EU bucket list: 12 magnificent pieces of architecture

Is there such a thing as European architecture?

It’s a thorny question at the best of times - and obviously, our current political era fails that inclusion. But as Nickolaus Pevsner’s Outline of European Architecture (1943) noted, there are great architectural threads through time, and his “changing spirits of the changing ages”, drew the evolution of European building from Romanesque basilicas through Gothic cathedrals, Renaissance villas and Baroque churches, much drawn from the well of Roman and Greek classicism. To which we could add a host of styles and types that crossed borders: classicism, gothic, Art Nouveau, modernism, high-tech through to the ‘icon’ urinating contests of the last two decades.

There were always tower-height contests and different forces, from Moorish Andalucia to the Renaissance, through grandiloquent kitsch like Albert Speer, architect of the Third Reich, to Victor Horta, the great Belgian Art Nouveau architect.

Europe’s city planner architects gave powerful expressions of place from Karl Friedrich Schinkel in Berlin, Georges-Eugène Haussmann in Paris and Jože Plečnik in Ljubljana.

As Spain-based architect Fabrizio Barozzi once said: “I see European architecture as more of a collage of entities, than of one single identity.” Like Europe’s heterogeneous social composition, that’s just how it goes – the continent remains a huge laboratory.

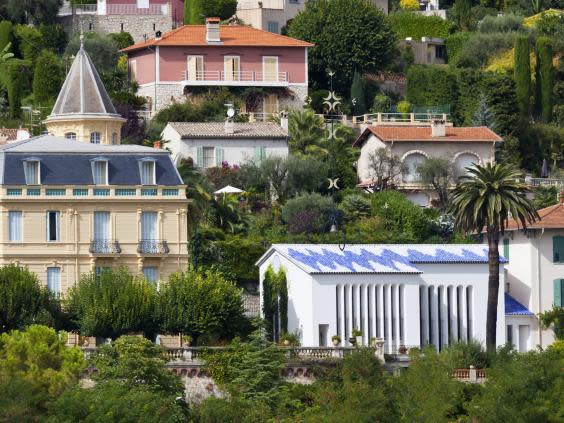

Chapel of the Rosary, 1948-1951, Henri Matisse, Vence, France

In a back street of a pleasant town, this chapel is the masterpiece of artist Henri Matisse. At the ripe old age of 77, Matisse created it for a chapter of Dominican nuns, including his nurse and muse Monique Bourgeois, with art worshippers still playing second fiddle to the order. And if the whitewashed exterior is lovely, then the interior is divine: yellow, green and blue stained glass contrasting with black-and-white ceramic murals. It took an atheist to make one of the loveliest buildings in the world.

Fernsehturm (Television Tower), 1965-69, Fritz Dieter, Günter Franke and Werner Ahrendt Central Berlin, Germany

The Soviets just loved their television towers, and this is perhaps the finest. Built by the German Democratic Republic (GDR) during the Cold War, at 368m it’s the tallest structure in Germany, gazing far over Berlin and taller than anything in the Western part of the city. Now subsumed by the trend for ‘ostalgie’, the recherche affection for Communism past, you can dine in its revolving restaurant Telecafe. But in winter you can still sense the all-seeing eye of the GDR.

Finlandia Hall 1967-71, Alvar Aalto, Helsinki, Finland

A discreet grandeur pervades the Finlandia Hall – a congress and event venue in central Helsinki. Aalto designed everything from doors to tiles, and it has a lovely position by Töölönlahti Bay in this archipelago city. With long horizontals and just-so details – not to mention a restaurant and concert hall – the Finlandia Hall is a kind of meditation in itself.

Druzhba Holiday Centre 1984 Igor Vasilevsky Yalta, Ukraine

The James Bond baddie school of architecture. This cylindrical Holiday Centre on Ukraine’s Black Sea has that Cold War space-race aesthetic down pat – indeed, legend has it that in those febrile years, the US thought it was a new and sinister military building. Perched on a hill, and supported by legs and trusses, guests enter via a glass tube. All the rooms are oriented to get a good view, hence that prickly hedgehog look. A late Soviet gem.

Alhambra 889 Granada, Spain

The Alhambra started as a fort in the Moorish occupation of Spain. When the Reconquista happened, it changed – apart, that is, from the courtyard, fountains and gardens. It’s a world-class wonder for a relatively small town and almost didn’t survive the 18th and 19th centuries. Now UNESCO-listed and with the Museo de Bellas Artes and the Museo de la Alhambra within, the whole site is a delight. Or as author Washington Irving put it: “How unworthy is my scribbling of the place?”

Colosseum, 70–80 AD, Vespasian, Titus Rome, Italy

It’s hard to think of the huge Roman ovoid without thinking of a swords and sandals epic starring say, Charlton Heston – and equally hard to enter it without the clang of sword in the mind’s ear. Yes, the Colosseum really delivers and the Flavian Amphitheatre (as it’s also known) holds up to 80,000 spectators, only marginally less than Wembley Arena. As you clamber over the stalls, remember that they watched executions, classical dramas, animal hunts and battle re-enactments right through to the medieval era. Just watch out for the scammers in plastic centurion helmets outside.

Field of Miracles 11th century onwards Bonnanno Pisano and others Pisa, Italy

It’s thronged, and absurdly touristy, with annoying people taking photographs – and you’re one of them. But the Campo di Miraculo (a term coined by poet Gabriele D'Annunzio) really is worth it. There’s the Cathedral or 'Duomo', the Baptistry, the Monumental Cemetery, and of course, the Leaning Tower. The mixture of green grass and the white marble is exquisite, and Pisa itself straddles the River Arno like a dreamscape (indeed, it’s those riverine marshes that make the ground unstable and caused that fateful lean). Come on a winter morning, avoid the tat and you’ll see a dreamscape – yes, it is miraculous.

Skara Brae, 3200BC-2200BC, Hebrides, Scotland

At many archaeological sites, exciting and enigmatic as they are, you don’t get an empathy hit of how those old-timers lived. But at Skara Brae, you do. Here, in Europe’s best-kept Neolithic settlement – eight houses in all – you’ll find 5,000-year-old furniture, gaming dice, tools and jewellery. It was only the serendipity of a storm in 1850 that we even have Skara Brae, once a hillock. Thought to be Iron Age, radiocarbon dating pushed it back to the late Neolithic. But when you see the square room, with a central fireplace, a bed, and a dresser on the wall opposite the doorway – you’ll think, plus ça change.

Lincoln Cathedral, 1073, Bishop Remigus/Hugh of Avalon, Lincoln, England

It’s not even the biggest of the English Cathedrals, and is eclipsed by Salisbury, beloved by Russian poisoners. But many (including John Ruskin who described it as "out and out the most precious piece of architecture in the British Isles”) think it's the best. Perhaps it’s the three towers that look over the flatlands or its height – in 1311 it once pipped the Great Pyramid of Giza to be the tallest building in the world – or the setting at the top of quaint Steep Hill, or the rich collection of Anglo-Medieval art including one of the four copies of Magna Carta.

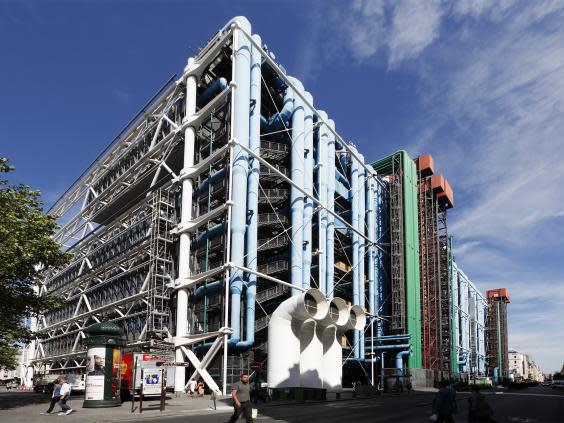

Pompidou Centre, 1977, Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers Les Halles, Paris, France

When the Centre Pompidou opened in 1977, it was startling – particularly its escalators, which ran outside the building. The Italo-British duo of Piano and Rogers won a competition with their colourful 'inside-out' boiler house: so celebrated was it that Rogers was parodied in UK satire series Spitting Image with his intestines outside his body. The Pompidou (aka the ‘Beauborg’) exceeded expectations, and with a ‘multi-disciplinary’ ethos and a space outside full of inter-railing students, it changed the face of the modern art museum and ushered in the era of the artistic ‘icon’.

Sagrada Família, 1882-2026?, Antoni Gaudí, Barcelona, Spain

This eccentric architect is Barcelona’s great mascot and Templo Expiatorio de la Sagrada Familia, his masterpiece. Towering over Barcelona, it’s the exemplar of Gaudi’s sinewy Gothic-meets-Art Nouveau style: utterly impressive and vertiginous. Amazingly, it’s due to be finished in 2026, 100 years after Gaudi’s death, when it will have six full spires, topping out at 172m and making it the tallest church building in the world. Consecrated by Pope Benedict XVI in 2010, it’s a great double visit to another Gaudi highlight Parc Guell, with its long mosaic bench.

Rietveld Schröder House, 1924, Gerrit Rietveld, Utrecht, Netherlands

The best thing about this primary-coloured, cubic house is that it’s so unexpected, tucked away in a side-street in Utrecht. Built by Reitveld for a female client, his big idea was to design it without walls so that one could change it whenever one wanted. By all accounts there was a lot of blood, sweat and tears – and a client-architect affair – but now it’s revered as the domestic expression of the avant-garde art movement De Stijl. If you’re near Utrecht, go – it has a real cranky charm.

Architects’ choose their favourite European buildings

Paul Monaghan, Allford Hall Monaghan Morris (AHMM): “My favourite European building has to be the Pompidou Centre. It was so radical when it was built 40 years ago and still is today. I first saw it when I was 19 and it made me realise that public buildings could be optimistic and forward looking. The long rear elevation with coloured ductwork is a real triumph while the civic elevation with its cascading elevators, always full of people, shows that visionary architecture can be both populist and challenging.”

Alison Brooks, Alison Brooks Architects: “The Staatsbibliothek (State Library) in Berlin by Hans Scharoun is one of my all-time favourites. It’s an organic, meandering and hugely generous building. It feels like a landscape populated by panoramic mezzanines, powerful columns and integrated, sculptural lighting. It’s civic architecture that makes you feel lucky to be a citizen.”

Chris Wilkinson, WilkinsonEyre Architects: “My favourite European building is the Barcelona Pavilion by Mies van der Rohe constructed in 1929 for the International Exposition in Spain. It was one of the first buildings to integrate the inside and outside spaces using vertical and horizontal planes. It is beautifully crafted with travertine stone walls and the roof is supported with cruciform steel columns finished in chromium.”

Paul Williams, director at Stanton Williams: “Many buildings move me, but none quite like Carlo Scarpa’s Castelvecchio Museum in Verona, Italy. Scarpa’s reworking of a 14th-century castle (in 1959-73) balances new and old, sensitively revealing the history of the original building, at the same time celebrating new contemporary interventions. One of the finest and earliest examples of an architect successfully juxtaposing old and new, and creating something greater than the sum of its parts. This project remained an ever-present inspiration today.”

Rab Bennetts, director at Bennetts Associates: Palladio’s powerfully elegant Basilica in Vicenza, still the focal point of the city nearly 500 years after it was built, is as European as the cafes and communal meeting spaces it accommodates."

Eric Parry Parry, founder, Eric Parry Architects: “The Royal Festival Hall on London’s South Bank (1951) owes its openness and formal character both to Nordic precedents and the pre-Second World War migration of architects like Walter Gropius, whose three years in London helped to graft European modernism into the British mainstream.”

Oliver Bennett is the author of Amazing Architecture: A Spotter's Guide (Lonely Planet £7.99)