How can the Erie region recover? Find new ways to capitalize on natural resources

This is a third in a series of columns by retired Erie engineer William R. Miller exploring possible avenues for growing the region's economy.

The Erie area's more than 100-year reign as a major iron product manufacturing center began with the discovery of major bog iron deposits in the early 1800s along the shores of Presque Isle Bay and other nearby points along the nearby Lake Erie shore. The beginning of the end of that era was when local the deposits began to run out around 1900. However, bog iron is unique among almost all minable minerals in that it is a renewable resource.

Recovering our iron industry and enhancing game lands

Bog iron is formed when springs from deep in the earth that are rich in dissolved iron salts bubble up through bogs which have a certain chemistry and biological composition. In this instance, the soluble iron compounds get chemically converted to insoluble iron compounds which precipitate out as iron rich crystals. Much of the iron used in the America's colonial days was bog iron. Unfortunately, one of the first things the early farmers did was to drain the bogs to make more farmland and the bog iron producing process in that locale stopped.

The same springs, rich in iron, are still bubbling up from deep in the earth. In a natural environment, it takes about 30 years to form minable crystals. It would probably be possible, using the most modern technology, to considerably accelerate the conversion. We would hope to draw on the technical resources of the local colleges and universities. Local funds could probably be supplemented by state and federal grants. It is therefore proposed that a chain of artificial bogs be created near some of these springs to begin rebuilding the iron resources of the area, a sort of "iron farming" operation. These bogs would also be a major draw for waterfowl. Therefore, these bogs could do double duty as state game lands while the crystals are forming.

Incidentally, bog iron typically contains natural silicates that are said to reduce rusting in the final product. Much of the early Griswold ironware, manufactured in Erie, was originally made from bog iron and may have had this desirable attribute.

Mine sand and gravel for a new generation of cement

Many years ago, I and 20 other experienced engineers from different companies, all with many patents in our names, were invited to a brainstorming session in Washington hosted by the U.S. Department of Transportation, the Department of the Interior and several other government agencies. We were asked to find ways to reduce the rate of decay of the highway infrastructure plus other concrete structures like dams and bridges. The group came up with a few suggestions for some incremental improvement but nothing major.

The "gold standard" we all knew would be if we could find a way to heal or at least significantly retard the cracking problem. Human bones are capable of healing cracks. Such cracks are always forming as we stress our skeleton structure but the body has cells that continually fill in and "heal" the crack. This repair is going on all the time without us ever realizing it.

In 2004, I was excited to see that UCLA had designed a plastic that would heal itself, which was certainly encouraging. Then, just a year or so ago, a Dutch company, Basilisk, came out with self-healing concrete.

Thanks to the last Ice Age, plus the inland sea that once covered this area, northwest Pennsylvania has abundant sand and gravel, key elements in cement and concrete. Gravel is one of our region's major exports.

Might it be possible for a local university or company to get a license from this Dutch firm so that we could begin production of self-healing concrete?

More possibilities? Sand and limestone

It is no coincidence that Corning glass, Pittsburgh Plate Glass, Tiffin Glass, and Owens-Corning are all strung along a belt that extends from southern New York to southern Pennsylvania and central Ohio into eastern Illinois. These plants are located where they are because of a belt of a type of sand that is ideally suited for glass manufacture. There would seem to be a good possibility that some of this type sand may crop up in our region. It would be worth a look.

As the last glacier pushed south, grinding most of the strata into sand and gravel, it occasionally hit rock that was too hard for it to pulverize. These slabs of rock were pushed ahead of it until the glacier finally stalled, at the end of the last Ice Age, in the middle of what is now Erie County. An outcropping of this hard blue limestone was found in Franklin Center and, for years, Howard Stone Quarry mined it. It apparently made excellent floor tile, according to the "History of Erie County" by John Elmer Reed.

It stands to reason that there is more of this valuable building stone just below the surface. Perhaps ground penetrating radar could locate new deposits.

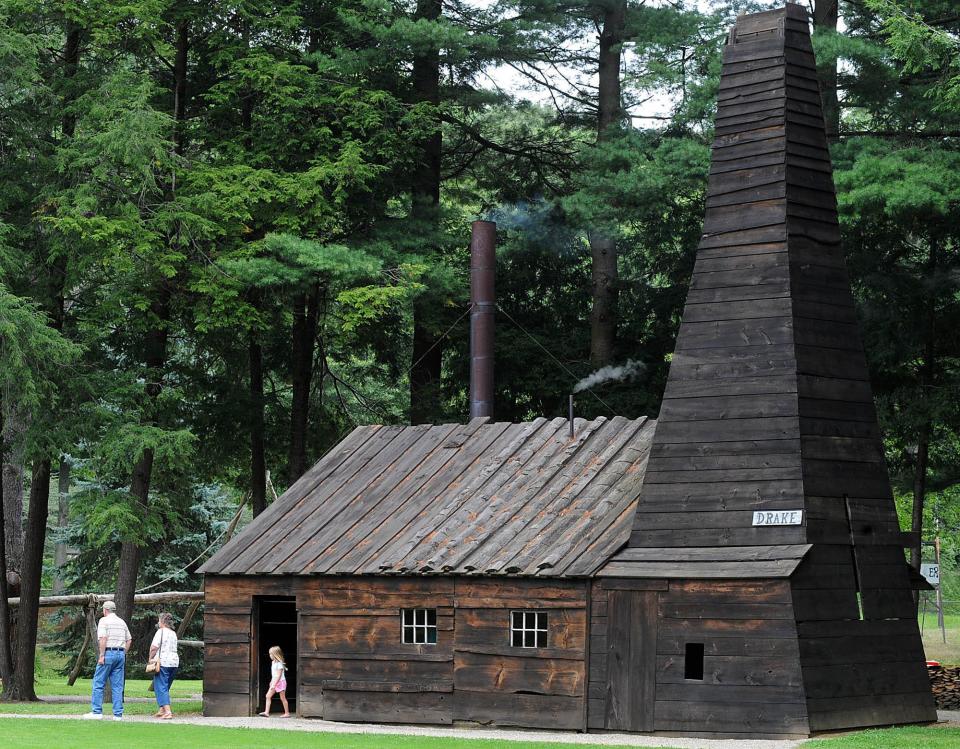

Refocusing the Pennsylvania and New York oil industry

Ninety percent of all the oil in Pennsylvania comes from upper Allegheny in northwestern Pennsylvania and 90% of New York's oil comes from Chautauqua County. Due to the difficulty in extracting this oil, which is trapped in rock rather than sand as it is in Texas, an estimated 67% of the original deposits are still in the ground. Significant improvements have been made in extracting oil from rocky strata with reduced environmental impact.

With all the focus on reducing the burning of hydrocarbon fuels like oil, it might be advisable to take advantage of the unique characteristic of oil in this region to change focus.

Unlike the oil from most of the big, oil-producing states, whose oil is sulphur-based, our local oil is carbon-based. This makes this oil far superior for use as a lubricant. Every piece of moving equipment in the world depends on and will probably always depend on lubricating oils and greases. We should promote and incentivize the manufacture and distribution of Pennsylvania and New York lubricants and move away from wasting our oil, with this unique property, on making diesel fuel and gasoline.

Let's rethink coal energy

One third of the world's electrical energy currently comes from coal-burning power plants. This percentage has not changed much recently, since countries like China and India are adding plants about as fast as the U.S. and European countries are decommissioning theirs. The U.S. currently gets about 20% of its electrical power from coal-fired plants. Pennsylvania is the number two state (behind Texas) in the nation in total production of electricity, supplying 8% of the U.S. need. Pennsylvania only uses 6% and exports the balance to other states.

It is hard to have an objective discussion about coal-fired plants because there is so much emotion and concern about climate change. The hard reality is that the world will have a difficult time reducing the use of coal any time soon. Given that reality, we should focus on something we can do something about it, and that is conversion efficiency. The average current coal-fired plants convert about one third of the latent energy in the coal to electric power. The rest goes off as waste heat.

Northwestern Pennsylvania has large coal deposits but environmental initiatives are decreasing the local demand for coal. Not only do we have lots of natural gas in this area, but technology now exists to efficiently (and with low environmental impact) extract coal gas from our coal. I believe the byproducts are commercially valuable coke (for steel-making) and coal tar (a useful chemical).

Once we have natural gas and coal gas available, we can address the question of conversion efficiency. The newest generation of gas turbines are approaching 60% conversion efficiency which would alone cut CO2 emissions by 33%. A technology that could be important from both from an environmental and a conservation of resources viewpoint is the fuel cell. This device converts a gaseous hydrocarbon fuel gas or plain hydrogen directly into electricity without having to use combustion as in engine generators, gas turbines and coal powered turbine-generators, with their inherent low conversion efficiency and high emissions problems.

Solid oxide fuel cells can theoretically achieve 55% conversion efficiency. The process is exothermal, so coupling the fuel cell with a waste heat recovery system might allow overall conversion efficiency to approach 70% conversion efficiency. This achievement would halve the current CO2 emitted per kilowatt. Further, since the fuel cell portion can operate at temperatures well below that at which oxides of nitrogen are created, those major pollutants of current coal-fired plants would be eliminated.

Local governments and institutions could subsidize research in the above areas with the local institutions of higher learning, augmented by grants from federal and state sources, to develop systems capable of generating electric power from gas without the environmental negative (and poor energy conversion efficiency) of burning the fuel. The area is blessed with a number of colleges and universities that provide a multi-technology base.

The ideal goal would be a series of mine-head (or gas well-head) plants in our coal- and gas-producing counties for conversion of these fuels to electricity more efficiently and with radically reduced emissions, compared to hydrocarbon fuel-burning plants. There might be a partial quick implementation if the currently abandoned coke manufacturing plant in Erie were able to be converted to a coal-gas plant. A facility could be built next to it to house a fuel cell, gas-to-electricity conversion station. (When I was growing up in Brooklyn, all our borough's gas came from a large coal-gas plant of Brooklyn Union Gas).

A very recent improvement in fuel cell technology is the "reverse fuel cell." This permits using electric power applied to the fuel cell to break down water into hydrogen and oxygen. During low system electricity demand periods, the hydrogen can then be stored in bulk storage tanks for use when demand peaks. This kind of bulk energy storage capability is critical for systems dependent on wind and solar power (which vary in output). Currently, the main bulk energy storage systems available are hydroelectric pumped-storage pools.

Can we tap local helium?

The use of helium in industry and medical applications is growing dramatically. The traditional sources of helium, wells in the U.S. (historically the world's major supplier), Qatar, Algeria and Russia have limited capacity. The U.S. has plans to sell off its reserve helium. To make matters worse, helium is one of only two elements (the other being hydrogen) that has such low mass that the earth's gravity cannot hang on to it and it continually drifts off into space.

Helium has been being created over millions of years as a byproduct of the breakdown of radioactive minerals deep inside the planet. The radioactivity generates helium ion, which then picks up electrons to become the inert helium gas. The gas percolates to the surface, typically mixing on the way with natural gas sources.

Why is this gas potentially important to northwest Pennsylvania? Among the places that helium has been found are the Clinton Sands layer which underlie central Ohio at a depth of about 2,500 feet. Unfortunately, these sands are 7,000 feet down when they reach under northwestern Pennsylvania and northeastern Ohio. The good news is that the area has some major, deep fissures and faults that reach down to the Clinton Sand layer. One such fault is northeast of Titusville running from Guys Mills to Centerville. The natural gas in this area has such a high enough helium content that it is already close to being economically feasible to extract the helium.

More from William Miller: Why don't we restore commercial fishing in Erie?

We should monitor this situation. If helium prices continue to escalate as the supply shortfall from the traditional sources worsens in future years, maybe our area could benefit from this opportunity.

Can we create helium?

As will be noted in my future article on energy plans, one of the few remaining negatives to nuclear power generation is the disposal of the spent, but still partially radioactive fuel rods. As noted above, the helium that comes up from deep in the earth is being continually created by decay of such radioactive materials. Since carbon (coal) is a good absorber of radiation, it might be possible to convert some abandoned underground coal mines in the upper Allegheny region to helium-creation plants by providing a means for tapping off the helium from the used rod-enclosing cannisters stored there.

William R. Miller is the former vice president of research and development at AMSCO. He formerly co-chaired the Erie 2000 study for the Erie Conference in 1984 and has been updating and expanding that study in recent years. He has also served as a volunteer docent at the Erie Maritime Museum, published a book on the Battle of Lake Erie and written a pamphlet for the museum on the Erie Extension Canal.

This article originally appeared on Erie Times-News: Engineer lists ways Erie might again exploit its natural resources