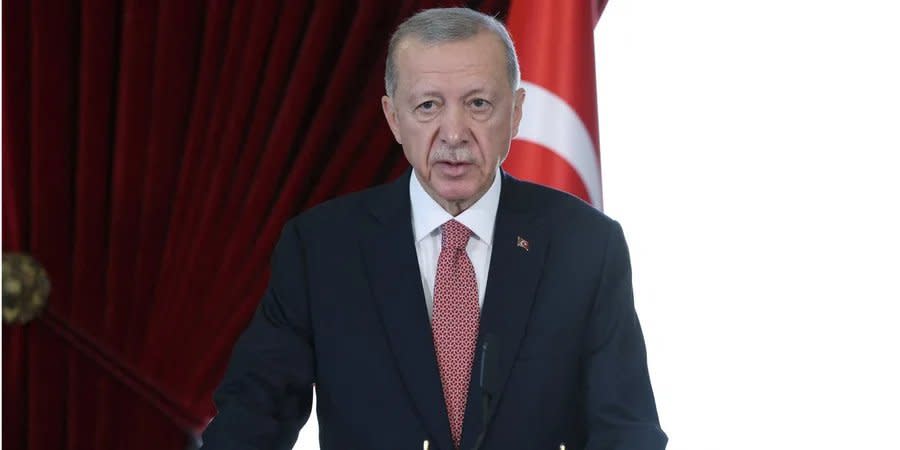

Erdogan’s delicate balancing act

What do Ankara's steps toward Kyiv mean, and is Turkey ready to relinquish its "special relationship" with Moscow?

Since the beginning of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Turkey has chosen to play the role of an impartial arbitrator and mediator, enjoying the trust of both sides. Its policy of delicate balancing, which has occasionally drawn criticism, has proven to be a risky but generally successful strategy. By putting its own interests at the heart of any decision, Ankara has managed to maintain relations with both strategic partners in a state of war. While consistently providing Ukraine with political, diplomatic, and military support, Ankara actively developed economic ties with Russia, often bypassing sanctions and contrary to the common position of NATO member states.

Read also:

Member of Central Election Commission fled to US before invasion, hasn’t returned since

2.4 million Ukrainians remain abroad since start of Russia’s full-scale invasion

Full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine projected to last beyond Biden's first term — Berezovets

This precarious balance shifted to one side or the other at different times, but invariably returned to equilibrium. However, Ankara's recent decisions in favor of Ukraine have led to talk of the Turkish scales finally tipping in Kyiv's favor. But does this mean a fundamental change in Ankara's policy?

Help yourself

Ankara's consistent support for Ukraine's territorial integrity and NATO membership, Zelensky's successful visit to Istanbul and the handover of Azovstal's defenders to Ukraine, the signing of a Memorandum of Cooperation in Strategic Industries, and the intention to build a center for the production and maintenance of Bayraktar UAVs in Ukraine are steps that leave no doubt about the "pro-Ukrainian" nature of Turkey's "neutrality."

Read also: Zelenskyy lands in Ankara to meet with Erdogan

However, these decisions are no less dictated by Ankara's own interests.

Ukraine plays a crucial role in deterring Russia's military power in the Black Sea, which poses a threat to Turkey itself. The creeping occupation of the Black and Azov Seas, obstruction of freedom of navigation and the functioning of logistics chains, militarization, and nuclearization of the Crimean Peninsula threaten to gradually turn the Black Sea into a "Russian lake." This is well understood in Ankara.

Turkey's decision to provide Kyiv with attack drones, when other partners were only considering providing lethal weapons, was not least dictated by the need to prevent the establishment of complete Russian control in the region. Later, this prompted Turkey to provide Ukraine with other systems and means of defense against Russian aggression, which Ankara prefers not to discuss publicly.

Moreover, the confrontation between Turkey and Russia in several regional theaters - from Karabakh and the South Caucasus to Syria and Libya - is forcing Ankara to look for partners to deter the Kremlin's expansion in the immediate vicinity of its borders. Thus, applying the provisions of the Montreux Convention (which restored Turkey's sovereignty over the straits from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean) in the first days of the full-scale invasion, Turkey blocked the straits for Russian warships not only to enter but also to leave the Black Sea, thereby limiting the possibility of logistical support for Russian forces in Syria from the occupied Crimea.

Read also: Russian military forces allegedly raid Wagner bases in Syria, reports Saudi news channel

By strengthening Ukraine's defense capabilities and developing military-technical cooperation with Kyiv, Turkey is also strengthening its own positions in the region. To this should be added the political dividends Ankara receives in relations with the West from its mediation role in the Ukrainian-Russian war, as well as reputational gains in the Global South and economic benefits from the grain initiative.

This in no way diminishes the contribution to our victory of the Turkish Bayraktars, the Kirpi LNG, or the Ukrainian Corvettes currently under construction at the Istanbul docks. Instead, this interdependence of Ankara's and Kyiv's strategic interests emphasizes the almost unlimited possibilities for developing mutually beneficial cooperation. These limitations are now becoming less and less, but they remain.

Crimea, Rome, and copper pipes

The 2023 presidential election, won by Erdogan mainly on the back of harsh anti-Western rhetoric, is now behind us. Local elections in 2024 are ahead, in which the ruling party seeks to regain control of the country's key metropolitan areas, from Istanbul and Ankara to Izmir and Antalya. All this will require a rapid economic recovery and the favor of the opposition, secular, electorate. This means Western investment, which Russia cannot replace, even by pouring billions of dollars into the Turkish economy through the Akkuyu nuclear power plant being built by Rosatom or the relocation of Russian businesses.

Moreover, Russia itself is becoming an increasingly unattractive partner. Although Turkey is not a signatory to the Rome Statute, so it is not obliged to comply with the ICC's decisions, meetings with war criminal Putin are becoming toxic. Erdogan ignores the "concerns" of Western partners, but cares about his international reputation. The Kremlin's war crimes in Ukraine, Russia's withdrawal from the grain initiative, and brutal attacks on Ukrainian port infrastructure, and blatant violations of the rights of Crimean Tatars in occupied Crimea do not add points to Putin's score in the eyes of official Ankara.

Read also: On the Eve of Elections, Erdoğan Invites Putin. What Awaits Turkey? — opinion

The weakening of the Putin regime, demonstrated by Prigozhin's march on Moscow, was another nail in the "special relationship" between the Turkish president and his "dear friend" Putin. Ankara respects the strong and the legitimate.

Erdogan's new cabinet demonstrates that, despite his election rhetoric, he is ready to say goodbye to hardline nationalists and pro-Russian hawks so that moderate and pro-Western professionals can shape the new government's policies. This opens a window of opportunity for Turkey's "return" to the West, which Ukraine can and should take advantage of.

However, turning "towards the West" does not mean "turning your back on Moscow."

Excessive weakening of Russia is still perceived in Ankara as a way to strengthen NATO, which Turkey wants to avoid. In addition, Ankara's fears of Russia's destabilization and disintegration, escalation of direct confrontation between Russia and NATO in the Black Sea, and the Kremlin's nuclear blackmail "red lines" are successfully fueled by Russian propaganda in Turkey. Russian media are still present in the Turkish information space, and Rossotrudnichestvo still enjoys the privileges of a diplomatic mission and opens new "cultural centers" across the country.

Finally, Turkey's economic interests and dependence on Russian hydrocarbons, and now nuclear fuel, keep Ankara firmly within Russia's sphere of influence.

Sworn friends

Russia remains Turkey's primary source of energy and an important economic partner. According to official data, in 2022, Ankara purchased 45% of gas, 40% of coal, and 20% of oil from Russia for its own needs. Turkey's imports of Russian crude increased sharply after the imposition of sanctions, which Turkey did not join. Of course, payment for energy resources, as well as their uninterrupted supply, remains a lever of the Kremlin's political and economic influence on Ankara.

During this period, trade between the two countries more than doubled, reaching a record $68 billion in 2022. Russia confidently holds the lead in terms of Turkish imports and is Turkey's seventh-largest export partner. In January-April 2023 alone, the country increased its exports to Russia by 83%, selling goods worth $3.2 billion (in the same period, Turkish exports to Ukraine amounted to $398 million).

While Turkey is struggling with the economic crisis, Russia remains the leading supplier of tourists, and Russian capital established more than 1,300 companies in Turkey last year, which is 670% more than in 2021.

turning "towards the West" does not mean "turning your back on Moscow."

Grain imports are also worth mentioning. Turkey can meet its needs through its own production. However, maintaining global leadership in flour and pasta exports directly depends on the functioning of the grain initiative and grain supplies from both Ukraine and Russia (Turkey is one of the three primary beneficiaries of the grain initiative after China and Spain).

In addition, Ankara and Moscow share strategic interests. Russia's presence in Syria could potentially create problems for Turkey by provoking new refugee flows. The normalization of Erdogan's relations with Assad, necessary for the return of millions of refugees home, is possible only in multilateral formats involving Russia and Iran.

Finally, Turkey has repeatedly stated its ambitions to become a powerful center of power in the "post-Western world," and this desire to challenge Western dominance and U.S. hegemony also unites the two leaders. For Erdogan, Russia is the door to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, the BRICS, and "Greater Eurasia," even if it goes no further than statements. In addition, contacts with Russia are an opportunity to periodically remind the West that for every undelivered NATO Patriot, there is a Russian S-400.

What to expect next?

Read also:

Turkey, Saudi Arabia in secret talks to repatriate Ukrainian children abducted by Russia – FT

Turkey begins construction of second corvette for Ukrainian Navy

Russia negotiating new ‘grain deal’ with Turkey and Qatar — report

Ankara's next steps will depend not only on the outcome of Erdogan's upcoming meeting with Putin, but also on the dynamics of Turkey's relations with its Western partners and the success of Ukraine's counteroffensive. As a country that remained neutral in World War Two until declaring war on Hitler's Germany on February 23, 1945, Turkey knows how to maintain intrigue.

The domestic political context is also essential. It is clear that Erdogan's new cabinet will focus on strengthening Turkey's regional status, rescuing the economy, and improving ties with the United States and the EU, which remains Turkey's primary export market and trading partner with a trade turnover of nearly $200 billion. All of this, as well as the prospects for Turkish companies to participate in Ukraine's postwar reconstruction, create favorable conditions for strengthening cooperation.

After all, Erdogan is a pragmatic politician. With an unstable Russia on his doorstep and a struggling economy at home, improving relations with Ukraine and the West seems like a better investment in the future than tolerating Russian blackmail.

Read also: Russia negotiating new ‘grain deal’ with Turkey and Qatar — report

However, a miracle will not happen. Turkey's interests require avoiding a sharp deterioration in relations with Russia, and therefore, balancing remains a strategic priority for Ankara, albeit with tactical adjustments to the success of the Armed Forces.

We’re bringing the voice of Ukraine to the world. Support us with a one-time donation, or become a Patron!

Read the original article on The New Voice of Ukraine