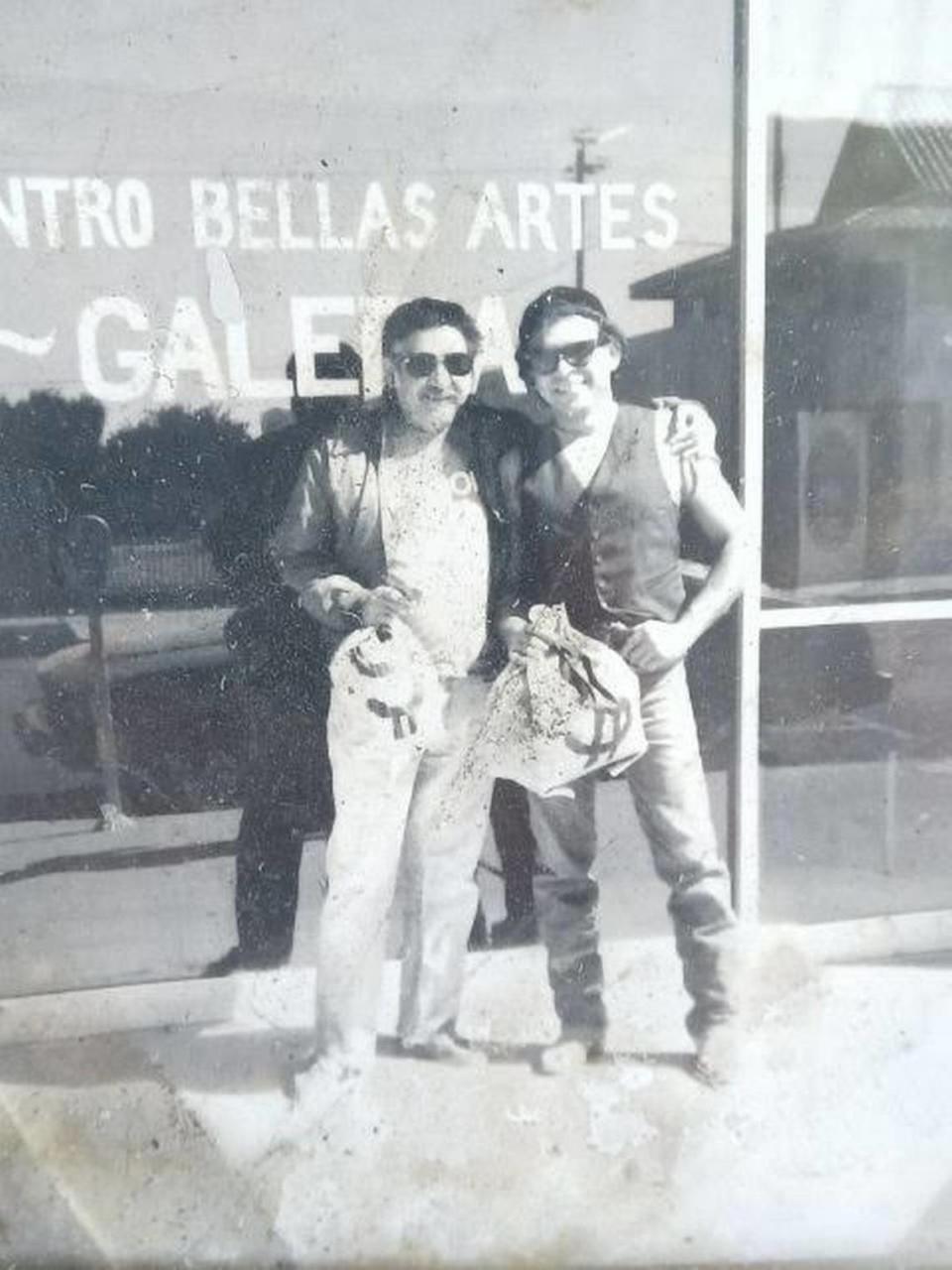

Ernesto Palomino, ‘godfather of Chicano Art,’ muralist, musician, activist, dies at 89

Ernesto Palomino, who grew up in southwest Fresno and became a nationally recognized artist, musician, educator, and activist for Chicano civil rights, died Oct. 26 in Fresno. He was 89.

A former Art professor at California State University, Fresno, Palomino was added in June to the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, and is also recognized by the National Endowment for the Arts. His papers are archived at the University of California at Santa Barbara.

He was a “godfather of Chicano art,” according to friend and artist Pamela Flores. “He was doing it since 1953.” Flores said along with Fernando Hernandez, Palomino was co-founder of La Brocha del Valle, a grassroots community arts organization.

Palomino’s death followed the death of another giant in the Chicano art’s movement, Antonio Bernal, who died Sept 1. Bernal was 86.

Palomino had been in declining health for some time, according to Flores. Services will be Friday, Dec. 15 at St. John’s Cathedral in Downtown Fresno.

Palomino, who played drums and piano, also performed over the years with musicians that included Lionel Hampton, Woody Miller, Muddy Waters, and BB King, said Flores.

Palomino and Ezekiel Lee Orona are recognized as the first muralists to paint Chicano-theme murals in Fresno and Madera in the early 1970s.

Born to farm worker parents, Palomino attended Edison High School, but never graduated until earlier this year, when he was handed his diploma In a special presentation by Fresno Unified School District officials.

Instead, he dropped out in 10th grade because he felt he was being mistreated by his math teacher, and joined the Marine Corps, said Flores.

While at Edison, however, his talents were encouraged by art teacher Elizabeth Daniels Baldwin, who in 1956 helped him publish his book of early works, “Black and White: Evolution of an Artist.”

Palomino put his artistic journey in gear with the autobiographical film, “My Trip in a ’52 Ford,” for a Master of Arts project at San Francisco State College. The film included sculptures he created during his self-described “Gabacho (gringo) Art” period.

Palomino also spent time in Denver and worked for the Migrant Council and joined La Raza Unida party.

In 2004 when he was honored by KVPT, Valley Public Television, he said of his work: “It’s something that keeps me young, in love. It’s like being in love. As long as I have that, I have nourishment. I don’t get depressed. I get excited.”

Longtime friends describe Palomino as a man dedicated to his community and his art.

His artistic ventures entered a new phase when he and Orona created the “Farmworkers” mural on the wall of La Flor de Mexico restaurant, at Tulare and F Street in Fresno’s Chinatown, in 1970.

In 1972, the two painted “Raza” on a theater wall in downtown Madera, stirring controversy with city leaders in the conservative farm town, something Palomino was not afraid to confront..

Orona, reached at his home in Las Vegas, said trouble started when the two realized they needed a scaffold to paint the mural. City planners wouldn’t grant permission for its use, so Palomino got help from California Rural Legal Assistance to overcome the opposition.

“They were just old guys set in the ways,” said Orona, who was then an Army veteran of the 101st Airborne, and recently back from Vietnam.

“They didn’t want anything to do with culture and freedom. We changed their minds.

“It was a good battle.”

Another longtime Palomino friend, Al Reyes, then a Fresno television reporter, noted Palomino was quick to add humor to his artistic endeavors, once cutting apart a farm labor bus and converting it into an Aztec eagle float for a Chinatown parade.

On another occasion, he acquired an old military uniform, replete with medals, and called himself “Major Disaster,” and “General Disorder,” for an event with the California Arts Council.

Reyes said Palomino’s residence at San Francisco State likely helped add a beatnik dimension to his personality.

“He was a lot of fun to be around,” said Reyes.

But that did not make him the most popular member of the faculty at the then somewhat uptight Fresno State Art Department.

Once called on the carpet by department for his outside activities, Palomino countered that his community involvement was a good thing. Reyes helped out, providing video tapes of Palomino’s participation in popular events to prove it.

“They backed off me,” Palomino then noted, triumphantly.

New York City musician Max Olivas called Palomino “a phenomenon.”

Olivas, a native of the Cutler-Orosi area of Tulare County, credited Palomino with inspiring him to learn about the arts after the two met while Olivas was still in high school. The agricultural community was a cultural desert at the time, he added.

“Jazz and art, Ernie brought those things there,” said Olivas.

Palomino was called “Gunner,” by friends, short for “tailgunner,” an ironic joke on his thick eyeglasses. It was only later, when Palomino went to an eye doctor that he learned his vision was clouded by cataracts, Olivas said.

He remembers occasions when Palomino would load up Olivas and other friends in a yellow Packard convertible and drive to the foothills, where the group would spend hours sketching landscapes.

Olivas and Palomino would later reconnect in San Francisco, where Olivas played trumpet as part of the modern jazz movement, and Palomino playied piano.

Now living in Manhattan, Olivas said his life’s journey after meeting Palomino took him deep into Mexico for encounters with Mexican curanderos, and then to New York City, where he arrived in the 1970s with less than $10 in his pocket. That may have never happened had he not met Palomino in his younger days.

“We both kind of “gravitated to places that were more exciting and more fulfilling, Olivas said. “Certainly, I think that we had an impact on one another.”

Palomino was an inspiration for artist Sal Garcia, as well.

“He was considered a genius… He was fairly well known by the time he got his Master’s (degree),” said Garcia from his home in Vallejo.

“He plugged me into the art scene (in San Francisco), and it became my career.”

Garcia credits Palomino with teaching him the concept of “putting your art at the service of the community,” by creating posters, logos and other artwork to promote activist causes.

“Fresno lost a giant in the arts community,” said Garcia.

“He was very similar to (Fresno Armenian-American artist) Varaz Samuelian.”

“They (both) should have gotten more credit for what they did.”

Palomino is survived by his daughter, Jocelyn Palomino and sons Fresno Palomino and Joaquin Palomino, all of Denver; Billy Hunahpu Palomino Anaya of Bakersfield; Calvin Xbalanque Palomino Anaya of Fresno; and Granddaughter Sol Segura and Grandson Esteban Segura, both of Denver.