The EPA internally raised concerns about Seresto flea collar for years, new records reveal

Even as it assured the public of its safety, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency privately raised concerns for at least six years about the disproportionate number of incidents of harm and death linked to the popular Seresto flea and tick collar, newly released government documents show.

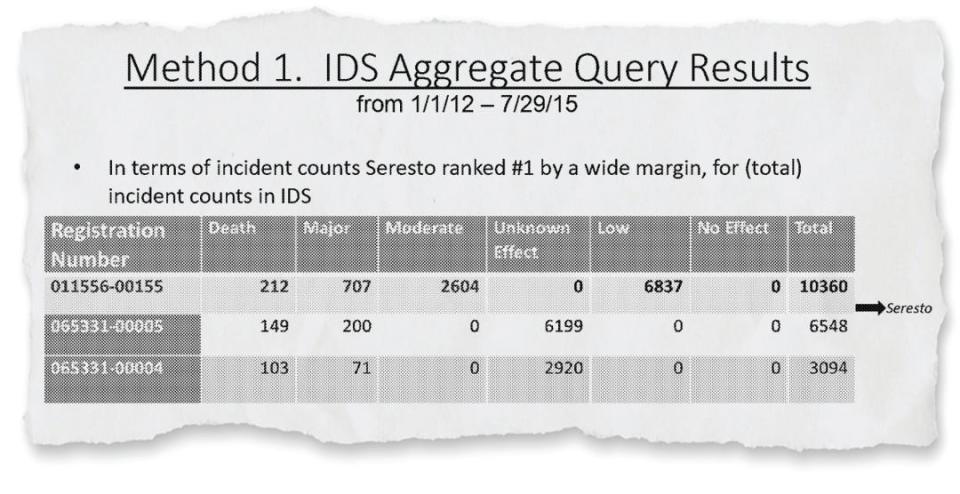

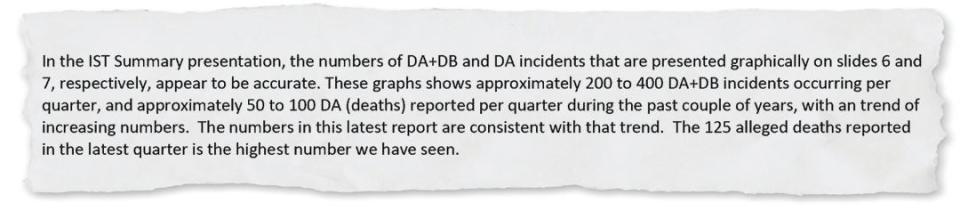

As early as 2015, the EPA said that Seresto’s incident count “ranked #1 by a wide margin” compared to other pet flea and tick products. Three years later, the agency recognized that it would receive reports of 50-100 pet deaths related to Seresto every three months with a “trend of increasing numbers.”

Yet the agency allowed the continued sales of the collar despite numerous deliberations about the reports and continuously meeting with Bayer, the producer of the collar, about the reports. Bayer, which said in its 2019 annual report that it made $300 million on the collar, sold its animal health division, including the collar, to Elanco Animal Health, a former subsidiary of Eli Lilly and Co., for $7.6 billion last year.

Earlier this year, Investigate Midwest and USA TODAY found that the EPA has received at least 1,698 reports of pet deaths and more than 75,000 incident reports of pet harm related to the Seresto collar since it was approved in 2012. Following that story, the U.S. House Committee on Oversight launched an investigation into Seresto and asked Elanco to voluntarily recall the products. A number of class action lawsuits have since followed.

In addition, the newly released documents show that the EPA was in contact with Canadian health officials for months in 2016 as Canada considered, and ultimately refused, to let Bayer sell Seresto in that country. The EPA previously told Investigate Midwest and USA TODAY that it had no knowledge of Canada’s decision-making process.

More: Seresto pet collars under EPA review, but the fight over their safety could take years

The documents were obtained through a lawsuit filed against the EPA by the Center for Biological Diversity.

Lori Ann Burd, environmental health program director for the center, said this is an “explosive” set of documents.

“It shows they knew. It shows they did nothing,” Burd said. “If anything, these documents make it worse. They were so well aware of the scope of the problem.”

The EPA said it was not able to immediately provide a comment.

In a statement, Elanco spokeswoman Colleen Dekker said the company has conducted third-party reviews of Seresto and continues to stand by the collar’s safety.

“All data and scientific evaluation used during the product registration process and through Elanco’s robust pharmacovigilance review supports Seresto’s safety profile and efficacy,” Dekker said. “Seresto protects millions of dogs and cats against potentially harmful fleas and ticks, which can transmit dangerous disease and impact pets’ quality of life.”

Dekker said that an analysis by the company determined that 0.3% – or one in 300 – of pets have reported an adverse reaction, and that the existence of a report does not mean that Seresto caused the incident.

“It’s critically important to understand that these raw reports are not an indication of cause and must be further investigated and analyzed to determine if they were actually caused by the product,” Dekker said.

Dekker said an investigation by Elanco found that 12 pets have reportedly died in a manner probably or possibly casually related to the Seresto collar.

“None of these were linked to the active ingredients in Seresto, but instead due to the physical nature of a collar,” Dekker said in an emailed statement.

Bayer did not respond to questions about Seresto, instead issuing an emailed statement.

“Bayer completed its sale of its animal health division to Elanco in August of 2020 and this sale included Seresto flea and tick products. We no longer manufacture or market this product,” the statement said.

The Center for Biological Diversity filed a legal petition in April to revoke Seresto’s registration. The EPA pledged to further investigate and opened a public comment period on the petition in July.

Seresto works by releasing small amounts of two pesticides onto the fur of cats and dogs for months at a time. The pesticides – flumethrin and imidacloprid – are supposed to kill fleas, ticks and other pests but be safe for pets.

But the documents show the EPA has been closely monitoring Seresto for years, receiving and discussing complaints alleging that the pesticides on the collar were killing and injuring pets.

The documents revealed a long, troubling history with Seresto:

The EPA initially rushed the 2012 approval of Seresto so the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention could use the collars to help control Rocky Mountain spotted fever on dogs in Indian Country in Arizona.

In addition to pet owners, veterinarians also had submitted concerns about the collar. One veterinarian in New Jersey, for example, asked if the EPA could help test the collar after a dog had a severe skin reaction. And an EPA employee wrote in 2016 that Seresto was involved in “quite a few incidents reported to NPIC through the vet portal.” The NPIC stands for the National Pesticide Information Center, which tracks pesticide-related incidents.

The EPA did not respond to previous questions this year about whether a comparative analysis had been conducted, but documents show that such an analysis has been conducted numerous times over the years. Those analyses were not available in the documents.

For years, officials at the National Pesticide Information Center forwarded “special interest reports” about Seresto to EPA officials. These reports, which were treated differently than other pesticide products, included numerous cases of pet deaths.

Other reports that were forwarded to EPA staff included the case of a 9-month-old cat that had a severe skin reaction to the collar and that of a dog with a “life-threatening” skin condition after wearing the collar. Two people also reported their own issues after placing the collars on their pets: One person got a skin reaction; another had a breakout of mouth sores.

In another report, a veterinarian said that a 9-year-old Australian shepherd mix was brought to the emergency clinic for vomiting, uncontrolled shaking and uncontrolled urination two days after the collar was applied. The collar was removed at the clinic, but two weeks later, the owner put the collar back on the dog. It had a similar episode and died two days later.

2015: ‘EPA is closely evaluating the reported incidents’

Numerous times over the years, the EPA expressed interest in further investigating and regulating Seresto.

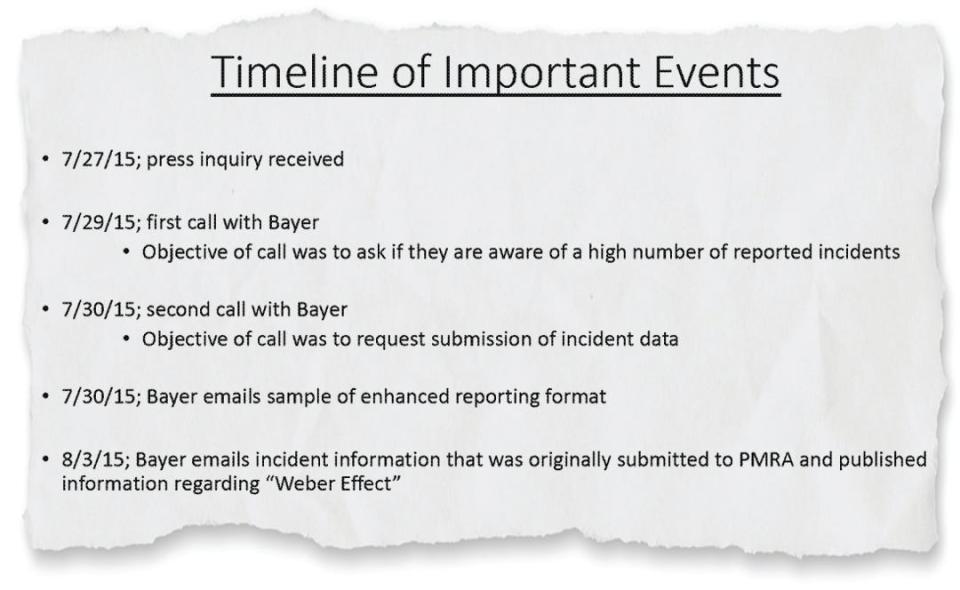

But it appears the agency did so only after getting a press inquiry from WNBC New York in July 2015. The news outlet asked if the EPA was aware of a high number of incidents surrounding Seresto and if there were any ongoing investigations. An investigation launched the same month, according to the documents.

“At this point, EPA is closely evaluating the reported incidents on Seresto to determine whether there is a causal relationship between this product and the incidents reported. If at any time we determine that the collar presents unacceptable risks, we will take action to mitigate those risks or remove the product from the marketplace,” the EPA told WNBC New York.

Two days after the inquiry, the EPA held its first call with Bayer to ask if it was aware of a high number of reported incidents. The next day, the EPA asked Bayer to submit incident data.

On Aug. 3, 2015, Bayer emailed incident data it shared with Canadian regulators, who were at the time considering approving the collar, as well as information regarding the “Weber Effect.” According to the National Institutes of Health, the Weber Effect refers to a pattern of complaints about a new drug peaking in the second year of its being on the market with complaints dropping after that.

However, incident data show that Seresto's adverse incident reports have only increased since 2015. In November 2015, EPA asked Bayer about an increase of incidents between Quarter 2 and Quarter 3.

By December of that year, three divisions of the EPA worked together to brief upper management on Seresto. A Dec. 16, 2015, PowerPoint presentation by the EPA laid out a timeline for the investigation.

In that presentation, the EPA had found that Seresto was “No. 1 by a wide margin” in terms of overall incident reports compared to pet pesticide products, including spot-on treatments. The agency also conducted a comparative analysis of Seresto and other pet products, much of which was redacted in the recently released documents.

‘We need to try to keep ahead’

By 2016, documents show that the EPA was paying close attention to Seresto, particularly as Health Canada, the agency in charge of regulating national health policy, was expressing concerns about registering Seresto.

On April 20, 2016, EPA staff was alerted in a voicemail that Health Canada decided that Seresto should not be registered, based on an analysis of incident data provided by Bayer.

On April 27, 2016, an EPA staff member wrote to a number of EPA employees about needing to stay on top of reports on adverse effects attributed to the collar: “Please share if you see or hear something about Seresto/Flumethrin. We need to try to keep ahead/abreast of the issues surrounding on this case.” She followed it up with a smiley face.

In the following weeks and months, the EPA and Health Canada communicated a number of times, while Bayer worked to convince Health Canada to redo its evaluation of Seresto. In one July 5 email, Bayer lobbyist Doug Spilker outlined how Health Canada should change its analysis.

On June 9, 2016, EPA officials held a meeting with Bayer about Seresto incident data. In a presentation for that meeting, the EPA said it was “working closely with PMRA on analysis” and reviewing specific analyses done by Canadian regulators to determine how likely it was that the collar caused the adverse incidents. Much of the rest of the presentation was redacted. PMRA is Canada’s Pest Management Regulatory Agency.

Eventually, PMRA did share its analysis with the EPA after confirming with Bayer Canada. “Please keep in mind that it should not be shared outside of the EPA,” wrote an employee on July 18, 2016.

That analysis was not included in the newly released documents.

In an Aug. 10, 2016, conference call, Health Canada told the EPA that it would not register Seresto in Canada. “As a result, Bayer withdrew the submission and requested PMRA not share any further documents with EPA,” according to a briefing document.

Despite never having approved Seresto, Health Canada has received more than 1,500 incident reports about the collars, said spokeswoman Anne Genier.

2018 and later

EPA officials continued receiving incident reports involving Seresto for the next five years. And they continued debating what to do about them.

In February 2018, for example, three divisions of the EPA’s Office of Pesticide Programs met “to discuss how to best handle the review of incidents for Seresto. A clear path forward was not decided upon.”

In 2020, an agency scientist said she was tasked with looking at incident reports and taking action to find “supportive actions that may reduce risk and adverse effects toward those particular incidents.”

The EPA also continued to meet with Bayer about the incident reports.

The agency held a July 16, 2019, meeting with Bayer and representatives of SafetyCall International, a company whose website says it provides manufacturers with “adverse event management, regulator reporting, post-market surveillance and consulting.”

A presentation from the meeting shows that the EPA was aware of more than 1,000 pet deaths allegedly related to Seresto, including a sharp rising trend that included about 250 pet deaths in 2016, more than 300 pet deaths in 2017 and more than 400 in 2018.

Just weeks earlier, the EPA received yet another incident concerning Seresto. The incident was then forwarded to at least 19 EPA staff members.

On May 29, 2019, Barbara Merckle put a Seresto collar on her 5-year-old English mastiff, Ivan, just before a breeding session with another mastiff. Within half an hour, Ivan had trouble breathing.

Thinking he was overheating, Merckle hosed down Ivan. When he didn’t improve, she called a veterinarian and was told to administer Benadryl, which Merckle did. Then, Merckle said, she remembered the collar. She removed the collar from Ivan’s neck and washed the area with Dawn dish soap. Eventually Ivan recovered, but he died the next day.

Sarah Crockett, a veterinary assistant who owned the other mastiff, contacted Bayer and the EPA on behalf of Merckle. Crockett, a former police officer, documented the incident but said she was told by Bayer that the collar could not have caused the death.

Crockett contacted the EPA seeking information on how to link the death of the mastiff to the collar, including which tests to do. Amy Mysz, who works at the EPA, told Crockett she communicated with a veterinarian at the National Pesticide Information Center who recommended looking at the liver, kidney, urine and feces, as well as potentially blood levels.

A necropsy done by the Ohio Department of Agriculture found that Ivan was otherwise healthy and moderate to severe congestion of the liver and lung caused by “shock, possibly anaphylactic shock” potentially contributed to the death.

But Mysz – after communicating with several EPA staff members on the response, including one veterinarian – said “he felt that even if this concentration in tissue information was obtained, it would still be difficult to reliably link the use of the collar to the death of the animal.”

Merckle said, for now, she’s not interested in filing a lawsuit because it won’t bring Ivan back. She got the closest thing she could by raising one of the puppies sired by Ivan, a near identical mastiff named Ike.

Merckle said she knows that Seresto caused the death of Ivan, a prize breeding dog that had sired a couple dozen litters. Merckle had paid $2,500 for Ivan a few years earlier and was set to make around $1,500 for each breeding session, in addition to profit from puppies she raised.

Merckle had just purchased a few thousand dollars worth of Seresto collars for her dogs, and she decided to just throw them out. She asked Bayer for a refund and they refused, she said.

“I know that’s what killed him,” Merckle said.

This story is a collaboration between USA TODAY and the Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting. The center is an independent, nonprofit newsroom covering agribusiness, Big Ag and related issues. USA TODAY is funding a fellowship at the center for expanded coverage of agribusiness and its impact on communities.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Seresto flea collar raised concerns at the EPA for years, records show