send innocent people to prison and allowed others to get away with murder.

Judges overturned murder convictions and ordered new trials in two cases in which informants provided critical testimony. Another homicide case involving an informant ended in a mistrial, three others with acquittals.

Defense attorneys say prosecutors should’ve seen the problems coming. Instead of being skeptical of ulterior motives, they say, law enforcement embraced informants who made questionable claims in exchange for plea deals and shorter prison sentences.

In some cases, prosecutors agreed to those deals after telling judges and juries during murder trials that the informants got nothing in return for their testimony. Years later, much about the informants’ relationship with law enforcement remains hidden from public view.

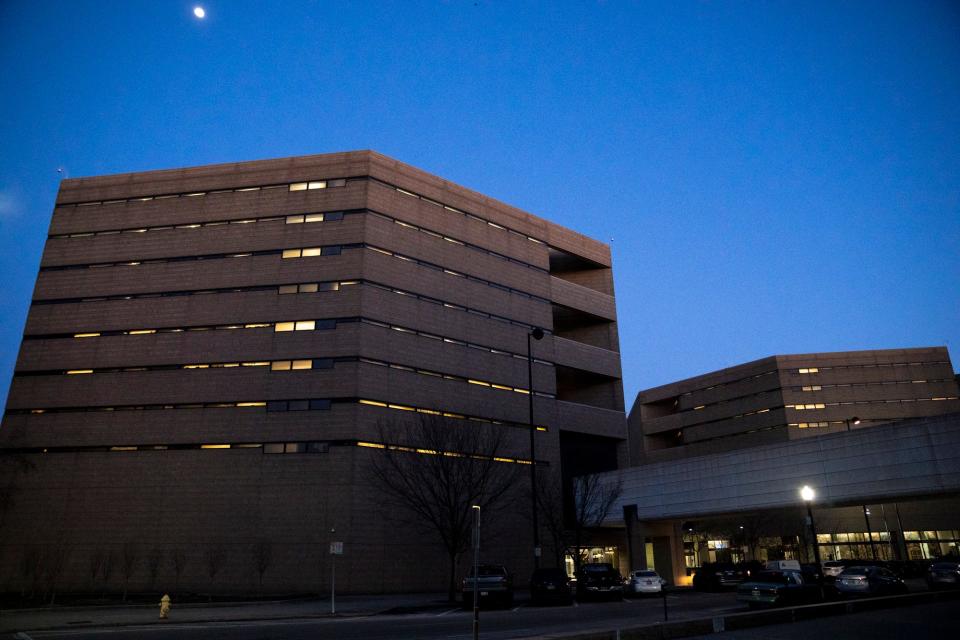

Hamilton County Common Pleas Judge Jody Luebbers, who is overseeing a case coming back for a new trial, expressed frustration in November when prosecutors struggled to provide basic details about Jones’ work as an informant.

“This case is a boondoggle,” Luebbers said during a court hearing.

Hamilton County Prosecutor Melissa Powers acknowledged that informants and cooperating witnesses sometimes help law enforcement because they also hope to help themselves. But she said her office does its best to corroborate the information they provide and uses them only when necessary to keep dangerous criminals off the street.

“It is not an option to decline prosecution of all cases simply because the witnesses involved are unlikable or unsavory,” Powers said in a written response to questions from The Enquirer. “The ultimate goal of prosecutors is to obtain truthful testimony.”

Because there’s no database that tracks prosecutors’ use of informants in trials, The Enquirer spent more than a year analyzing individual cases, looking for instances in which such testimony was relied upon. The review of thousands of pages of court documents revealed how informants convinced law enforcement they deserved a deal in exchange for their cooperation.

The Enquirer's investigation found one informant claimed to have heard a fellow inmate admit to a murder while eavesdropping on him through air vents at the Justice Center.

Another informant’s fingerprint was discovered at the scene of a homicide that he blamed on someone else. Another recanted his accusation on the witness stand, saying he’d been fed details about the crime by a fellow inmate.

And another claimed he witnessed a fatal shooting that occurred while he was miles from the crime scene, locked in his prison cell.

“It’s so unlikely that they were actually hearing so many confessions or incriminatory statements,” said Donald Caster, an attorney with the Ohio Innocence Project who represents a man accused by one of the informants. “It just casts even more doubt on their veracity.”

Yet police and prosecutors kept using the informants. The Enquirer found Jones testified or assisted police in at least 12 homicide cases, including the one in which he was charged.

How much Jones really knew about those homicides is disputed by prosecutors and defense attorneys.

But in the letter he wrote while in jail, sometime in 2010, Jones made clear he saw being an informant as an opportunity to help himself. He advised others to follow his example.

“Do what you gotta do,” he wrote, “to save your neck.”

Trading testimony for a plea deal

Informants are part of the American criminal justice system because they can, in theory, reveal details about a crime that others can’t. They know something, or claim to know something, that can bring a guilty person to justice.

Police and federal agents use informants all the time, often behind the scenes, to solve tough cases and to infiltrate and dismantle criminal organizations.

“These prosecutions make our community safer by removing these criminals from our streets, often breaking cycles of violence and retaliation that wreck our communities,” Powers said.

But relying on informants also can be risky. Unlike other witnesses, informants and cooperating witnesses often have criminal records and personal history with the suspects they implicate in crimes.

Sometimes, they also are directly or indirectly involved in the crimes they help solve, giving them motive to say what police and prosecutors want to hear while minimizing their own roles in those very cases.

The result, experts say, is a greater danger of false testimony.

Nationwide, informants played a role in almost 20% of convictions that later were overturned because of DNA evidence and 15% of overturned murder convictions, according to the Innocence Project and the National Registry of Exonerations.

“They’re unreliable,” said Alexandra Natapoff, a Harvard Law School professor who has extensively studied the use of informants in the criminal justice system. “It is known in the prosecutorial community that they are risky.”

So why risk it? One reason is that informant testimony is the most useful in cases with the weakest evidence, said Natapoff, author of “Snitching: Criminal Informants and the Erosion of American Justice." If prosecutors can rely on clear evidence of DNA, fingerprints or unrewarded eyewitness testimony, they can avoid using informants.

“The weaker the case, the more valuable an informant,” Natapoff said.

For defendants and their lawyers, challenging an informant’s credibility can be difficult. They can ask in court whether prosecutors promised a deal in exchange for testimony, but those deals often are confidential or don’t spell out terms in writing, allowing informants to say they haven’t been promised anything.

That lack of transparency makes it difficult to connect informants to cases. The Enquirer made those connections by interviewing attorneys and defendants in homicide cases and then reviewing court documents, subpoena records, transcripts and other sources to find out how Jones and other informants operated and how often they worked with law enforcement.

For Jones, the pursuit of a deal began with his arrest on murder charges in 2008. Prosecutors accused him and three others of killing two men, including Cleveland Parker, a 57-year-old grandfather who died in 2005 after a stray bullet struck him in the chest as he watched TV in the living room of his Walnut Hills home.

Even before his arrest, Jones was no stranger to police and prosecutors. His rap sheet was long, and he’d been connected for years to a violent street gang known as the Grimmie Network.

Hamilton County Assistant Prosecutor Allison Oswall last year described Jones this way: “He murdered people.”

But Jones had something police and prosecutors wanted. His ties to other violent people made him a potential resource to detectives trying to close hard-to-solve homicide cases.

So when Jones was arrested in Seattle, where he’d fled because of the murder charges, he met with Cincinnati Police Detective John Horn, who specialized in cold cases. He told the detective he could provide information about unsolved homicides.

“He talked about many different cases,” Horn said.

In return, Jones wanted a deal.

'You are going to get a benefit'

Not long after he returned from Seattle, in December 2008, Jones signed his first cooperation agreement with Hamilton County prosecutors.

The deal, which remained confidential until a judge unsealed it last year, required Jones to “testify truthfully, completely, and accurately in any legal proceeding” and said he must tell authorities whatever he knew about the Grimmie Network.

On the day Jones signed the deal, prosecutors dropped one of the murder charges against him and reduced the other to involuntary manslaughter. Common Pleas Judge Beth Myers then sentenced him to four years in prison, far less than the 20 years to life he would have faced with a murder conviction.

After making the deal with Jones, Powers said, prosecutors didn’t just take him at his word. She said they tried to corroborate the information he provided through other sources and found he knew things about cases that had not been made public.

She said prosecutors never lost sight of who they were dealing with. “Jones was a career criminal who was clearly motivated by a self-serving desire to reduce the amount of time he was to spend incarcerated,” Powers said.

Jones wasn’t satisfied with his first agreement with prosecutors. He wanted a better deal, and he did a lot of talking over the next 18 months in hopes of getting one.

“He’s playing a game,” said Eric Eckes, a lawyer who represents Marcus Sapp, one of the men Jones accused of murder after signing his cooperation agreement. “The rules are, keep pointing at the people that the government thinks did it. As long as your story matches their story, then you are going to get a benefit.”

Because the deal was confidential, defense attorneys, judges and juries in future cases wouldn’t know its terms. They also wouldn’t know that if Jones went back on the deal, all the original charges, including a possible life sentence, could be reinstated.

Of the 12 homicide cases Jones cooperated on, The Enquirer found, he testified in court about at least five. Each time, Jones said he’d been promised nothing in exchange for his testimony.

According to his written plea deal, that was true. Because the agreement didn’t identify specific cases, Jones could say his testimony in those cases wasn’t connected to his plea deal.

Horn, who is now retired, said that’s a common arrangement. “You haven’t done anything for me until, you know, you do something for me,” Horn said. “There’s never been any promises made.”

But defense attorneys say prosecutors knew which cases Jones would help them with and that claiming otherwise in court was a convenient and disingenuous sleight of hand.

One of those cases was Marcus Sapp’s.

Prosecutors said Sapp, who had previous drug-related convictions, killed Andrew Cunningham in 2008 and two other men, Todd Oliver and Robert Lane, in 2007. The crimes were similar: Two men armed with assault rifles broke into homes, then robbed and shot the occupants.

The evidence against Sapp, the only person charged, included testimony from Cunningham’s roommate, who identified Sapp as one of the shooters, and from Jones, who claimed Sapp bragged about the murders to him on the phone.

At Sapp’s trial in May 2010, defense attorney Thomas Koustmer portrayed Jones as a jailhouse snitch who lied about Sapp to get his plea deal. But Jones denied it.

“I don’t get anything from this case,” he told jurors.

The jury acquitted Sapp of killing Oliver and Lane but convicted him of killing Cunningham. Judge Luebbers sentenced Sapp to life in prison.

Two months later, Jones got a new plea deal and walked out of jail a free man. To Sapp’s lawyers, it sure looked like Jones got something for testifying.

“I have never, ever seen anything quite like this case,” said Martin Pinales, one of the lawyers who convinced Luebbers last year that Sapp deserved a new trial after more than a decade in prison.

After a 'favorable resolution,' problems arise

Jones got his new, improved plea deal after a brief hearing before Judge Myers in July 2010.

Assistant Prosecutor David Prem, who also prosecuted Sapp, said Jones had cooperated “on something that was completely unanticipated” and that Horn, the detective, recommended a further reduction in his sentence.

The new deal, which Myers approved, reduced Jones’ prison time from four years to two, allowing him to go free days after the hearing. “Mr. Jones obviously is getting a resolution here that is obviously something that’s very favorable,” Prem told the judge.

What did Jones do to earn the better deal? Neither prosecutors nor Jones’ lawyer, Perry Ancona, would say.

But court records indicate Jones did more in the months before his new deal than testify against Sapp and offer himself up as an informant in other cases. He also tried to recruit inmates at the Justice Center to cooperate with police and prosecutors.

In the letter he wrote in jail in 2010, Jones urged fellow inmate Donte Jones to talk to Horn and Prem, saying he had information about Sapp that could help him get a good plea deal.

“I will see you face to face once Sapp goes to trial. And I’ll tell you more then,” Quincy Jones wrote. “I got s--- you can use.”

While that recruitment effort apparently failed, another inmate, Gerald Wilson, said he did talk to Horn at Jones’ urging about a murder case in Butler County. With encouragement from Jones, Wilson said, he told Horn he’d heard Calvin McKelton admit to the murder.

But Wilson recanted when he testified at McKelton’s murder trial in October 2010. He said Jones gave him details about the case, which he’d passed along to Horn as though it was his own information.

“He ran down what he wanted me to say to Detective Horn so they could get Calvin indicted,” Wilson testified. “But I ain’t about to sit here and lie.”

According to Wilson, Jones believed recruiting a witness for prosecutors would help him get “an early release.” Horn did not respond to questions about Wilson or McKelton.

The jury convicted McKelton despite Wilson’s recantation, but his claim that Jones asked him to lie wouldn’t be the last challenge to Jones’ credibility. More questions about Jones emerged a decade later, this time in the Marcus Sapp case.

Eckes said police investigative notes show Jones changed his story about how he knew Sapp was involved, first saying he’d heard about it “on the street” and later saying Sapp called him personally to confess.

Sapp declined an interview, but Eckes questioned why Jones wouldn’t have mentioned the confession at the outset, if the claim were true. And he said the notion that Sapp would confess to Jones under any circumstances was absurd because the two men couldn’t stand each other.

“I don’t even know how you convince yourself that Quincy is actually telling the truth that Marcus confessed to him,” Eckes said.

Additionally, Sapp’s appellate lawyers learned that the only eyewitness, Cunningham’s roommate, had identified another man as the shooter from a photo array before picking Sapp, something prosecutors didn’t disclose before the trial.

Sapp is free now, awaiting his new trial, and Jones again is a central figure in the case. This time, though, Jones won’t be on the stand testifying against Sapp.

Two years after he got his new plea deal, on Sept. 29, 2012, someone shot Jones once in the chest as he walked down Euclid Avenue in Cincinnati, killing him. His homicide still is unsolved, but at a court hearing last year, Oswall, the assistant prosecutor, said authorities believe they know the motive.

“He was murdered in the street for being a snitch,” she said.

An informant blames a neighbor

Like Jones, Marcus “Tennessee” Fleetwood worked as an informant before becoming a star witness in a Cincinnati homicide case.

And, like Jones, Fleetwood’s involvement began after a conversation with Detective Horn.

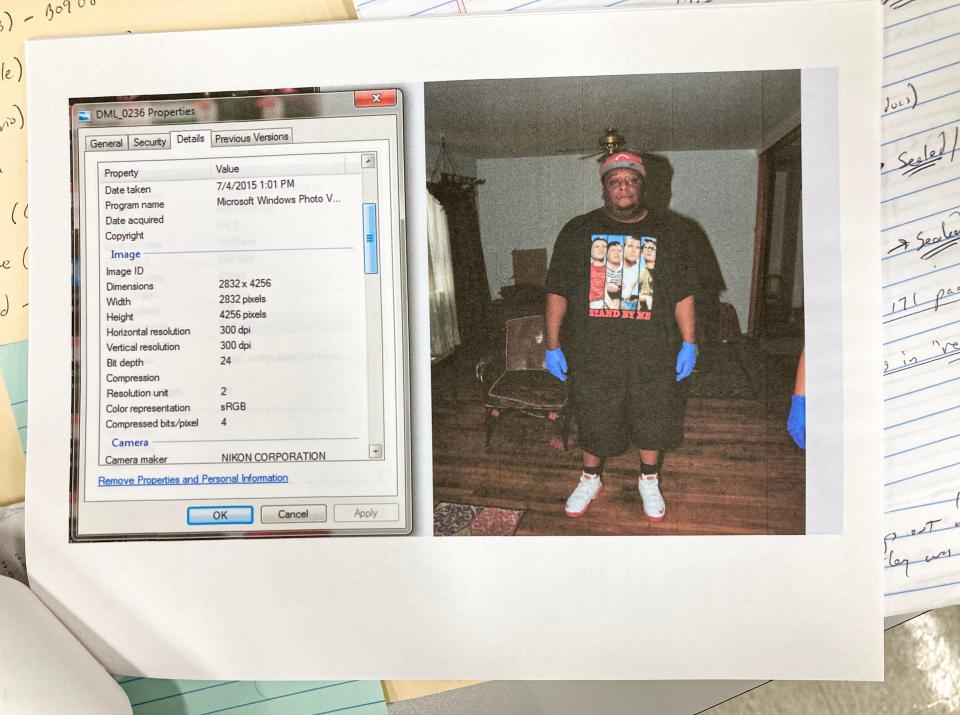

The victim this time was Tammy Wiley, a 54-year-old woman with stage 4 cancer. Police found her body July 4, 2016, in her apartment on Section Road, with duct tape wrapped around her head.

Fleetwood, who sold drugs out of Wiley’s apartment, would later say he discovered her body before police arrived but left because he feared they’d blame him for her death.

He returned to the apartment, however, after Horn called his cell phone and told him to come back to help homicide detectives. Fleetwood said Horn had his number because he’d previously worked with the detective as an informant.

He told police at the time that he and Horn had “a lot of s--- going on.”

Horn wouldn’t discuss his relationship with Fleetwood, other than to say he knew him and that detectives at the scene asked him to make the call.

After arriving at the apartment, Fleetwood was permitted to enter the crime scene. He was photographed there wearing protective gloves and a T-shirt bearing an image from the 1986 movie “Stand By Me.”

At some point, he told police he knew who killed Wiley: Her upstairs neighbor and the building’s part-time handyman, Kayle Taylor.

Two years later, Fleetwood testified for the prosecution at Taylor’s trial. He said he stopped by Wiley’s apartment the evening of July 3 to bring her food, but he said Taylor intercepted him in the parking lot and told him police took her to a hospital because she’d been behaving erratically on drugs.

He said Taylor must have lied to him to keep him out of Wiley’s apartment after he killed her.

Taylor said that encounter never happened. He said he’d spent the weekend before Wiley’s body was found either working or hanging out with his kids and girlfriend. He told The Enquirer his interactions with Wiley consisted mostly of him calling police to complain about noise coming from her apartment.

“She was annoying,” he said, “but I ain’t gonna hurt her.”

Taylor said Fleetwood frequently came and went from Wiley’s apartment and he suspected he was dealing drugs. “I never talked to that guy,” he said.

Aside from Fleetwood’s testimony, the evidence tying Taylor to the killing was a small pile of random items – a mostly-depleted roll of duct tape, a Pringles can of loose change and a few bottles of cologne – found immediately inside of Taylor’s apartment door.

Prosecutors said Fleetwood told police those items had been pilfered from Wiley’s apartment. Taylor said that wasn’t true.

A better suspect than a witness?

Taylor’s lawyers said Fleetwood should have been treated as a suspect, not a witness. That’s because Fleetwood was an admitted drug dealer and Wiley died of some combination of a fentanyl overdose and asphyxiation caused by the duct tape.

“The drug dealer who deals drugs out of her apartment, and therefore puts her at risk and provides her with drugs, is much more likely to be a culprit,” said John Kennedy, one of Taylor’s lawyers.

Kennedy and his partner on the case, Jay Clark, said Fleetwood’s previous work as an informant gave him unearned credibility with police. By implicating Taylor, they say, Fleetwood might have gotten away with murder.

Kennedy said physical evidence gathered at the scene also implicates Fleetwood, who could not be reached to comment. In a front closet inside of Wiley’s apartment, police found a piece of duct tape containing head hairs consistent with Wiley’s, as well as fibers consistent with the clothes she’d been wearing when she died.

The tape was found next to a piece of tissue paper containing fecal matter – and a fingerprint that forensic analysts said belonged to Fleetwood.

But the defense team didn’t know all that before Taylor’s 2018 trial. Despite filing the standard requests for discovery from the prosecutor’s office, Kennedy said, several items were initially withheld – including cell phone records and text messages.

Kennedy and Clark didn’t learn until the trial that police, who’d previously said Wiley’s phone was inoperable, had retrieved text messages months earlier that showed Wiley asked Fleetwood for drugs just before she overdosed.

The defense lawyers were furious. At one point, Clark sent an email accusing Assistant Prosecutor Jeffrey Heile of withholding the evidence, calling him “a dishonest asshole.” Prosecutors said they did nothing wrong and that defense lawyers could’ve hired their own expert to examine the phone.

Taylor’s lawyers asked for a mistrial, but the judge denied the request. Then Kennedy and Clark did something neither had done before. They said they could not effectively represent their client because of the withheld evidence.

On that basis, Judge Steven Martin granted a mistrial.

Taylor could have been tried again, but the new evidence weakened the case against him. Prosecutors offered him a deal: If he pleaded guilty to the lesser charge of involuntary manslaughter, he would be sentenced to probation and would go free.

Taylor, who had spent four years in jail awaiting his first trial, said he agreed to the plea not because he was guilty but because he wanted to end the ordeal. He didn’t trust the system, he said, and needed to get home to his kids and his girlfriend, who was having health problems.

He said he’d already missed too many milestones. “My son riding his bike. My daughter growing up,” Taylor said. “When I first came home, my daughter didn’t even know how to really feel. She’s so used to seeing me behind glass.”

“I missed out on time I’ll never get back,” he said. “That time is gone.”

Hearing confessions through air vents

Informants claim to get their information in a variety of ways. But defense attorneys say few scenarios are as unlikely as the one claimed by Robert “Bobby” Taylor – no relation to Kayle – who testified in 2009 against two men charged with murder.

Taylor, locked up at the Justice Center on a homicide charge of his own, said he overheard the men talking about the crime through the jail’s air vents.

Taylor, then 19, became an informant after going to jail in August 2007 on charges of killing 16-year-old Kendall Dudley, who was stabbed to death in a street fight involving several people. The judge raised Taylor’s bond to $250,000 after he exploded in anger in court, screaming “F--- you all!”

At the Justice Center, Taylor encountered David Johnson and Marty Levingston, who were charged in the shooting death of 19-year-old Michael Grace in December 2007.

Police said Grace, who died in a Mount Airy parking lot, belonged to a Cincinnati gang known as the Northside Taliband, while Johnson and Levingston, both 23, belonged to a rival gang called the Hawaiian Terrace Bloods.

Two witnesses, including one who was with Grace the night of the shooting, identified Johnson as one of the assailants. The evidence against Levingston was shakier, because one witness did not identify him and the other later said she had doubts about her initial identification.

Levingston told The Enquirer he sometimes dealt drugs in Hawaiian Terrace but was at his parents’ house in Western Hills when Grace was shot. He said he turned down a plea deal from prosecutors because he was innocent.

He said that’s where Robert Taylor came in.

Taylor claimed at Levingston and Johnson’s trials in 2009 that Levingston confessed to him and that he later listened through the vents as the two men talked about the shooting. Jail records provided by Greg Cohen, Johnson’s initial defense lawyer, showed the three men were on separate floors, with Johnson beneath Levingston, who in turn was beneath Taylor.

Prosecutors said in court filings that “inmates could speak through vents or between nearby cells,” but floor plans show Taylor’s cell not only was on a different floor, it also was behind a wall of concrete and steel separating him from the other two men.

“It’s not possible,” said Cohen, who called the jail’s facilities maintenance manager as a witness to refute Taylor’s claim.

Levingston said inmates did sometimes use the vents to talk, but he said his cell didn’t share a vent with Taylor’s. He said he never talked to Taylor – through the vents or otherwise – because Taylor had a reputation for using any information he could against other inmates.

“I knew he was a snake,” Levingston said.

Cohen, who described Taylor in court as a “snitch rat bastard,” said Taylor got most of his information by scouring listings in the Court Index, a daily publication of court cases, and then asking other inmates for details that he could later claim he learned on his own.

In March 2008, Taylor cut a plea deal with prosecutors, who dropped the murder charges against him and let him plead guilty to the lesser charge of involuntary manslaughter.

Taylor’s sentencing, however, was delayed for more than a year, until after juries convicted both Levingston and Johnson of murder. Taylor explained the reason for the delay when he was questioned about it at Levingston’s trial.

“If your testimony satisfies the prosecutor, it’s your hope that you’re going to get some leniency in your sentence. Is that correct?” asked Levingston’s lawyer, Hal Arenstein.

“That’s right,” Taylor said.

Months later, his hope was realized. On May 22, 2009, after both Levingston and Johnson had been sentenced to life in prison, Taylor received a five-year sentence for his role in Dudley’s death.

Trying to 'jump' on more cases

Caster, the lawyer with the Ohio Innocence Project, took up Levingston’s case on appeal, arguing the evidence against him hinged on an unreliable witness and Taylor, a man who admitted to informing on four different homicide suspects in hopes of getting leniency.

Taylor didn’t always get his facts right. He claimed, for example, that Levingston told him he’d shot Grace in the head, when, in fact, he’d been shot in the chest and back.

But Taylor, who could not be reached to comment, knew enough to convince prosecutors to put him on the stand. Another informant, Michael Hubbard, later said that was a mistake.

In an October 2009 affidavit, Hubbard said he connected with Taylor in jail while they awaited trial in separate murder cases. Neither wanted to spend the rest of their lives in prison, Hubbard said, so Taylor suggested they “jump on somebody’s case” in hopes of pleading to lesser charges in their own.

Hubbard said in his affidavit that he and Taylor learned as much as they could about other cases through hearsay and media reports. He said they then fabricated additional details to feed police and rehearsed their testimony together.

Hubbard was skeptical of the plan at first, he said, but soon detectives were asking to speak with him at Taylor’s behest.

“That’s when I began to think, ‘Hey, this just might work,’” he wrote. “I am no saint but Robert Taylor would ‘jump on anyone’s Case’ to free himself.”

Levingston said Taylor wasn’t alone. He said several Justice Center inmates, including Quincy Jones, who was there at the same time, wanted to trade information about other cases for leniency in their own.

“They had a little ring down there,” Levingston told The Enquirer. “They was, like, jumping on everybody’s cases.”

Prosecutors argued in court filings that the information Taylor gleaned at the Justice Center was reliable, and that Hubbard’s change of heart was “highly questionable.”

Johnson lost his bid for a new trial. But last year, more than a decade after he went to prison, Judge Wende Cross granted Levingston a new trial.

Prosecutors agreed on one condition: that Levingston plead guilty to involuntary manslaughter and be sentenced to the prison time he’d already served. Powers said prosecutors believed Levingston was guilty but that trying the case after so many years would be “extraordinarily difficult.”

Levingston said he took the plea because he saw no other way to get back home to his family, including his four children. He’s been free since February 2023.

Caster said he and the team from the Ohio Innocence Project are “still convinced that Marty is innocent.” Cohen, Johnson’s lawyer, said he’s also certain Levingston had nothing to do with Grace’s slaying.

“There were two people charged in that case. I represented one of them,” Cohen said. “I can tell you that based on knowledge that I have, Marty Levingston was nowhere near that homicide.”

'He couldn't have seen what he said he saw'

Informant testimony carries risks not just for defendants but also for the prosecutors who put them on the stand.

Sometimes cooperating witnesses change their stories, as Hubbard did months after his testimony, and sometimes they make critical errors on the stand, raising questions in the minds of jurors and judges about their credibility.

When that happens, cases can fall apart fast.

One such case was Rashid Lattimore’s murder trial in 2013. After struggling for years to solve the September 2007 shooting death of Gary Johnson, prosecutors built a case against Lattimore with two cooperating witnesses who claimed to have seen him do it.

One of them, Quincy Richardson, gave Cincinnati police a statement saying Lattimore, who was 20 at the time, fired several shots at Johnson during an encounter on Ridgeway Avenue just after nightfall. The other, Charles Black, told detectives he also witnessed Lattimore fire the shots.

But on the eve of the trial, Richardson and Black refused to testify about what they’d told police. Prosecutors suggested to Judge Charles Kubicki they may have been threatened.

“The two eyewitnesses we have, what they’ve done is they’ve refused to testify on direct and actually give evidence to the jury about what they observed,” Assistant Prosecutor Brian Goodyear told the judge.

Things got worse for the prosecution when Lattimore’s attorney, Mary Jill Donovan, did some digging. A quick check of prison records revealed that Black couldn’t have witnessed the shooting on Ridgeway in September 2007 because he was in prison at the time.

Police and prosecutors missed that detail when they questioned him.

The next day, Kubicki met with lawyers for both sides and summed up the problem: “He had to have been locked up,” Kubicki said of Black. “So he couldn’t have seen what he said he saw.”

Kubicki then did something that rarely happens in Hamilton County murder trials. He granted Donovan’s request to dismiss the case because of insufficient evidence.

In an exchange of messages from prison with The Enquirer, Black acknowledged he was in prison when he’d claimed to be a witness. He said he’d been offered a deal if he testified against Lattimore.

“The police came and asked me when I was locked up and offered me time off my case if I did,” Black said.

He blamed his discredited statement for the severity of the 55-year sentence he received three months after Lattimore’s trial.

Instead of leniency, Black said, “that case got me more time.”

[ Get daily news, in-depth investigations and more delivered straight to your inbox. Consider signing up for an Enquirer newsletter. ]

Using informants is risky. Could transparency prevent mistakes?

How do informants with credibility problems, such as Black, end up playing such crucial roles in a prosecution’s case?

“They use them because they need them,” said Clyde Bennett, a Cincinnati lawyer who frequently defends homicide suspects.

Bennett said prosecutors know the risks associated with informant testimony, and they know jurors might be skeptical of someone with something to gain from cooperating. But he said they put them on the stand anyway if they think their other evidence is lackluster.

He said that happened last year when he defended G’Quan Palmer, whom prosecutors accused of fatally shooting Vincent McGrady, 57, on Gilsey Avenue in West Price Hill in October 2020.

Melvin Jackson, then 42, was a crucial prosecution witness because he named Palmer as the man who pulled the trigger. He did so, however, after police caught him picking up shell casings on the street, prompting them to arrest him for obstructing justice.

Bennett said he couldn’t prove it, but he suspected prosecutors used the charges against Jackson to secure his cooperation in their case against Palmer. Prosecutors said they neither threatened Jackson nor promised him anything in return for testifying.

Whatever happened before he took the stand, Jackson’s testimony did not go as planned. He changed his story several times. He also claimed that Palmer intimidated him and that police threatened to charge him with the murder if he didn’t testify against Palmer.

When the jury acquitted Palmer, the defense and prosecution agreed Jackson’s testimony was a big reason why. It also was a reminder of the risks, for both sides, when informants take the stand.

But prosecutors and police say informants remain an essential part of their work, especially in a time when witnesses who have nothing to gain from cooperating hesitate because they fear retribution.

“In some cases,” Powers said, “the only people left for police and prosecutors to consider as witnesses are individuals with pending criminal matters of their own.”

Horn, the police detective, said juries should be trusted to sort out the relationships between informants and defendants, and to weigh how much a plea deal might influence testimony.

“Do they want something out of it? Almost always, yes,” Horn said of informants. “I think a reasonable jury would understand that that person up there is facing a serious charge sometimes themselves and that they are doing this for some benefit.”

But what if judges and juries don’t have all the information? What if they don’t know how much informants like Quincy Jones or Robert Taylor stand to gain from testifying, or how much they stand to lose if they don’t?

That’s where the system breaks down, defense attorneys say. That’s when mistakes are made.

Natapoff, the expert in informant testimony, has proposed new laws that would require prosecutors to disclose more details about how they use and reward informants and to participate in pretrial "reliability hearings," which would allow courts to test the credibility of informants before they testify in front of a jury.

She and others also support statewide tracking of jailhouse informants so those who testify in multiple cases can be better monitored. Oklahoma passed such a law in 2020 after judges overturned convictions in four cases involving informants.

Natapoff said more transparency is needed because deals that happen behind closed doors are nearly impossible to track. That, in turn, allows informants free rein to dip in and out of cases, working to find and fabricate information to offer law enforcement in hopes of benefiting themselves.

Natapoff called it “the commodification of guilt.”

“When you turn the criminal system into a market,” she said, “you devalue its legitimacy in everyone’s eyes. You’ve announced to everyone that justice is for sale.”

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Cincinnati homicide cases unravel after deals with informants