How 'staggering' DNA advances could improve our response to climate change

ST. AUGUSTINE, Fla. – Even before sunrise, the tracks of a loggerhead sea turtle on the beach are hard to miss.

Searching for new nests one morning this summer, Mickler's Landing Turtle Patrol volunteer Lucas Meers leaped from an all-terrain vehicle when he spotted a new scalloped trail in the sand.

"False crawl," Meers called out. For an unknown reason, the turtle returned to the sea without digging a nest for her eggs. That meant Meers didn't have to mark a protected area around the nest.

But she probably did leave something behind as she plodded across the beach: a trail of DNA important to University of Florida researchers who are studying these ancient reptiles and the debilitating tumors that plague them.

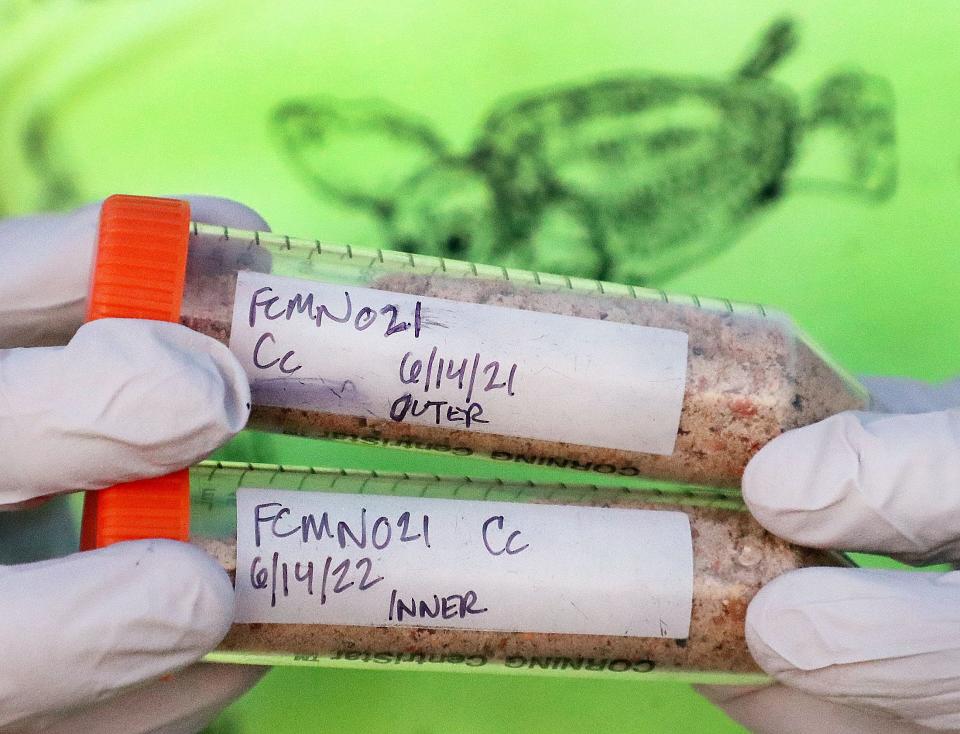

With a quick flick of his wrist, Meers skimmed a vial over the track to collect a sand sample. He'd send it to David Duffy, an assistant professor at the university's Whitney Laboratory for Marine Bioscience. Duffy and his colleagues were the first to collect sea turtle DNA from tracks like these in the sand.

That puts them among a growing cadre of scientists around the globe making rapid-fire developments in using DNA found in soil, water and air to advance wildlife science and conservation. The researchers also hope it will help them race against climate change to understand and protect the world’s still-unexplored special places.

Like the hair cats and dogs leave on living room furniture, wild animals shed small amounts of skin, scat and saliva wherever they go, Duffy said. These trace amounts of environmental DNA, or eDNA, leave trails invisible to the naked eye.

Now researchers can decipher them with the same technologies used to find long-lost relatives and crime suspects.

Think “CSI,” but with ecologists, said Matthew Barnes, associate professor at Texas Tech University. They’re taking vials, laptops and portable genetic sequencing equipment to the world’s highest mountains and most remote jungles.

In the 14 years since the first study about eDNA was published by a pair of biologists studying the American bullfrog’s invasion of wetlands in France, Barnes said it has “emerged as a powerful tool."

“It’s got an element of sci-fi,” he said. “What we’re working toward is the tricorder from "Star Trek," where we could go to a location and point a probe at the lake or the soil and say, 'Here are the organisms that are in this area. It has made it really exciting.'”

Last week, the Wildlife Conservation Society announced that a group of scientists found evidence of 187 taxonomic orders in 20 liters (5.28 gallons) of water collected on Mount Everest at roughly 15,000 to 18,000 feet. The society collaborates on similar projects around the world, including a recent effort that detected whales and dolphins in water samples off New York.

Many others are engaged in similar work, including research on bee pollinators and manatee movements. In the United Kingdom and Denmark this year, two groups of scientists reported they had vacuumed eDNA from the air in zoos, identifying dozens of animals inside and outside the zoos, even in the animals’ food.

At the University of South Florida Sarasota-Manatee, assistant professor Ryan McCleary is preparing to look at what the gut bacteria of an invasive lizard can show about its effect on native species.

The science is “pretty cool,” McCleary said. He and others see important implications for studying hard-to-find species, such as threatened indigo snakes and hundreds of others that share the labyrinth burrows of the gopher tortoise in the southeastern U.S.

“They know you’re there and they’re trying to stay away from you,” McCleary said. “If you can take a soil sample by the hole and see if you’ve got DNA for indigo snakes, then you would have a pretty good idea where to set up your fieldwork and not be wasting your time.”

Tracking biodiversity

The science of eDNA made a splash during the coronavirus pandemic when researchers found they could track COVID-19 outbreaks in municipal wastewater systems. But Tracie Seimon, director of the wildlife society’s molecular lab at the Bronx Zoo, said she would much rather talk about using it to find rare species.

She and others see huge advantages in being able to learn more about rare species without disturbing them.

An author and scientist on the Mount Everest study, Seimon said they “looked at organisms across the entire tree of life … at the whole biodiversity on the highest mountain.”

She and colleagues developed a test to amplify eDNA samples to rapidly detect species, which reduced the size of equipment they needed for this type of work around the world, she said. “You can take the test, throw it in a backpack and go into the field, collect water samples on the spot, then test them and get results in about an hour.”

In Seimon’s view, the strongest applications are for observing ecosystems and monitoring ongoing changes. At Everest, for example, if researchers can collect a baseline inventory, they could return and collect samples over time, she said. “The longer we wait, the less data we’ll have.”

While she and others work to map biodiversity on Mount Everest, many are working with similar goals in tropical rainforests as the forests suffer further alteration and climate change.

Monitoring biodiversity is crucial, said Peter Houlihan, executive vice president, biodiversity and conservation for XPRIZE, a nonprofit organization that hosts public competitions to encourage technological development to benefit humanity.

The XPRIZE Rainforest competition challenged teams to develop autonomous technology for rapid assessment of biodiversity in rainforests. Houlihan said the objective is to find solutions that can survey the greatest expanse of forest.

“We’re definitely seeing a lot of interest in eDNA,” Houlihan said, whether it’s with “overland robotics navigating the understory or aerial robots trying to navigate through or above the canopy.” In June, 15 semifinalists were announced, including four U.S.-based groups. Prizes are set to be awarded in 2024.

Houlihan, a tropical ecologist who specializes in expedition logistics, said things are already changing in the warming world.

Species are moving, shifting in terms of latitude and elevation, he said. Technologies like eDNA will help understand that movement, whether species “are going to higher latitudes or moving north or south.”

One of the trickier aspects to be conquered is figuring out how long the eDNA was there.

“It could be something was there yesterday, a week ago, six weeks or longer," Houlihan said. "We need to understand where species are in space and time to effectively protect them. We need to know where they are and when they are there.”

See photos of DNA science at work: See how scientists are using environmental DNA to learn more about wildlife.

Crossing a bridge to better biology

In St. Augustine, Duffy and his colleagues also collect eDNA from the water where young sea turtles spend part of their lives in northeast Florida's Matanzas River. Like the sand, tests show the water includes DNA shed from the tumors that can blind or kill turtles. Some scientists say warmer waters may be weakening the turtles' immune systems.

Duffy hopes their work will shed light on what causes the tumors to spread and why the tumors afflict some turtles more than others – and may hold a key to unlocking those same questions in human tumors.

As for the use of eDNA, he called the rate of advance "staggering," even though others have considered it "almost an anathema that eDNA could be complementary or even more successful" than traditional fieldwork.

Like Seimon and Houlihan, he acknowledged there's still work to do. "But if that bridge can be crossed, it really does completely revolutionize the way we do biology."

With devices already in development, biologists could track the migration of species in real time as the climate changes, Duffy said. "It's transformative."

Dinah Voyles Pulver covers climate and environmental issues for USA TODAY. She can be reached at dpulver@gannett.com or at @dinahvp on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: 'Staggering' DNA advances could improve response to climate change