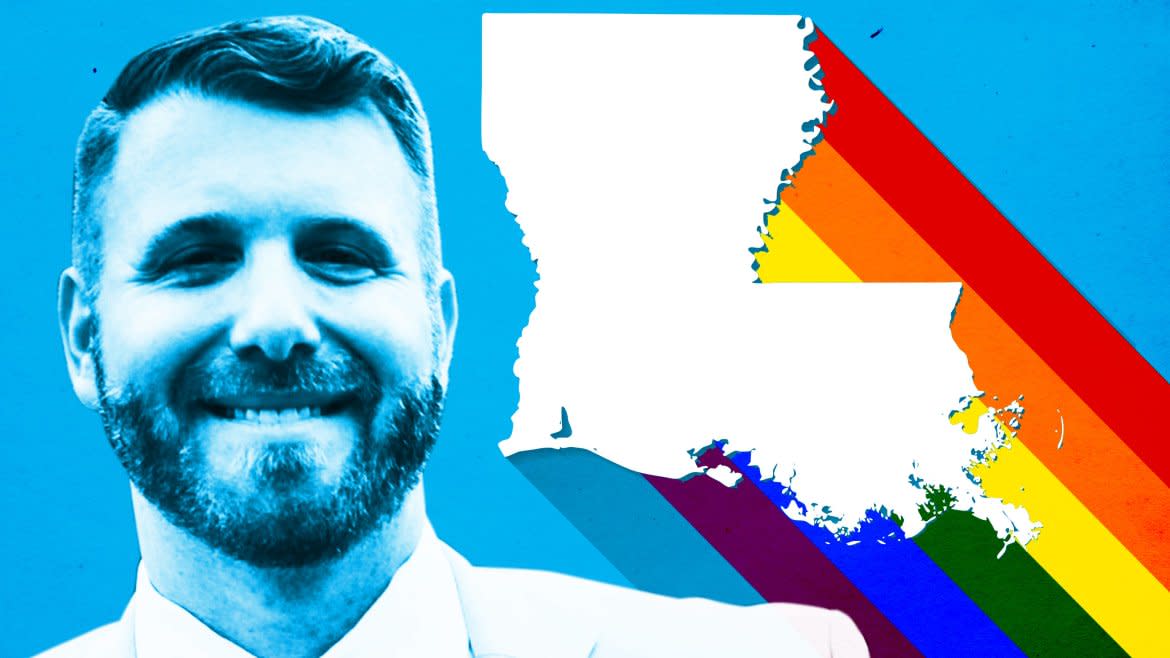

Evan Bergeron Is Gay, Catholic, and Determined To Be Louisiana’s First Out LGBT Legislator

Evan Bergeron’s mother Paula is not just thrilled about her son’s candidacy in New Orleans’ upcoming District 98 primary election, she is raring to leaflet and canvass.

“She called me and said, ‘Let me know when we can come and knock on doors for you,’” Bergeron told The Daily Beast. “This really is a family endeavor. My mom also just bought my dad a new pair of walking shoes, so they’re both ready to go.”

Bergeron, a lawyer, could make history in the primary, set for Oct. 12: if victorious, he would become the first openly LGBTQ person ever elected to the Louisiana state legislature and only the second out LGBTQ elected official in the entire state (after Aaron Moak, in the East Baton Rouge Parish City of Central). Louisiana is one of just five states to have never elected an out LGBTQ state legislator.

Danica Roem, Trans History Maker, Fights Another Anti-LGBT Candidate—and Their Donors—in Virginia

On Tuesday, Bergeron received the endorsement of the influential LGBTQ Victory Fund, which supports out LGBTQ candidates across America.

Annise Parker, CEO and President of the Victory Fund, told The Daily Beast, “Louisiana is not a low-equality state. We might even call it a negative-equality state: no out LGBTQ representatives in the legislature, no statewide LGBTQ protections, very few local LGBTQ protections. So, it’s important that there are people in public positions who articulate our issues and advocate for us.”

Bergeron is standing against six other Democrats in an area of New Orleans known as Uptown. There are no Republican or Independent candidates standing in the district. In this “jungle primary” if one candidate wins a majority of the turnout, they win the seat outright; if not, the two leading candidates will compete in the general election on Nov. 16.

“I am confident because our message to voters is, ‘We need someone in Baton Rouge who will be effective from day one,’” said Bergeron in his first major interview. “I’m not someone who needs on-the-job training. On day one I’ll roll up my sleeves and get on with it.”

Parker said the primary featured “a group of many strong Democratic candidates. It’s not an easy race for any of them. Mr. Bergeron is a strong candidate, but the winner will identify their supporters and hold them through the primary. Being LGBTQ will not be the make-or-break issue. This is about making sure voters perceive him as someone who understands their daily lives, understands the issues in the race, and has plans to address those issues.”

Like Danica Roem, who made history in Virginia in 2017 when she became America’s first out trans legislator and who is passionately devoted to issues of congestion and roads, Bergeron is also focused on local issues, like flooding in New Orleans, education and teachers’ pay. Teachers in Louisiana, he said, are paid well below the southern average.

Bergeron said he was immensely inspired by Roem after she was elected to represent the 13th District in the Virginia House of Delegates in 2017.

“She had a message of hope, and she also emphasized, ‘Let’s talk about what affects you,’ and focused on fixing Route 28. I’m not going out and saying to people, ‘I’m Evan, the gay candidate,’ but ‘Let’s talk about the fact the city keeps flooding every time we get two inches of rain.’ It’s the product of a drainage system that is over 100 years old, and climate change.”

The prospect of making history in Louisiana “means a lot” to Bergeron. The 33-year-old (he will turn 34 just before the primary) was born and bred in the state. His coming out journey, which he talked candidly about for the first time to The Daily Beast, was long and difficult. He is religious, a Catholic. Like the Episcopalian Pete Buttigieg, Bergeron’s faith means a great deal to him, but it has been a painfully tough personal journey to reconcile his religious beliefs and sexuality.

Bergeron also worked in the Louisiana State Senate for seven years—regular sessions 2003 through 2009—as the session aide to Senator D.A. “Butch” Gautreaux, a Democrat from Morgan City, Louisiana.

During that time, Bergeron “saw what the titans of the state senate were accomplishing, but when I was struggling with my own identity and who I was, I always thought if I ever wanted to be my true self I would never be able to be one of them.”

Now, four years after marriage, equality was achieved, “it’s a different world,” said Bergeron. “I’m happy to be able to be potentially the first LGBT member of the legislature, and to be able to show an LGBT kid like me in rural Louisiana, who thinks there’s something wrong with them, who is not able to be their true self or do what they want to do, that they can do whatever they want to do and be happy.”

The Victory Fund’s Parker said it was becoming easier for LGBTQ candidates to run, as more and more people generally came out, “comfortable in our skins,” to family, friends and their communities.

Indeed, coming out can be politically beneficial. Parker has found that “there is some kind of calculus in people’s heads that ‘If you’re being open with me about your sexual orientation or gender identity, you’re probably going to be honest with me about other things.’ Americans are hungry for honesty and integrity. We’ve found that people feel, ‘I don’t have to agree with you about everything, but I trust you to know and stand up for the right things.’”

Bergeron said the dearth of out LGBTQ officials may have something to do with Louisiana being “deeply religious where people talk about faith and family. When I grew up, I turned to faith to mask who I was and do the things I thought it was necessary to do.”

It’s a “luxury” to live in an out life in New Orleans, Bergeron said, and achieve what he wants to achieve. “But I recognize firsthand the societal pressures that plague much of rural Louisiana.”

Bergeron grew up in the small swamp town of Pierre Part. His mother is a retired public schoolteacher who now works at a flower shop “to stop herself from getting bored.” His father Ricky has worked for many years in construction, particularly within the state’s chemical refinery industry. Bergeron’s younger brother Stefan works in construction too; his younger sister Chelsie is a 7th grade teacher.

Growing up, Bergeron laughed, he knew if he ever misbehaved at school it would get back to his mom quickly. “I had that first child syndrome of having to excel at everything. I was very self-sufficient. I tried to be like the boys around me. I was in Cub Scouts, Boy Scouts and played baseball and football in middle school.

“I was trying to fill that role I saw all the men in the community and my friends filling, while still having this internal struggle. I thought it was important people see me as a regular normal kid like everyone else. I was active in the Catholic Church, I still am a Catholic.” He did voluntary work in the community (the notion of which means a lot to him).

“There was a lot of tension,” he said of the conflict between his religion and sexuality. He recalled getting confirmed at around 14, and “what we were taught, the impression I got, was that everything I was feeling and going through was wrong. It was a test of my faith, I was told. The message I was getting was: ‘You’re not working hard enough to pray being gay away, you have to work harder.’”

It was a “strong and persuasive narrative,” Bergeron found. But, he added quickly, “I don’t want you to think my opinion is that religion is bad. Religion has an important place in many people’s lives. It has an important place in my life. I feel the importance of spirituality, of believing a spirituality. There is something out there in order to do good for others. I believe I have to be a good person. I believe there are consequences if I’m not a good person. That’s what religion means to me. That’s why I still do call myself a Catholic.”

Bergeron’s journey to self-acceptance and coming out was a complex, troubled one. He said it took him 10 years, beginning around age 10. “I didn’t actually officially admit to anybody out loud that I was gay until I was 20.” On his website, he writes that his story is “neither easy nor orthodox.”

Did he ever feel depressed or worse, suicidal?

“I had a little bit of trouble in college. I would go into funks every now and then and eat a lot of food. It was a slow process, processing my emotions. We didn’t really put a big emphasis on mental health at the time. Now, I think we need to push it harder as part of our state health-care policy, partly because of my own experience. Had I been able to receive a kind of appropriate mental health treatment it probably would have done wonders for my development.”

As a teenager, Bergeron had same-sex sexual encounters with friends, but kept it quiet. At university he met gay people, “but I always saw that they were subject to a certain amount of ridicule when they were not there. Louisiana has passed numerous bullying statutes, but not one iteration has included sexual orientation and gender identity, which is needed.”

At 20, Bergeron started hanging out with “theater and music kids,” and found people for the first time who understood and supported him as a gay person, which led to him “putting up a barrier” between himself and the people he had known in his past and hometown. “Even today that barrier was built so high in my brain it takes a second to knock it down.”

Friends of his from the South have gone through similar. One friend had been dating a guy for two years, and kept two separate phones: one for his boyfriend and the other for his parents. He was terrified they would find out he was gay and ostracize him. “I know that story plays out over and over again in Louisiana and the South. In New Orleans we have problems with homeless LGBT teens and trans women being murdered.”

Bergeron himself was “incredibly nervous” about coming out to his family. “I waited until it was almost too obvious, and said, ‘Oh hey, I’m gay. You knew that right?’ I do regret doing it that way a little bit. Another friend had the conversation with his parents when he was in college. It took a toll on his parents, having to interact with the community when people were so closed-minded. I regret not pushing the envelope as much as he did. I have such great respect for the courage he had, and I didn’t, in college.”

How did Bergeron’s parents respond? “It was fine. My dad started crying. I think they were relieved. I was relieved as well obviously.”

Bergeron wishes he could tell his younger self that he was as worthy of happiness as anyone else; and that he didn’t need to be as unhappy as he was for so long. “It took me a really, really long time to get where I am now. But I am happy with who I am and what I have done. A couple of years ago I’m not sure I would have been able to say that.”

Having “mental health check-ups was key,” as was stopping resenting his parents. “When I realized I was surrounded by love from people I love and love me, that was when I found that peace. I didn’t come out to my parents until much later. The reason I did not come out to them was because I was afraid. I heard horror stories of people who had come out and were thrown out on the streets. My silence was more self-preservation than anything else. I fought with it a lot internally.”

After Bergeron came out to his parents, all parties had a “tacit agreement” not to retrospectively litigate “what could and should have been done better. I wouldn’t want to go back and re-analyze every look and statement. I don’t think that would be constructive. We are just happy to be in a position where I’m honest, we’re honest, and we can move forward with how things are.”

Bergeron has learned to live with the Catholic Church’s homophobia while cherishing his own faith.

“I’m a strong believer. You just gotta find the right church. There are so many Catholic churches in New Orleans preaching so many versions and doctrines of Catholicism.”

Bergeron recalled going to one church after the 2015 Supreme Court marriage equality ruling, “which I was so happy and thankful for,” and “making the mistake of going to a church that is anti-homosexuality and teaches homophobia. The priest was going hard on how homosexuality was an abomination and our country was being sucked in by Satan. I never told this to anyone, especially my parents—but that was the first time I walked out during a sermon. I haven’t set foot in that church ever since.”

His present church, St. Francis of Assisi, is very LGBTQ-friendly. “Your church should be a place you feel welcome, together with others in a spirit of hope. I can go to St. Francis and come out with a smile on my face, and know the message from the pulpit is that gay people are as worthy of love, happiness and God’s grace as anyone else. It’s refreshing.”

However, Bergeron concedes it is an ongoing “personal struggle” to deal with the Catholic Church’s institutional homophobia.

“I do feel some people in the United States are using religion as a weapon, which is not what it’s supposed to be. I think my role in this is to be an ambassador. Like Mayor Pete, I have faith. The difference is I am Catholic, and I obviously do not agree with some of the major Catholic dictates about homosexuality. I hope the larger Catholic Church moves in the direction of my local church. I’m not necessarily hopeful it will, but if I can do my part to help it, I will.”

Had he ever thought about leaving the Church and giving up his faith, given its larger negative messaging about homosexuality?

“Definitely, I did. There were times when I wondered if there was a place for me. But I have always kind of maintained that your faith is something that is special to you and what you make it.”

Bergeron said he had a “big problem” with laws being formulated around so-called “religious liberty.” He is a “big believer in the First Amendment as it relates to the establishment and free exercise clauses. For me, they mean that I can’t do something because of my religion, not that you can’t do something because of my religion.”

A religious liberty-style law was proposed, and ultimately rejected, in 2015 in Louisiana. “One of the reasons I have put myself forward for election is to make sure there is someone in the legislature who can tell people why these laws are bad for business and the advancement of society,” said Bergeron.

That Louisiana does not have employment protections for LGBT people also angers Bergeron. “One of the biggest job killers in Louisiana is our insistence that LGBTQ people are not entitled to the same rights as everyone else. Employers and companies have passed us over because we don’t have employment protections for people who are LGBT. This is not a way to run a society or economy. People should be secure in where they work.”

Bergeron claimed some of his election opponents had in 2018 supported the Louisiana Attorney General’s ultimately successful bid to have the state Supreme Court block Governor John Bel Edwards’ attempt to enshrine employment protections for LGBT people employed by the state government.

“They call themselves progressives. I call bullshit. You can’t call yourself a progressive if you support an attorney general who actively works against protections for the LGBT community, and Medicaid expansion to help poor communities get healthcare.”

Bergeron said he would “absolutely and happily” file another LGBTQ employment protections bill if elected, and build on the “years of work” already done by LGBTQ organizations in Louisiana.

The Trump administration’s animus towards LGBTQ people and rights has been a “weird blessing” in that Bergeron has been able to talk to rural voters and people he grew up with about LGBTQ issues. “Now they can put a face to the anti-LGBT policies coming out of this administration. Now they can see in a concrete way how this administration is actively hurting people they know.

“It brings things in to focus as never before for them. Before I came out they saw these issues as affecting ‘other’ people they were never going to meet or care about. But now they see it as something affecting someone in their lives, and that it’s bad and wrong.”

One of the biggest blocks to LGBTQ candidates standing, especially in places where there are few or no other out LGBTQ officials, is the psychological hurdle of “I don’t see anybody else, can I do this?” said Parker. “Once you get past that, you have to learn how to become master of your own narrative,” Parker said.

“For voters who attach importance to your orientation or identity you have to turn it into a positive or neutral. Some of our candidates will even use it. ‘Coming out taught me this.’ ‘I can identify with your struggle because this was mine.’ Every candidate has to figure out how to talk to voters understand what their lives are like.”

Bergeron was in New York when the Victory Fund endorsed Pete Buttigieg in the Democratic presidential race on the eve of World Pride, and was particularly inspired by Parker saying, “Just the fact of running changes the debate.” To receive the organization’s endorsement makes him feel “over the moon. To know the Victory Fund is endorsing me, some guy in New Orleans trying to do good things in the state legislature, is almost surreal.”

This endorsement comes in the wake of the Log Cabin Republicans’ endorsement of Donald Trump for his 2020 re-election campaign. “I find it difficult to see in today’s climate the Republicans standing for anything that benefits the LGBT community. The Republican Party needs to recognize if they really do want to be a big tent party and welcome everyone, one of their platforms can’t be the dis-recognition of someone else’s humanity.”

The Reality-Defying Shame of Log Cabin Republicans Who Endorse Trump

Bergeron said he felt “lucky” being an out-gay candidate in the South. New Orleans was as welcoming as the image of the city suggests, he said.

Nothing negative has been said—so far—about his sexual orientation. Bergeron thanks Seth Bloom, an out gay member of the school board (who ran for City Council in 2017), and attorney Richard Perque, who last year competed for an open seat on the Orleans Parish Civil District Court, for “blazing trails. As people say, ‘I stand on the shoulders of giants.’ I appreciate what they have done for our community, and paved the way for me to do this.”

Bergeron expects anti-LGBTQ groups to mobilize if he is elected to office. “I am prepared for them to come after me. I am prepared for that. It’s taken a lot of introspection and hardening of my constitution, but we’re going to chase hate head on and meet it with love.”

He decided to enter politics because “Louisiana is my home. It’s the only home I ever had and as far as I’m concerned the only home I’m gonna have. It got to the stage where I couldn’t bear to see the lawmakers in Baton Rouge run it into the ground.” He was particularly angered by a reform of tax bands that hurt the poor, not wealthy, and the passing of a bill that would have outlawed abortions after six weeks, even in cases of rape and incest.

“After that I said to myself, ‘We have completely lost our moral bearings.’ I was the angry guy on Twitter, then realized I had the experience of how that building works.”

When Bergeron started working at the state legislature fresh out of high school in 2003, he “mostly fetched the Senator’s coffee and carried his laptop case around,” he recalled. “As I continued to work for him, I became a trusted adviser and policy analyst for him and would manage his Baton Rouge office during legislative sessions.

“My typical duties in the latter sessions of my tenure would be to manage his calendar, prepare him for hearings, brief him on bills of note before Senate floor action, assist other staff in preparing amendments, and generally facilitate his legislative agenda. It may have been my favorite job of all time.”

But the law called out to him first, thanks to being coached in mock trials at high school by Judge Jane Triche Milazzo, now a US District Court judge for the eastern district of Louisiana, who “commanded any room she was in.” Bergeron studied political science at Louisiana State University, then, from 2008, attended law school at Loyola University in New Orleans where he has lived ever since.

Bergeron and I spoke the day he left the law firm Deutsch Kerrigan. It was “an amicable divorce,” he said. He said the firm didn’t like its associates to be as overtly political as Bergeron’s candidacy will inevitably make him.

Now, he and three friends from law school will open their own firm next month, focusing on appeals. They are dreaming up a name that will not incorporate their last names, “which is what people did when they set up law firms 50 years ago—not now.”

Bergeron “regressed” in his coming out around 2011. “I didn’t know how people would accept me and retreated back into the closet a bit. Over time, it became a progressive coming out again. Frankly, it was exhausting in retrospect.”

Living in the city has helped him be out, Bergeron said. He is single. “I’ve been spending all my time trying to be the best lawyer I can, volunteering all over the place, and now running for office. I’ve always been very career-focused. That’s where I am.”

Does he want to be with someone? Bergeron laughed. “Every weekend my mother asks me when I’m going to find somebody nice. She wants grand-kids. I promise you, you’re not going to pester me more than my mom will. I am not trying to rush into anything. I’m waiting for the right guy to come along, and when he does he will.”

Would he like to get married and have a family? “Eventually that is something I would like. I live by myself. It’s pretty cool. I eat what I want, I have parties at my house when I want. My friends come over to play board games. My friends from law school bring their kids over. They call me Uncle Evy.” To wind down, Bergeron also goes to the gym, and on TV is watching The Handmaid’s Tale and has just finished HBO’s “so good” Years and Years (like many other fans he “audibly gasped” at the end of episode 4).

The LGBTQ history of New Orleans includes the terrible fire at the UpStairs Lounge in 1973, which killed 32 people. The lessons of that tragedy echo down the years, said Bergeron.

“It was not, itself, an act of homophobia, but the aftermath was. The authorities refused to acknowledge the violence against a queer group and refused to give the crime the attention and investigation it needed,” he said. “Further, the sudden shuttering of black queer spaces was just another way to advance the institutional racism that is still so prevalent today. But history repeats itself. There are so many problems plaguing the LGBTQ+ community and communities of color that Louisiana fails to acknowledge.

“Mayor (LaToya) Cantrell has done a good job bringing some of these challenges to light, like the continued murder of transgendered women of color, but we need a statewide focus, because these challenges are not unique to New Orleans. The UpStairs Lounge tragedy should continually remind us to live out loud, because justice depends on it.”

Homophobia still wins votes in the Deep South, Bergeron acknowledged. There are several groups in Louisiana that he sees as hate groups because of how extremely anti-LGBTQ they are. Bergeron also pointed to the 10 Republican senators who last year voted against a bill to outlaw bestiality, concerned it would overturn the state’s ban on sodomy—which has been ruled unconstitutional but remains on Louisiana statute books.

“That is what voters get so angry about,” said Bergeron, “politicians in Baton Rouge getting caught up in semantics or appeasing certain lobby groups with their ridiculous positions, so they don’t send out mailers warning people not to vote for them.”

“There are still a lot of LGBTQ people who live in fear in the Deep South,” added Bergeron, “even in New Orleans.” One night, one gay friend was beaten up by a group of fraternity boys, he recalled. “Remember the ‘It Gets Better’ campaign? Of course, I never believed it at the time. But now I hope that I can be an indirect demonstration to others that it does in fact get better. And I hope I can reach people who are fighting internally with the same thing that I fought with. Even if I can’t be in personal contact with them, I hope my candidacy helps tell them they’re OK.”

Parker, one of the first out mayors of a major city (Houston, 2010-2016), noted that it was a crowded primary that Bergeron was aiming to win.

She estimated the District 98 race would be won with around 3,500 votes. “You can touch 3,500 hands multiple times,” Parker said. “This is a field campaign. Mr. Bergeron can absolutely win it, but he has got to go out and do the work and inspire others to help him. This is an archetypal shoe-leather campaign. You are doing what we call ‘retail politics’: knocking on doors, shaking hands, having conversations. That is how this race will be won. It’s absolutely winnable, the same way Danica Roem won hers.”

“I’m so excited to get to work for the people of New Orleans,” Bergeron told The Daily Beast. “I’ll do the best I can. I just want to make everyone proud.”

Just as Parker said—and just like his raring-to-go mother and father—now it’s time for Bergeron to put on those walking shoes.

Got a tip? Send it to The Daily Beast here

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.