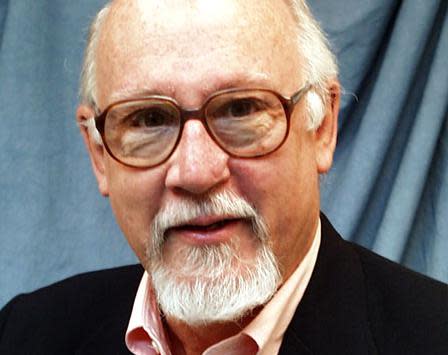

Essays provide startling news about British birds, British society | DON NOBLE

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Helen Macdonald, working as an historian of science at Cambridge University, was plunged into grief by the death of her father.

To perhaps heal herself, to focus on something besides her loss, she took up the task of training a goshawk, a large and dangerous raptor.

The story of that experience produced in 2014 the powerful, lyrical “H is for Hawk,” a bestseller which won at least seven literary prizes and was declared one of the 10 most important books of the year.

Macdonald also became an essayist/contributor to the New York Times magazine and the “New Statesman,” where many of the 41 essays in this new book appeared.

More:Lively book tells fascinating tales of Civil War spycraft | DON NOBLE

“Vesper Flights” does not have a biographical through line, like “Hawk,” but is held together thematically and by subject matter. As one might expect, the pieces are mostly about the slowly disappearing wilderness, the threats to the environment and, especially, the lives and habits of different birds: their nests, their nearly unbelievable migration journeys, and the correlations between the world of birds and our own.

Sometimes, as we destroy natural habitat, the birds come to live with us, in cities, in skyscrapers.

How do the birds, even the little hummingbirds, travel thousands of miles, sometimes in flocks of hundreds, even thousands, at enormous altitudes, guided by the stars and earth’s magnetic lines?

Swifts, we are told, don’t come down at all, but fly for two or three years at a time, sleeping, eating, drinking, mating, bathing, in the sky.

People, she reminds us, also migrate, especially if their homes have been reduced to rubble and they seek the simplest things: “freedom from fear, food, a place to safely sleep.”

In “Hawk” and in these essays, Macdonald runs into Brexiteers, usually older Brits, who long for the past as they understand it, and its traditional symbols: the stag, the swan. It’s not so simple, she says.

The beloved and endangered hawfinches, for example, who live often in old woodlands near stately homes, and therefore are sometimes called National Trust finches, are presumed part of England’s ancient past.

People may believe that hawfinches flew around King Arthur, but no. The first two, "a vagrant pair from the continent," arrived about 1850. They have assimilated well, it seems.

My favorite essay of all is “A Cuckoo in the House” in which we learn that British author and radio personality Maxwell Knight was an expert birder, a specialist in cuckoos.

Cuckoos lay their eggs in other birds’ nests, the hosts unaware. When the chick hatches, he kills his nestmates, eggs or chicks.

Maxwell Knight, it turns out, was “M,” head of MI5, well known from James Bond movies. He taught agents to observe vary carefully, the smallest details, just as a naturalist must do.

He secretly placed agents in various subversive organizations. As an ornithologist, he wrote of the proper relationship of handler to wild thing, remembering that the wild thing, bird or spy, is never really tame, could turn at any moment.

And "M" himself, we are told, was a deeply closeted homosexual “picking up rough trade in local cinemas”: not what he seemed either.

One of the most provocative essays is "Birds, tabled." Here Macdonald takes up the question of keeping birds as pets. There is considerable moral outrage against keeping birds in cages. It is in fact, unlawful to cage a wild bird. In fact, it is culturally correct now to see keeping caged birds as immoral, unethical. But many birds are raised in captivity and their owners love them dearly for their companionship and their song. The birds are well cared for, and interacted with constantly and seem to be happy. But keeping birds in cages is the hobby of "working-class and minority communities, like miners, immigrants, East-End Londoners, Romani and Irish Travelers."

On the other hand, flocks of swans and ducks are kept on private ponds and lakes, by the well-to-do. These birds look wild but they cannot fly away because "the end of one wing [has been] cut away to stop them escaping." One cannot help but think of Henry David Thoreau in "Walden” alone in his cabin. Thoreau says, “I found myself suddenly neighbor to the birds, not by having imprisoned one, but having caged myself near them."

A surprising essay, not to do with birds, concerns hares. The work of the pioneering ethologists, like Conrad Lorenz or Robert Ardrey, taught us the sometimes startling parallels between human and animal behavior. All species, they said, establish hierarchies and compete for mates.

So, in the essay “Hares,” when she sees hares, on their hind legs, boxing, she first assumes that these are males, fighting for dominance: to the winner goes the doe.

But no — these are “does unwilling to mate with bucks making sexual advances on them.” Macdonald identifies this as “an animal analog to a form of violence just as much a feature of our society, though only in recent years have we begun to openly speak of it.”

Don Noble’s newest book is Alabama Noir, a collection of original stories by Winston Groom, Ace Atkins, Carolyn Haines, Brad Watson, and eleven other Alabama authors.

“Vesper Flights: New and Collected Essays”

Author: Helen Macdonald

Publisher: Grove Press

New York, 2020

Pages: 304

Price: $27 (Hardcover)

This article originally appeared on The Tuscaloosa News: Essays provide startling news about British birds, society | DON NOBLE