Enrollment dropped. Absences soared. How one Arizona school is fighting pandemic learning loss

The son of working-class immigrants from Mexico, Tony Alcala grew up just a few blocks from Galveston Elementary School, near downtown Chandler.

Alcala, 41, is now the principal of the same neighborhood school he attended as a child.

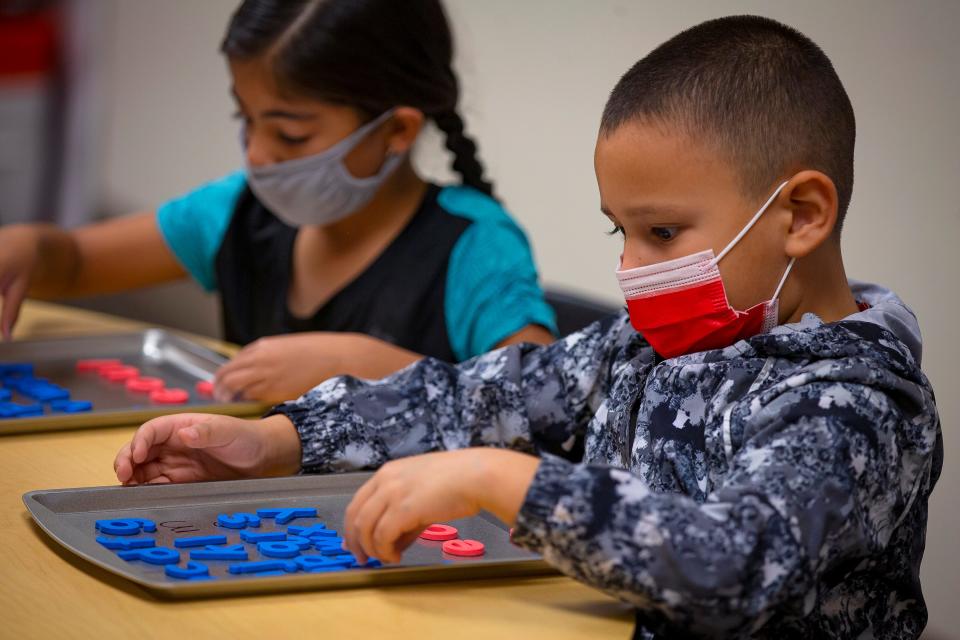

The school illustrates how the COVID-19 pandemic led to decreases in enrollment and increases in chronic absentee rates for students in Arizona, but particularly for low-income Latino students, an analysis of data by The Arizona Republic and WestEd/Helios Education Foundation shows.

Latinos are a large and fast-growing demographic group in Arizona. They make up nearly half of the state's K-12 students and the overwhelming majority of students at Galveston.

The decrease in enrollments and increases in chronic absentee rates have resulted in significant losses in learning for all students, experts say.

But the learning loss has exacerbated an achievement gap among Latinos. The achievement gap has been a public education concern. Now the pandemic has widened the gap even more.

When Alcala was growing up in the neighborhood in the 1990s, his was one of the only Hispanic families.

But the neighborhood where Alcala grew up has changed. The area is now mostly working-class families from Mexico, drawn by the area's affordable housing. The changes mirror demographic shifts that have transformed neighborhoods across Arizona.

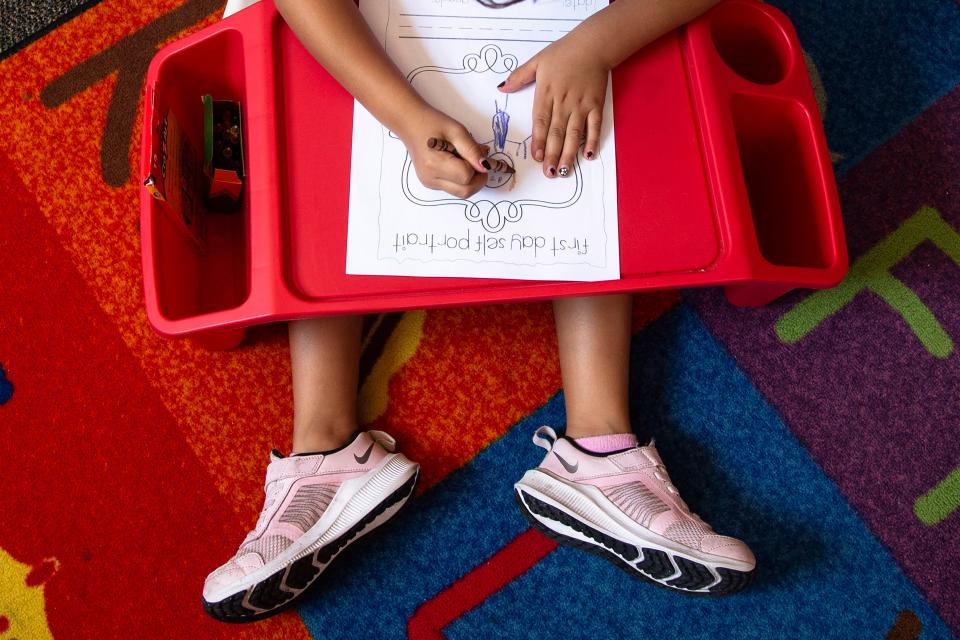

Now, 92% of the approximately 400 students who attend Galveston, grades pre-K to sixth, are Latino. About 87% are considered low-income, according to Arizona Department of Education data.

Many of the parents Alcala has met since he became principal in 2021 work at hotels, restaurants, in construction, landscaping, as house painters and in air-conditioning repair. All jobs that put them at greater risk of exposure to COVID-19.

Missed an entire year of school

Last July, Alcala said, just days before the first day of school, the Latina mother of a former Galveston student visited him in his office. Alcala had just started as principal at Galveston on July 1, 2021, after spending three years as the principal at Arizona College Preparatory Middle School. That school, which is part of the Chandler Unified School District, predominantly serves white and Asian students from higher income backgrounds.

The parent told Alcala that her daughter, who was about to enter fifth grade, had essentially missed her entire fourth-grade year of school because of the pandemic.

The student's parents, Spanish-speaking immigrants from Mexico, worked in the service industry so couldn't work from home.

The mom told Alcala she disenrolled her daughter at the start of fourth grade and enrolled her in the Chandler Online Academy.

At the time, schools were closed and classes were still being taught remotely throughout Arizona, a practice that began in March 2020 to help prevent the spread of COVID-19.

Language barriers made it difficult for the family to navigate the technical process of enrolling their daughter in the online school, so she was already behind when she started.

She lost interest and stopped attending online school, Alcala said.

"She didn't do anything online," Alcala said. "I remember asking her, why. And she said, 'It was hard. We had trouble getting in. We didn't understand who to call'" for support.

The student is repeating fourth grade. She is just one example of many students who missed a significant amount of school in 2021 and are struggling to make up the learning they lost, Alcala said.

In fall 2020, Galveston lost 33 students, followed by another 80 students in 2021.

Alcala believes many of the students switched to online schools.

Some parents may have postponed enrolling students about to enter kindergarten for a year.

Across Arizona, about 8,900 fewer students enrolled in kindergarten in 2020 compared to 2019, an 11% decline. In fact, kindergarten enrollment decreases amounted to 23% of the overall enrollment drop in 2020, The Republic analysis showed.

Some students from Galveston may have moved to other neighborhoods because of job losses or job changes, Alcala said. He knows of some students who moved to Mexico to be closer to extended family members. He did not know of any students from Galveston who switched to homeschooling.

Alcala said it wasn't just students missing school. COVID-19 swept through the Galveston staff: many teachers got sick. And substitutes were not available to replace them.

Alcala ended up filling in as a substitute for more than 20 days himself.

Alcala also missed five days in January because of COVID-19.

Before the pandemic, Galveston had a B rating under the state's A through F school grading system.

He fears Galveston's grade is in danger of falling to a D or an F because of the disproportionate amount of learning lost by his students.

He made a comparison to the experiences of more affluent students at Arizona College Preparatory Middle School, where he was principal before Galveston.

When learning switched to online, parents told their children, "OK, we're going to redo the exercise room, buddy, and (turn it into) an office. That's your learning center. We're going to decorate it. I'm going to get you to Costco, pick up a laptop and get you whatever you need. ...

"That's what many students were fortunate enough to have and our students (at Galveston) do not have," Alcala said.

More: How COVID-19 pandemic magnified challenges for Arizona students not proficient in English

Pandemic led to enrollment drops

Enrollment of public school students in Arizona fell by 3% in October 2020, compared with the same month in 2019, according to an analysis of Arizona Department of Education enrollment data. The data includes students enrolled in district schools and charter schools.

The 2020 enrollment decrease came after annual increases of about 1% since 2012, the analysis showed. (A 3% decrease that showed up in 2017 was because of changes in data collection, not an actual decrease, state education officials said.)

The 3% decrease in 2020 enrollment amounted to a loss of nearly 38,500 students out of about 1.1 million.

The 2020 enrollment enrollment may partially be explained by a greater number of students enrolling for only a part of the school year, either in regular schools or in online schools, said Anabel Aportela, an educational consultant.

Arizona Department of Education data shows the number of students in Arizona enrolled in online schools jumped 50%, from 80,000 in the 2019-2020 school year to about 121,000 in the 2020-2021 school year.

The 49,000 full-time equivalent online enrollments added up to 121,000 actual students, the data shows.

That means a significant number of students were only enrolled in online schools for part of that school year, Aportela said. Some may have enrolled in regular schools for the other part. Others may have missed part of the year entirely.

"If there's nothing in the place of going to school, then you've got learning loss. That's lost time on task in a classroom," she said.

More: His friends chose higher-paying jobs. He chose teaching and helping kids

White students overrepresented

White students were overrepresented in the 2020 enrollment drop, The Republic analysis showed.

White students make up about 37% of the state's K-12 student population. But they made up 56% of the 2020 enrollment decrease, the analysis shows.

Experts say it's difficult to explain why white students were overrepresented because the state does not keep data on homeschool or private school enrollment.

Schools with higher rates of poverty have higher concentrations of Latino students, while schools with lower rates of poverty have higher concentrations of white students, according to Aportela's analysis of state education data.

That suggests white students may have had more resources and opportunities to transfer from public schools to other educational alternatives, like homeschooling and private schools.

"I think that that is happening more than pre-pandemic," Aportela said.

Homeschool enrollments are tracked at the county level.

Homeschool enrollment in Maricopa County, the state's most populous county, jumped 30% in 2020 from the previous year to 19,125, according to Maricopa County School Superintendent data. Homeschool enrollment increased another 6% in 2021, the data shows.

Latinos made up 45% of enrollment drop

The Republic analysis showed that Hispanic students made up about 45% of the 2020 enrollment drop.

That's on par with the 46% share Latinos make up of the overall K-12 student population in Arizona.

The number represents a significant decrease in Latino enrollment at a time when Latinos are the largest racial or ethnic group in Arizona yet academically lag behind white students, said Stephanie Parra, executive director of Arizona Latino Leaders in Education, a nonprofit focused on raising academic achievement for Latino students.

"It just really speaks to the importance of making sure that students get resources and supports that they need to get caught up, because a drop like that could have a real long-term impact on the educational attainment of an entire community," Parra said.

There is qualitative data that many older Latino students disenrolled because they had to stay home to care for younger siblings while parents worked in essential jobs that did not allow them to work from home, said Melissa Castillo. She is the Arizona Department of Education's associate superintendent for equity, diversity and inclusion.

Many older Latino students were forced to leave school to work after parents lost jobs or lost income during the pandemic, which disproportionately hit Latino communities and other communities of color, she said.

Some of the enrollment drop was fueled by Latinos moving from Arizona to other states because of job disruptions, she said.

"They're also a very mobile group," Castillo said.

Chronic absentee rates increased

At Galveston Elementary School, Alcala has seen an increase in students missing school.

The daily absentee rate jumped from about 7% in January 2019 to about 16% in January of this year, Alcala said. That amounts to about 36 more students missing school per day.

The increase in absences is because of students getting sick with COVID-19. But more parents are choosing to keep students home when sick with colds or other mild illness out of an abundance of caution, he said.

Galveston is not alone.

School absences increased at K-8 schools throughout Arizona during the pandemic, according to a study of state education department data by WestEd/Helios Education Foundation, two nonprofit groups.

Before the pandemic, absent students in grades K-8 in Arizona missed two days of school on average. The average number increased to 2.5-3 during the 2020-2021 school year, the study said.

"If you are missing additional instructional time, then obviously you are going to fall behind," said Paul Perrault, one of the study's authors. He is senior vice president of community impact and learning at Helios.

Chronic absenteeism, defined as students who miss 18 or more days at a single school, or 10% of the school year, also increased after the pandemic, the study showed.

In May 2021, 22% of all K-8 students in Arizona were chronically absent. That was up 8 percentage points compared with prepandemic May 2019. That amounts to about 52,000 more chronically absent students.

"So the story is that even when people were back in school, there are a lot of kids who are still missing a lot of school," Perrault said.

The study found that chronic absentee rates for white, Latino and Black seventh grade students were similar before the pandemic. After the pandemic, chronic absentee rates increased for all groups, but were steepest among Latino, Black and Native American seventh grade students, the study showed.

Chronic absentee rates rose the highest among Native American seventh graders, and lowest among Asian students.

Data shows that Latino students are more likely to attend schools with higher shares of economically disadvantaged students, Perrault noted.

The study found that chronic absentee rates among economically disadvantaged students increased far more than for noneconomically disadvantaged students. That suggests the higher increases in chronic absentee rates among Latino students, and other students of color, is tied to higher rates of poverty, he said.

Latino students make up a majority of K-8 students in Arizona, so the impact of an increase in chronic absentee rates on that population is greater.

It means a larger share of students who were already behind overall are at risk of falling further behind, Perrault said.

"This is already a group of students that hasn't done as academically well," he said.

The study was intended to understand which groups of students lost the most amount of learning during the pandemic so that resources can be focused to help them catch up, he said.

"This should be on every educator's mind," Perrault said.

Summer school, tutoring expanded

Arizona has received $4.1 billion in federal stimulus funding, in part to help students make up the learning lost during the pandemic.

The money is distributed by the Arizona Department of Education to individual school districts and schools through funding formulas and grants to implement "evidence-based" programs aimed at "accelerating" learning for students who lost ground due to the pandemic, said Castillo, the associate superintendent.

For more stories that matter, subscribe to azcentral.com.

"We're trying to provide guidance, resources, support in those areas that we know will help us accelerate learning for all of our subgroups," Castillo said, particularly "our Latino students who represent a large number of the student population but continue to be the large number that just is not fairing very well."

Some school districts such as the Dysart Unified School District have used federal stimulus money received through the state to expand summer school programs.

About 42% of Dysart Unified School District's students are Latino.

The district offered a double session of summer school last year by providing additional pay to teachers using the funding, said Shelly Isai, Dysart's director of curriculum, instruction and assessment for high school.

The district added tutoring on Saturdays and before and after school to provide extra support to students, she said.

Three Dysart high schools ranked among the top 10 schools with the largest number of enrollment drops in 2020, according to The Republic's analysis. Valley Vista lost 667 students, a 25% decrease; Willow Canyon lost 597 students, a 30% decrease; and Dysart High School lost 502 students, a 31% decrease.

Isai said the decreases were caused in large part by students who transferred to iSchool, the district's online school. Enrollment at the district's iSchool jumped from 46 in 2019 to 1,725 in 2020, school officials said. Some students transferred to other schools within the district or to schools outside the district, she said.

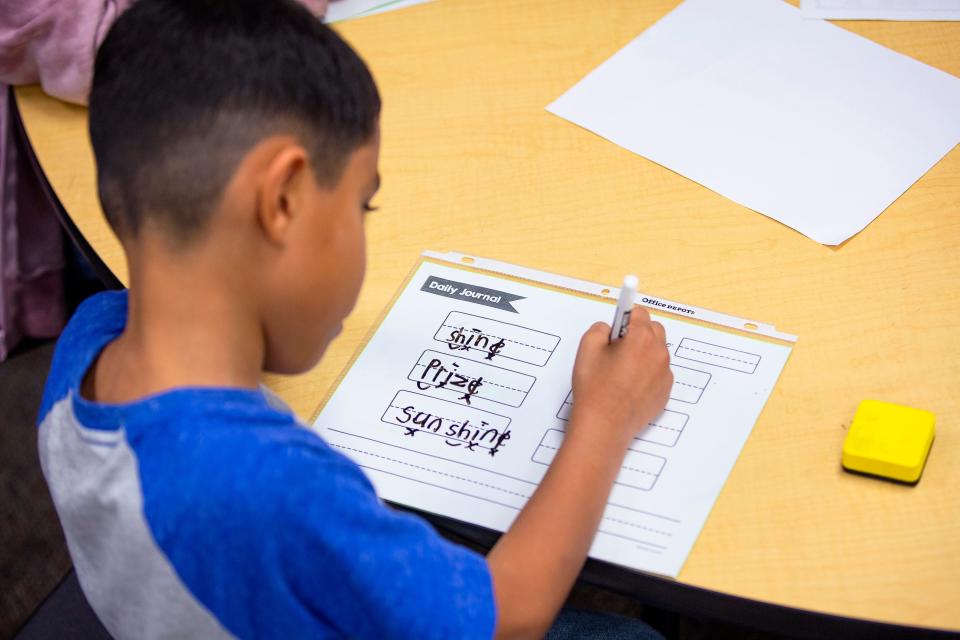

At Galveston, Alcala, the principal, has used federal stimulus funding to pay teachers to provide extra tutoring.

The challenge for teachers, he said, is meeting students where they are academically, which could mean having third grade expectations for a third grade student reading at a first grade level.

Teachers are using test data to determine how much learning individual students lost during the pandemic, Alcala said. He compared the process to an auto mechanic.

"We're not assembly line people (where) I only put in this screw and then it moves on to the next teacher and then they put in this next part," Alcala said. "We really are mechanics, and so with every student we have to look under the hood (and determine) What is the need here? OK, and then let's get to it."

Daniel Gonzalez reported this story while participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 Data Fellowship, which provided training, mentoring, and funding to support this project.

Reach the reporter at daniel.gonzalez@arizonarepublic.com or at 602-444-8312. Follow him on Twitter @azdangonzalez. Support local journalism. Subscribe to azcentral.com today.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Arizona students missed more school during COVID-19 pandemic